After working under the great Wakamatsu Koji, Shiraishi Kazuya knows exactly how to achieve his goals.

SHIRAISHI Kazuya is hopeful that new players like Netflix will prove to be a good influence.

With his wealth of experience in television, Shiraishi Kazuya has succeeded in creating films aimed at restoring Japanese cinema’s originality.

When did you decide you wanted to become a film director?

SHIRAISHI Kazuya : When I was in my early 20s. I’ve always liked films. In high school I even joined a film study group, and I knew I wanted to work in film, so I enrolled in a visual arts college in Tokyo. Then I heard of a film workshop where director Wakamatsu Koji taught around twice a year. Wakamatsu was looking for an assistant director, and I stepped forward. At the time, he’d just released Endless Waltz and was mainly making straight-to-video films, like Ashita naki machikado. I’m afraid very little from that period has survived.

What was it like, working under Wakamatsu?

S. K. : It was exciting. I was scolded a lot, but it was fun.

How about you? Are you strict on set?

S. K. : Obviously, we’re all professionals and I want to get the best out of everybody, be they cast or crew. But Japanese cinema has a long history of harassment and bullying. That’s something I’m completely against. So I never raise my voice, even when I’m upset, and try as much as I can to create a happy mood on set.

One of your latest films, Dawn of the Felines (Mesuneko-tachi, 2017), was part of film studio Nikkatsu’s Roman Porno Reboot series. Were you inspired by Wakamatsu?

S. K. : Maybe not directly, because when I worked with him, he wasn’t making soft porno films anymore. However, I learned a lot from him, and was a fan of the old Pink cinema of the 60s, so I guess I was somehow influenced by Wakamatsu.

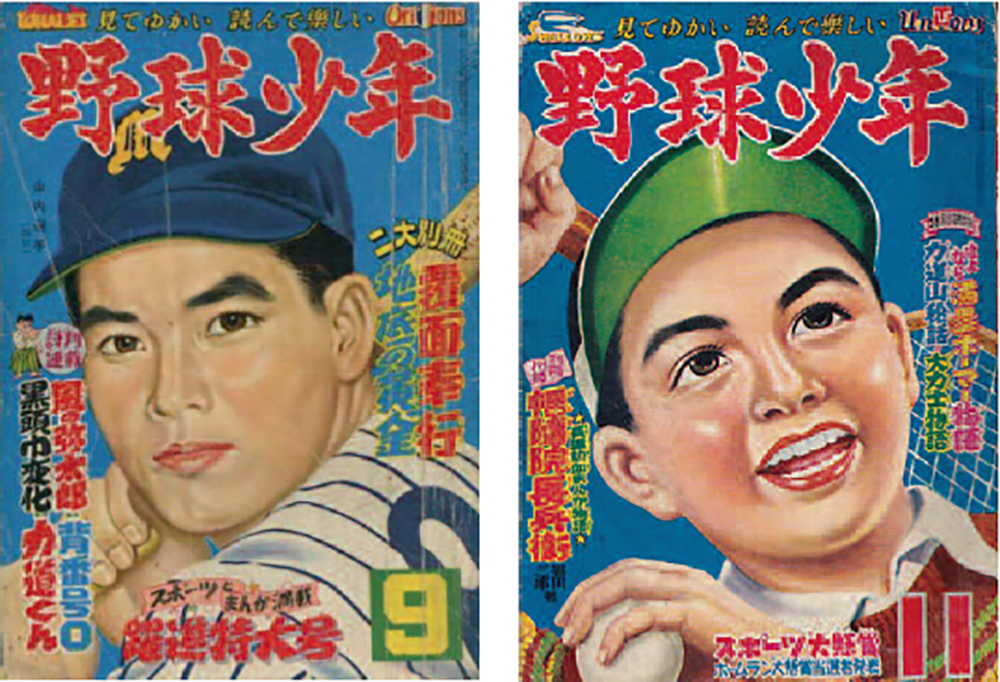

I heard Roman Porno and Pink films are made according to certain rules that only apply to this genre.

S. K. : Traditionally, you’re required to show a sex scene or at least a nude female every ten minutes. These are erotic films, after all. On the other hand, you have a lot of latitude story-wise. The plot doesn’t need to be just a pretext to link one sex scene to the next. Wakamatsu himself used to tackle heavy stuff such as politics and social revolution. In my case, when I made dawn of the Felines, nikkatsu was trying to revive the genre. So on the one hand, I looked back to the past for inspiration, but on the other hand I looked for ways to inject something new and more attuned to the present, like the loneliness of living in a big city in 21st century Japan. It was quite interesting working on this project, and I wouldn’t mind doing another one.

Your debut as a film director was in 2009 with Lost Paradise in Tokyo. Then, until 2016, you mainly worked in television.

S. K. : Yes, it was the only way to make a living (laughs). Generally speaking, it’s easier to find money for a TV project. Lost Paradise was a very small indie film and went unnoticed. After that, I found it difficult to make another film, but I wanted to keep directing, and TV gave me this chance. Apart from the money, it was an opportunity to improve my skills and get noticed.

I guess it’s a different world from cinema?

S. K. : The main difference when shooting a TV drama is that you have to keep your audience entertained – glued to their TV sets – especially now that people have a very short attention span. As soon as the tension decreases, they change channels. In a cinema, you’re given more time to build up your story and develop a certain atmosphere. unless people really hate a film, they don’t walk out after ten minutes. Production- wise, working on a feature film and a TV drama is not as different as before. Many broadcasters are now producing their own films – particularly in Japan – and film stories and style have changed accordingly. As for me, now that I’m able to focus on feature films, I’ve made a conscious decision to produce works that are as far as possible from that trend.

You’re mainly known for your real-life crime films. Why are you so attracted to these stories?

S. K. : Because I like to dig into these people’s lives and motivations to see why they acted in a certain way. Whatever we do, good or bad, there are always moments when we have to make a decision. I put myself in these people’s shoes, and try to imagine why they went down that path instead of another. All my films try to answer the same question: what does it mean to be human? In this respect, crime stories are, at least for me, the best medium to explore this issue.

This said, your latest crime film is not based on a true story, but on Yuzuki Yuko’s novel.

S. K. : Yes, this novel was inspired by the Toei studio’s great film series of the 70s, like Battle without Honor and Humanity, which, like the book, takes place in Hiroshima. nobody had made something like that for many years. When Toei decided to revive the genre, they looked for someone who could approach the story with a more contemporary sensibility. That’s how I was offered the film. I must confess that at first I wasn’t sure I could handle it. But I’ve always liked the 1970s-80’s period, when all these stories take place, so I accepted the challenge.

Generally speaking, how do you choose your projects? What inspires you?

S. K. : Other people’s films are always an important source of inspiration – even works that are very different from what I usually do, like disney animation or Marvel movies. I also get ideas from talking to people. And then, of course, watching the news – any kind, not only crime news; like political scandals or the next elections.

Is humanity really as bad, cruel and violent as you depict in your films?

S. K. : no, not at all (laughs)! I mean, there are plenty of bad people around. But the interesting thing is, even a murderer can go home after committing a crime and play with his children, or be nice to his girlfriend. There’s more than one side to each of us, and I always try to portray my characters as complex people. Even the bad guys can have a funny or tender side. nobody is completely good or bad. Life is definitely more complicated.

Birds without Names is rather different from the other films you have made so far. What place does it occupy in your filmography?

S. K. : For a long time, I’d been looking for a suitable love story, i.e. not your typical romance, when I read numata Mahokaru’s novel. I was struck by the fact that the two protagonists are rather stupid, unlikable people. And I thought, that’s exactly the kind of story I like (laughs)!

Indeed, it’s a very original take on a love story. But weren’t you afraid that such detestable people would derail your film?

S. K. : That was my major worry. It’s really difficult to warm to the protagonists at first. As I said, doing something like this on TV would be suicidal, because viewers change channels so quickly the moment they don’t like something. However,mine was a feature film, and I gambled on the fact that if the audience could bear to watch this unsavoury couple for the first 20 minutes or so, the film would be safe, as the story gradually reveals their more positive side.

Your films have been shown abroad too. How would you compare the way people react to them in Japan and other countries?

S. K. : I’d say people abroad are more receptive to the comic, funny side of humanity. In Japan, I often find it harder to make people laugh. Sometimes we Japanese are too serious. On the other hand, the author of Birds without names, numata, is the daughter of a Buddhist priest who took holy orders herself, and the novel’s ending is based on the principle of the endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. I guess a Japanese audience is more attuned to these ideas, while for people in the West it’s probably harder to see the connection with Buddhism.

Do you think the Japanese film industry has changed since you started?

S. K. : no, I don’t think so. In a sense it’s going backwards. For example, in Europe I’ve noticed that many older people regularly go to the cinema. In Japan it used to be the same, but now most studios only make films for a certain age group – teenagers and people in their 20s and 30s. I wish Japanese films appealed to a wider audience, like in the past. Also, many of the films being produced now are quite shallow. They only aim to entertain. It’s rare to see thought-provoking works that dare to go deeper and explore the human condition. I believe you should accomplish both. Otherwise film culture becomes cheapened. Add to this the fact that the government is not very interested in supporting our films, and the situation is not particularly good. On the upside, over the last year, total earnings have gone up compared to the recent past, so I’m not totally pessimistic. I’m also hopeful about the positive influence that new players like netflix can have on the industry as a whole.

INTERVIEW BY J. D.