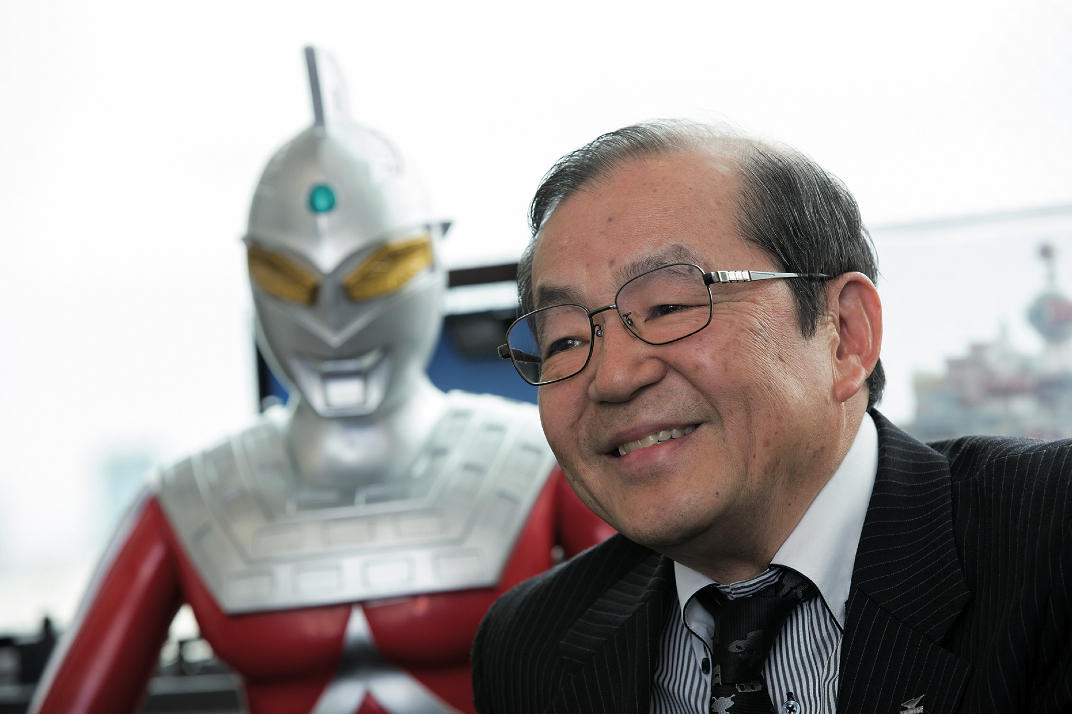

Writer Takahashi Genichiro on writing, politics and the charms of horse racing.

Writer Takahashi Genichiro on writing, politics and the charms of horse racing.

Takahashi Genichiro is one of the most important all-around Japanese writers of the last 30 years and one of the pioneers of the postmodern novel in this country. From fiction to essay, from literary criticism to sports writing and political commentary, the 62-year-old Takahashi mixes a strong moral stance with an extraordinary imagination which constantly challenges the reader to abandon rationality in order to explore the worlds he creates. Takahashi’s life is almost as picaresque as his stories. As a student radical, he was arrested and his experience in prison left him incapable of expressing himself with words for many years.

When did you decide you wanted to be a writer?

Since when I was in high school, although my life took several detours before I actually decided to give it a serious try. I belong to the “1968 generation” and I was directly involved in the students protests. Actually, in Japan the demonstrations reached their peak in 1969, i.e. the very year I entered university. After being arrested and expelled from school, I worked as a manual laborer for ten years. You see all the roads in this area? I worked on all of them (laughs). And then, when I hit my 30s, I suddenly remembered my old dream.

You had been involved in the student protests even before entering university, right?

Yes, the radical movement even swept through my high school in Osaka. We were against the Vietnam War and shared the same revolutionary ideals with the other movements in Europe and America but we were also dealing with some typically Japanese issues like the US-Japan Security Treaty and the American occupation of Okinawa. However, apart from any specific problems, I think there was a lot of raw anger. We were fundamentally frustrated toward society and the education system and we reached a point when we felt we had to do something.

In the 1950s and ‘60s people in Japan were often in the streets protesting. Then, in the ‘70s, they suddenly stopped and nothing happened until recently. Why was that?

There was a strong feeling of disappointment throughout the student movement. This led, in 1971, to the birth of the Japanese Red Army that conducted a series of terrorist actions and further distanced society from left-wing politics. At the same time the quality of life got better and better through the ‘70s and as you know, when people feel well-fed and satisfied they stop complaining.

You were arrested during the demonstrations. How long did you spend in prison?

Actually I was arrested three times. The first time I spent three weeks, the second one week, and the third time they kept me in for ten months.

Was it at that time that you began to suffer from aphasia?

Yes. You have to understand that only one visitor a day was admitted and they could stay only five minutes. On top of that we had no privacy, as a guard was always present. In those conditions I gradually lost my ability to talk, even when my girlfriend was visiting. It took longer and longer to put my thoughts into speech and even when I came out I had trouble using everyday language. This experience left a psychological scar that in a sense hasn’t healed to this day. Eventually I figured that if I couldn’t speak properly, I could at least express myself in writing, so you could say this was a blessing in disguise.

So in a sense even your writing style was affected by your problem.

Yes, you can definitely say so.

Is it true that “Sayonara, Gangsters” is partly autobiographical?

Certainly you can find many references to my life experiences but everything is told in a roundabout way. This is also due to the problems I still had in expressing myself. In other words, I had to find a way to say what didn’t come out naturally. So I came upwith this particular style. The end result is that all the autobiographical parts are camouflaged and made invisible by the way I told them.

When critics and reviewers talk about you, they often use such terms as post-modern, meta-fiction and metanovel. Do you agree with them?

I think if I was a critic I would do the same, as it is true that I was influenced by a number of post-modern writers. At the same time I’d like to point out that I liked them simply as writers, without really consciously thinking I want to write meta-fiction or something like that. Also, post-modernism can be difficult to define. For example, my favorite writer is Italo Calvino. Many of his books can be defined as meta-fiction but he flirted with so many styles and there are so many sides to his work. I don’t think anybody would call him a postmodern novelist.

How about you? How would you define yourself as a writer?

I wish I could write like Calvino. I particularly like his American lectures, where he compares lightness and heaviness, and states that his lifelong work has been a slow process of subtraction in order to make his stories and language lighter. In my books I aim at the same goal. Then it’s up to the reader to decide whether I’ve been successful or not (laughs). Apart from that, I have always loved modern Japanese poetry and I consider my creative roots as being poetry rather than novels. In Japan, the mainstream novel is dominated by realism, whereas the world of poetry is high modern. For many years I have read the works of such poets as Tamura Ryuichi and Yoshimatsu Gozo who pursue their style of language very self-consciously.

In the past modernism wasn’t very popular in Japan, was it?

That’s right. As I said, Japanese literary tradition – let’s say mainstream literature – was represented by the socalled “I novel” and naturalism on one side (think about Natsume Soseki) and the political novel on the other. In both these trends, content was valued much morethan form and style. Now, according to this point of view, modernism was light on content and rather out of touch with reality, therefore not worth taking seriously. Even now things have hardly changed in this respect.

“Sayonara, Gangsters”, your debut novel, was published in 1982. Do you think that being a writer in Japan now is easier or harder than 30 years ago?

It depends. For example, when my first novel came out there was a rigid distinction between literature, comics and movies etc. If you were a novelist you were supposed to work in a certain way. There were also technological limitations and budget restraints. Once I asked my publisher to include a flexi-disc in my book because I wanted to present the last chapter in that form but I was told it was too expensive. But now the multimedia approach has become common and people mix genres all the time. Already in 1984, my second novel “Over the Rainbow” contained photos and other typographical innovations. So you can say writers have gained considerable creative freedom and with the advent of the Internet, blogs, e-books and mobile phones it’s getting more and more difficult to define a novel. At the same time though, so many people write now that even a successful debut is no guarantee of a successful career. Publishers have grown impatient; they don’t have the time or the strength to nurture new talents and the competition is so great that at the first flop they dump you for the next big thing.

What do you think is Japan’s position in international literature?

Japanese literature is a rather peculiar, sometimes even strange entity. First of all, compared to other countries, Japanese society has reached the post-industrial stage in record time. We don’t have new frontiers to explore. Our society seems to have reached its limits and this sense of crisis – what I call the end of capitalism – comes out in many novels. Another thing we can say about Japanese writers is that they are a little crazier than in other countries (laughs). They seem to know no bounds and are always experimenting and pushing the envelope. By comparison, Western writers seem to be more conservative.

Has your writing been affected by the disasters of March 2011?

Definitely. For many years I rather consciously avoided writing explicitly about political and social issues. Then in April 2011 (i.e. only one month after the disaster) the Asahi Shimbun asked me to write a monthly opinion column. I took it as a chance to contribute my thoughts on the subject. There was a period soon after the earthquake when most people seemed to pause and think before expressing their opinion. Instead I felt it was important to speak soon, even at the risk of saying something wrong and being criticized. I’ve kept writing for the last two years and now I can say it’s been stressful and I’m tired. I’ve also realized I’m not really fit to write this stuff.

What are in your opinion the most urgent issues Japanese society needs to address?

The 2011 disasters happened only two years ago, yet people seem to have already forgotten about it. Soon after the disaster, it became clear how dangerous nuclear energy was and how the whole system was based on the corrupted alliance between TEPCO and the government. For the first time in about 40 years people made their voice heard through mass demonstrations. In other words, it seemed that Japanese society was finally ready to change for good. Yet in December the Liberal Democratic Party – i.e. the main culprits responsible for the disaster – won a landslide electoral victory and now they are talking about restarting the nuclear plants. I kind of expected this but I was really surprised by how conservative Japanese society is; how much people dislike change. It seems as if nothing really happened in these two years.

Can literature change society?

This is a tough one to answer. Taken as straight political propaganda I don’t think that books can affect change. Nevertheless, a writer can express what people feel but can’t put into words. You can show that other lifestyles are possible. In this sense a work of fiction can be a very political thing.

Do you think contemporary writers are doing enough in this respect?

It’s a generation thing. Older people like Oe Kenzaburo belong to a generation that was politically involved and have kept expressing their ideas in a clear and strong way. On the other side you have those writers who are now in their 40s and 50s, who experienced the trauma of the student movement’s defeat. They have largely kept away from these issues. But the younger generation, i.e. people who are in their 20s and early 30s, have grown in a very different society where good jobs are hard to find and the young are uncertain about their future. I think these writers are angrier and show their concern in their stories.

Between 1990 and 1997 you didn’t write any novels, did you?

That’s true. I went into a slump, or maybe I should say I got tired of writing fiction – especially the kind of post-modern novels I had written in the ‘80s. I increasingly felt I was wasting my time. So I decided to take a break, which became a seven-year-long hiatus in which I mainly went to the horse races (laughs).

I heard about your interest in horse racing. Is it really so interesting?

It’s a lot of fun but only if you like gambling. That’s what first attracted me to the races. But then I got interested in the whole horse-breeding culture that was born in England, like the way the breeder, almost like a god, shapes and controls a horse lineage in order to produce a thoroughbred. This is something that only an aristocrat with a lot of money and time on his hands could achieve. It’s an extremely fascinating world but once it sucks you in, it’s difficult to quit. Luckily I did it. After all, for a writer, life itself is like gambling.

Interview by Gianni Simone

Photo: Jérémie Souteyrat