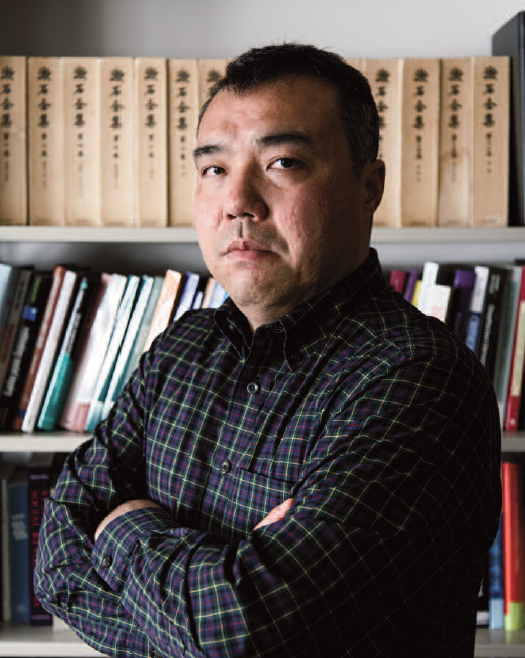

He has lived in Japan for over 40 years, and every week this Briton puts forward his views on his adopted country.

On a beautiful sunny afternoon in Tokyo we met up in NHK’s offices, close to the former Olympic stadium currently being demolished to make way for new facilities where most of the events of the 2020 Olympic Games will take place. Peter Barakan, presenter of the show Japanology, is waiting for us so he can share the story of his experiences in Japan that began over 40 years ago. This man, who has most notably helped build bridges between Europe and Japan in the field music, has avoided the phenomenon of becoming one of those foreigners who is disdainfully described as being “more Japanese than the Japanese”. He has maintained a critical distance from his country of adoption, allowing him to have a balanced view on the years he has spent there.

When and why you first came to Japan such a long time ago?

Peter Barakan: It’s 40 years ago now. It’s a strange story. The short answer is that a music publishing company was advertising for an Englishman to work in Tokyo, and I saw the ad because I was working in a record shop in London. The longer story goes back to the fact that I studied Japanese in college, and that is the weird part because there isn’t a very good reason why I did it. I always get asked this and I suppose to start with I have always liked languages. I did Latin and Greek in school for seven years and enjoyed them. I mean they are dead languages — they are useless except for the fact that they help you understand your own language, not only English, but I think most European languages. And I think I liked the puzzle aspect, especially of ancient Greek; it was like solving a puzzle sometimes. When I was trying to decide what to do after I finished school at the age of 17, I did not want to go out and work. Back in those days in England income tax was, I think, a minimum of 30% and, on other hand, university education was free. It isn’t any more, I’m sure you know. So I didn’t have to feel guilty towards my parents for going to university for the wrong reasons, and I decided, “okay I’ll do some kind of a language”. I couldn’t make up my mind, there wasn’t one particular thing I wanted to do. I thought that if I was going to study a language then I did not want to do a regular European language, because you might as well just go and live in the country and learn it, so I thought I’d do something that was a bit more of a challenge. I was having conversations with friends and parents and everything, and saying things like, “Oh no, not this one, oh no, not that one”, and one time Japanese came up in the conversation, and for no good reason I said “Hmm, that’s interesting”. It’s funny because I was speaking to somebody earlier today who is in America and started studying it for almost the same reason. It’s just “Oh, that’s interesting”. So I went to college and studied Japanese, and I knew nothing about the country and nothing about the language. Looking back on it, it seems like a really strange thing to do, but you know sometimes when you’re 17 or 18 you do strange things. Then, after I got out of college, I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life. I didn’t particularly intend on coming to Japan at the time, and music was the most important thing to me, so I wanted to work in something connected to music. The first job that came up was working in a record shop, so I did that for 9 months, and then this opportunity came up to go to Tokyo. It came up pretty suddenly, out of the blue. And when they actually called me up to tell me “Yes, we want you to come”, it was even more sudden because they wanted me to be here 10 days after they called. So I had to get rid of all my stuff, or leave it at my mother’s house.

Was that difficult for you?

P. B. : It all happened so quickly that no, it wasn’t difficult. If I wasn’t interested then I would not have applied in the first place. I had no idea how long I’d end up staying, I didn’t even think about it. I was still only 22 years old at the time, so it was like an adventure, and 40 years later — here I am!

Do you remember your first impression of being in Tokyo?

P. B. : The very first impression was shock because I arrived on July 1st, which is the middle of the rainy season. It was pouring with rain. The sky was dark grey and I had never seen rain like that in my life, because in Europe, at least in those days anyway, you just didn’t get rain like that.

Even in England?

P. B. : There is a lot of rain in England but not heavy, you know, real monsoon type rain. So in those days you didn’t have the covered walkway from the terminal to the plane; you had to go down some steps and get on a bus. This was still in the days of Haneda, long before they built Narita. I think I got soaked in about a second flat! It was a bit of a shock and the humidity, of course, was very, very high. But, okay, so somebody came to take me to the office. Some of my first impressions were smells, because I think most countries have their own smells, and I remember going out for lunch the first day I arrived. I was taken to a soba restaurant and I remember the smell of shoyu mixed with dashi. It’s a very distinctive smell and I had never smelled anything like that in England before. It wasn’t unpleasant, but it was just very strong. I remember feeling a little overpowered for the first time, for a little while. Other cooking smells that I did not find so pleasant were, for example, daikon. I’ve never liked the smell of daikon, in particular daikon oroshi — I have to get away from that. And oshinko as well, Japanese pickles. The smell of that is not something I like. I can remember when you go into a department store, from the front entrance there are steps usually going down to the basement where they have all the food, and immediately you can smell the pickles, and I thought “Urrgh, I have got to get away from this”. So there were little kinds of small culture shocks. Perhaps not culture shocks, but small kinds of things.

Smell shocks?

P. B. : Yeah, smell shocks! But in general, it was all a big adventure. Everything was new, I mean I had studied the language, but it was very much a language course and we didn’t really learn a lot about Japanese culture. We had read a book — I think it was in the second year — called “Nihonjin no ikikata”. There was a little bit in it about Japanese culture. I had read a little bit in an optional course in the third and fourth year when I did a little bit of sociology, but reading it in a book and experiencing it first hand is a totally different thing. So it was all a big adventure to begin with. And it was interesting because I didn’t have too much knowledge. I also didn’t have many preconceptions, and that made it much easier to adapt. If you have studied a lot and you do have preconceptions, maybe you don’t adapt so easily. Maybe.

Perhaps it’s more of a shock?

P. B. : Yeah. I remember though — this is in the summer of 1974, it was 40 years ago — it must have been probably the second week I was here, and I had one friend who lived here, a Japanese friend when I first came here, and I remember his sister took me out to Shinjuku. It was a weekend, it must have been a Sunday because it was hokosha tengoku, when they close the roads down, and it must have been Shinjuku doori on a Sunday afternoon, and the sheer number of people in the street, that was a shock. Because, I think I knew vaguely that Tokyo was an enormous city with, you know, an incredible population, but to see literally thousands and thousands of people filling the street — it was a big street in Shinjuku — I re-member that being a shock. I also remember getting lost in Shinjuku Station numerous times during my first year here. The idea of a railway station that big — there’s nothing like that in London — with all the different lines running through it. Oh, and another thing… you’re are going to have to stop me because…

No, no it is very interesting,

P. B. : Ticket machines! In 1974, I don’t know about Paris, but in London there were some very, very primitive ticket machines in the stations. You had to put in the exact money, and almost nobody used them. Everybody went to the little ticket window and you queued up to get your ticket to go on the train, unless you had a pass. In Japan they had these rows of machines and you could put in whatever money and the change came out! It was so efficient and I was just blown away by this because probably… I’d imagine that England was not particularly backward, so I’m assuming that probably most of Europe was the same. And the banks, of course, the ATM machines. I think that maybe they had them, but I had never used one, but I came to Japan and they had them in all the banks in the mid 70s. I mean, I felt scared, I was intimidated by them! I didn’t know how to use them, and for several years I didn’t use them. I’d go to the counter and get my money from the cashier. So in all kinds of ways it was very different.

But you liked it?

P. B. : To begin with, I think I liked everything because it was all new and it was all a new experience. But after about a year, after I got used to it, there were a lot of things that were frustrating as well, and for a little while I think the frustration got the better of me, and for a while I think I toyed with the idea of leaving. In my second year I remember I wrote a letter to my mother explaining the feelings I had. And she said “Hmm, hmm, I think I understand what you’re saying, but you should remember that it’s not Japan that’s changed but you”.

You were getting older?

P. B. : It was funny, because reading that I felt “Hmm”, and as soon as I read that, all the frustration flowed away and I became a lot more neutral about it.

So you accepted it?

P. B. : I mean, I still get frustrated with aspects of Tokyo in particular, and perhaps Japan in general. Obviously you grow up in a completely different society, and I think childhood experiences count for an awful lot in life. I don’t think of myself as British so much, but I do think of myself very much as a Londoner though. And I still have a lot of London in me, and I suppose I still have some kind of a British mentality as well. I understand Japan, of course, and I like it in a lot of ways, but there are aspects of it that I still don’t really feel at home with. You know, some of the popular culture.

This experience of bringing people together and your knowledge of Japanese culture and Japanese society, is this something that you use now in your work on Japanology?

P. B. :Definitely, on the Japanology programme, yes. Because I think that most people who watch Japanology have some kind of interest in Japan, whether that interest comes from an interest in traditional culture, or from manga, or whatever. So they know something about it, but the chances are that they don’t know very much unless they have lived here or something. I always feel that my job is to make the material much more easily assimilated by the average non-Japanese viewer of the programme. So obviously the people who are creating the shows, the NHK directors as they call them, or producers as you would probably call them, most of them are not English speakers. They only speak Japanese, and obviously they have only ever lived in Japan, so their approach to creating the material is very Japanese. Very often when they give me a script I will point out that “Ok, you want me to ask this, but this question, or what I am trying to get at here, is something that only Japanese people would understand. If we want to get this across to the foreign viewers then we have to say something different, so how about if we do it this way?” A lot of that happens in the show, and I think that if you want to be effective in creating television about Japan for a foreign audience then you have to have that element in there. Somebody has to translate the ideas sometimes. We have been doing this show for… it has changed format twice now. The original weekend Japanology programme started in 2003, so we have been going for twelve years now.

And until now it has been a weekly show?

P. B. : It’s a weekly programme. I think they produce 40 shows a year. Which means, I think, that the last week in every month is a repeat of something that we did before.

About the Japanology programme, what aspects of Japanese culture and Japanese daily life do you think people outside Japan want to see?

P. B. : That is a really good question. I don’t really have the answer to that. Quite a lot of people write to me through Facebook these days, and occasionally people come up with ideas for specific things they want us to cover on Japanology. I had somebody that came up the other day with — what was it? — some kind of glassware I think. I can’t quite remember, but if I go back and look on my computer it will be there. But it was something really quite obscure, a particular type of Japanese glass production. But he said “you must do a show on this”. Somebody else wanted us to do something on — was it swords? — I think Japanese swords. And you know, I think over the years a lot of people have started to pick up on Japanology — over the last 2 to 3 years. And it has been going much longer. I’m sure very few people were aware of the original programme. So we actually have covered a lot of these themes in the past, and we probably need to do them again — and I’m sure we will get around to doing them again.

When you’re working on Japanology, are you working mostly in Tokyo, or do you go outside Tokyo to try to find…?

P. B. : Well we go outside Tokyo on location quite often, but almost always it’s a day-trip. We go early in the morning and come back in the evening. Once in a while, if it is summer and it is quite far, then I might spend one night, but I never really have time to explore and spend time, and in a lot of ways I think the real Japan is outside Tokyo. I mean, Tokyo is a bit like New York in America. Sometimes it’s almost like a different country.

So why didn’t you call the programme “Tokyology” rather than “Japanology”?!

P. B. : (Laughs) Well, actually there is another programme called Tokyo Eye that I have seen. But no, we do cover other parts of Japan, but in order to really spend time there I would have to give up all of my other work to go and spend, like, a week in Shimane or something. Unfortunately it doesn’t happen, but even when you go for a day you notice the difference. The people — when you are dealing with people or just coming into contact with the local people — it’s so different from Tokyo. I mean, everybody is just so nice! I think anywhere in the world you go, when you go into the countryside people are much nicer. So it is not something that applies just to Japan, but it is something you notice. So when we went to places like, I don’t know, Akita for example, — places that are fairly far out in the countryside — it’s like you’re dealing with… not a different race of people, but a different type of people.

I’d like to speak about music because it is your passion. Music and Japanology. You have a programme and this programme is for a Japanese audience. But imagine, for example, that you have a music programme aimed at foreigners, to introduce Japanese music to them.

P. B. : I would love to do it.

How would you do it?

P. B. : Well, in addition to the programme I do on NHK I also have a programme on Inter FM. And when Inter FM started in 1996 I actually had a show then and it was all in English, so a lot of the English-speaking people in Tokyo used to listen to the programme.

But you are talking about a worldwide programme?

Yes, of course.

P. B. : Japan is the only developed country which doesn’t have internet radio broadcasting outside the country, and this is just so stupid. And it’s because the record companies in this country have this very blinkered world view, I suppose. They have this idea that “This is our music, you can’t have it”. You know, if they put it on the internet they think somebody is going to copy it. Come on guys, where have you been living for the last 20 years, you know?

But how to change it?

P. B. : And that’s the problem. Japan has always been, what’s the word… um, sensitive to foreign, outside pressure. It’s very difficult to put pressure on people from inside the country. You can make a lot of noise and complain like I do, but nobody takes any notice. I have been thinking a lot recently about the 1960s pirate radio in Europe and it’s very interesting. They did something that was not actually illegal, but close to it — and it was so popular and so many millions of people listened to it that, indirectly, they were able to change things. It took maybe a couple of decades to really change things, but in the 1980s the media picture in Europe really changed dramatically. I think it took something like that to wake people up. Perhaps it needs something like that in Japan to wake people up, to make them change.

Have you got some ideas? Maybe take a boat out around Japan?

P. B. : (Laughs) Well, we don’t even have to do that now. You can go on the internet through a server in the UK, or in America, or somewhere else, and you can actually circumvent the law and do internet radio like that. I am actually looking into the possibility of doing something like that because it would be interesting as there are so many people coming to Japan in six years’ time for the Olympics, and the number of tourists who are coming anyway, I mean, it’s on the rise now, increasing. People are interested, they do want to know. Japanology is great. There is a lot of other stuff that needs to be got out that Japanology can’t do because it is just one show for 30 minutes a week, and it would be good to have a way to do that. As long as you’re not doing it with music, you could do it anyway. The only problem is that if you are playing music, copyrighted music, then you have to circumvent the law. For just regular information about Japan you could do it over the internet with podcasts, or whatever. I’m actually looking at all kinds of possibilities of doing something like that.

Interview by Odaira Namihei

Photo: Jérémie Souteyrat