In 2025, NHK chose to dedicate its annual saga to the man who promoted the flourishing of books in the 18th century.

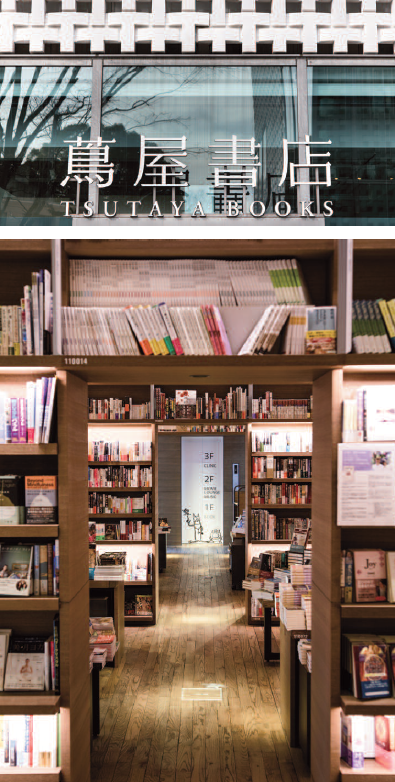

Like every year since 1963, NHK is broadcasting a new taiga drama, its prestigious year-long historical drama series. This year’s production, Berabo (English title, Unbound) is based on the life of Tsutaya Juzaburo (1750-1797), the “media king of Edo,” who introduced the world to such ukiyo-e artists as Katsushika Hokusai and Kitagawa Utamaro, and authors Santo Kyoden, Takizawa Bakin, and Jippensha Ikku.

Tsutaya Juzaburo (also known as Tsutaju) was born to a poor commoner in Yoshiwara, the pleasure district located on the outskirts of Edo. He was separated from his parents at a young age and adopted by a teahouse owner. He started out as a rental bookstore owner and later began his book editing and publishing business.

In the free atmosphere created by Tanuma Okitsugu, a senior counselor to the shogun, Edo culture flourished. Tsutaju had many connections with cultural figures and produced a succession of hit books with lavish illustrations in the form of kibyoshibon (literally “yellow-covered books”). These picture books are considered to be Japan’s first purely adult comic books. Known for their satirical view of and commentary on flaws in contemporary society, they focused primarily on urban culture, with most early works being about Yoshiwara.

At the age of 33, he set up shop in Nihonbashi and rose to become “the publishing king of Edo.” However, times changed, Tanuma Okitsugu fell from grace, and Matsudaira Sadanobu, who rose to power in his place, brought Tsutaju’s political satire into question. Although he was subjected to relentless oppression and even had half his property confiscated, Tsutaju continued to show his anti-authoritarian stance.

I had a chance to talk to screenwriter Morishita Yoshiko and NHK producer Fujinami Hideki about Berabo and Tsutaju.

I believe this is the first time a taiga drama has been set in the late 18th century. Why did you choose that particular era?

Fujinami: The late 18th century was a peaceful time when the focus was on the economy and social issues. In this respect, we thought it was very similar to modern Japan, and that’s the reason we chose that era. During those years, social status was determined from birth. If you were born into a farmer or merchant family, you were bound to be a farmer or merchant all your life. Also, though there were no wars, people felt a strong threat coming from overseas. All those elements reminded me of contemporary Japan. Up until now, many historical dramas have been set in other periods, but I believe that a story from that era might be able to resonate with people today. That’s why we chose it.

Morishita-san, compared to other historical dramas, this story does not feature any battles, is not about political intrigue, and nobody dies dramatically. In a sense, it is just a story about the life of a publisher and bookseller. Why do you find this story appealing?

Morishita: This is the story of a man who, to put it bluntly, was born into the lower strata of society, somewhat outside the conventional framework, and yet managed to rise to the top. What makes this story so compelling is that Tsutaju came from that place but became the darling of his time.

What do you find particularly interesting in Tsutaju’s life?

Morishita: First of all, the books that Tsutaju published are extremely interesting. That goes for both the kibyoshi and Nishiki-e [multi-colored woodblock prints] books. I’m not only talking about their content. For example, with Yoshiwara Saiken [a guidebook to the Yoshiwara pleasure quarters of Edo whose contents included a rough map of the pleasure quarters, the names of brothels and prostitutes, their fees, a list of teahouses and inns, and names of geisha] he played around with the format itself. I used to be an editor myself, and I think his editing sense – the way he presents the information and his nose for what readers want – is outstanding. His talent, likeability, and communication skills are the reasons why he became the best of his time. Even now, after all these years, his works haven’t aged at all.

This is your second time writing a taiga drama. What is, for you, the appeal of historical dramas, and how would you compare the two experiences?

Morishita: As a writer, the taiga drama’s very format makes it a wonderfully challenging genre. It runs for 48 weeks, each episode being 45 minutes long, which can be tough for a writer. However, that’s also its great strength. The fact that it’s so long means you can express the complex aspects of a person’s life and character and explain why they became that way. The biggest attraction for me is that you can depict their life in depth rather than just hinting at it with a few strokes. That can also be said about the historical context.

Of course, writing such long stories is always difficult but the two taiga dramas I’ve been involved with have posed radically different challenges. When I wrote Naotora: The Lady Warlord (2017), I was given a blank slate: there was no timeline, and the lack of documents on which to base the story made it a challenge. However, this time I have access to an overwhelming amount of materials. Many documents have survived, and since Tsutaju worked in the publishing industry, we have access to many of his works. Then, when it comes to the writers and artists and other people around him, the amount of materials is just enormous. So now I’m drowning in a sea of materials, and the big challenge is to figure out how to fit in all this stuff in the story.

The drama’s English title is Unbound. However, the original Japanese title is Berabo. Why is that? And what does Berabo mean?

Fujinami: Morishita-san and I considered several titles, and in the beginning we thought of Tsutaju’s Glorious Dream Story. However, it was too long and didn’t feel right. Then, Morishita-san came up with the word Berabo. Originally, this word meant “idiot” or “fool,” but later came to express something unconventional or out of the ordinary, and we agreed that this word captured the spirit of a person like Tsutaju, whose life and deeds exceed our imagination. It’s a very Japanese word and it looks good, but we added Tsutaju’s Glorious Dream Story as a subtitle.

Morishita: Yes, that’s right. As Fujinami-san said, the word berabo started out as “big idiot” but it gradually came to mean something out of the ordinary, unpredictable. As you know, the meaning of words changes over time. That’s very Tsutaju-like. He went from being an eccentric in Yoshiwara, known for his outrageous actions, to becoming a star of the era.

Fujinami: On the other hand, it was NHK’s overseas development team that came up with the title Unbound. Again, we wanted something simple that would be easily understood by an international audience and give a clear idea of the story. I find this title stands for someone not being bound by anything who rises above his status; it gives the idea of an orphan who was born poor, had no money, and then rose to stardom after overcoming many obstacles.

Morishita-san, how did you approach the protagonist? How did you portray his personality?

Morishita: Everything Tsutaju left behind is cheerful and stylish. He had a great sense of humor, business sense and acumen. Rather than focusing on his success story, I wanted to portray his humanity and how he enriched the people around him. An important clue to his character is his gravestone, which is inscribed with the words “He lived like Tao Zhu Gong.” Tao Zhu Gong, also known as Fan Li, was a Chinese politician and military strategist who was famous enough to appear in the Records of the Grand Historian (c. 91 BCE) and later became a merchant and brought wealth to the places he moved to. In other words, Tsutaju was not only successful in business, but was also known as someone who enriched those around him, just like Tao Zhu Gong.

Another thing is that one of the best-selling Edo authors he supported, Takizawa Bakin, said something along the lines of, “Tsutaju was liked by people and that’s what got him through.” Takizawa Bakin was said to have a pretty bad personality, so I find it remarkable that Tsutaju was admired even by such a man.

Fujinami-san, what do you like about Tsutaju?

Fujinami: When I was talking with Morishita-san about what kind of person Tsutaju was, she said he was a man of determination and responsibility. I think that’s very true. It’s hard to take responsibility for what you say and do. It’s wonderful to be born with that quality; someone who can say, “If someone has to do it, I’ll do it.” That’s the true charm of this character. Even if he does not bring about big changes himself, he is a sort of trailblazer, and people follow him. When he started producing books and ukiyo-e, the people he championed and the works he created with them blossomed as a culture that survived his death and was even recognized overseas, leading to what is called Japonism.

Yokohama Ryusei plays Tsutaju in the series, and his performance is also very like that. How can I put it? He has a very stoic side, or rather, the sort of charm that attracts people.

Tsutaju lived in Yoshiwara until he was about 20 years old. What was his relationship with the pleasure district like?

Morishita: Tsutaju was probably born in Yoshiwara and grew up there after losing his parents. When presenting people who have lived through harsh circumstances, we tend to portray them as characters driven by a desire for revenge. However, Tsutaju maintains a positive attitude. When he sees the prostitutes, who have been sold by their parents, he realizes that he is not the only one suffering. More importantly, he feels that the people of Yoshiwara have given him life.

As for Yoshiwara, it may be a complicated and controversial place, but it’s also Tsutaju’s loving hometown. It is thanks to the pleasure district that he is able to grow up and make a living, and when he is given a chance, he becomes a sort of PR representative for Yoshiwara. It’s hard to think that he was driven by hatred or wanted to abandon his hometown. On the contrary, I believe he loved it, flaws and all, and the women who worked there became his elder sisters in a sense. That’s why rather than a person who holds grudges against others, I decided to portray him as a person who acts for the people around him.

When portraying Yoshiwara, it’s important to remember that each and every character there is a real person, with their good and bad points. We have to ask ourselves what choices those people were allowed to make, and how they lived. You must be careful to portray both the light and the shadows.

Fujinami-san, what is the most difficult thing about creating a story like this?

Fujinami: The story is set in a time that I’ve never done before. It’s neither the Warring States period nor the end of the Edo period. Its protagonist is also a publisher, which is very unusual. Moreover, Tsutaju left behind many famous ukiyo-e prints by Sharaku and Hokusai and literary works by the likes of Santo Kyoden. However, I don’t want to make it seem like an elitist work about high culture. I would like to make it easy to consume and attract as many viewers as possible. Although I don’t know if I’ve managed to do that (laughs)

Yoshiwara is often seen as a narrow, two-dimensional world, a world that’s in many respects far removed from us. But I want to present a more balanced portrait. Watching this drama should be like when you open the lid of your lunch box, and you think you know what to expect, but you find a surprise. I’m trying to defy people’s expectations.

I heard this is the first time that an intimacy coordinator was appointed to a taiga drama.

Fujinami: In depicting Yoshiwara, I wanted to express both the glamorous and dark sides of life. I discussed the matter with Morishita-san and director Ohara and thought that since we were going to feature Yoshiwara’s prostitutes and their relationships, we had to let the staff and actors understand what we were doing. The literacy level and ethical awareness in the world of television production have much improved lately, so it is very important not only to know what kind of program to make but also how to make it. As a producer, it’s my duty to properly set the working conditions, including creating an environment in which the staff and all the actors, not just the main actors but also every extra, feels included and agrees with our approach. That’s why I introduced the intimacy coordinator, who is a person who, when there is nudity or sexual depictions, is there to ensure that the actors can perform with peace of mind and physical safety, while at the same time realizing the director’s vision to the fullest extent. I had already used such a person in a previous production and heard very positive feedback from both the staff and the cast. So I asked the same person to help us and introduced it for the first time in a taiga drama.

In the old days when TV dramas were made, the loud voices, the top dogs, so to speak, always prevailed. However, it’s important to make everyone’s voice heard; to create an atmosphere where you also listen to the opinions of the quieter people. I believe that our approach has given all the people involved a sense of security.

Were there any problems or did you get any negative feedback about portraying Yoshiwara and prostitution?

Fujinami: Well, we received different comments at NHK. There were pros and cons. Some people sympathized with the idea that it was important to depict not only the glamorous parts but also the sex industry. Other people wondered if it was okay to choose a story set in Yoshiwara for a taiga drama aired on Sunday at 8 p.m. There are some things I regret about the way the story was presented, and I wonder if I could have done it better, but when I made Tsutaju the main character, I knew that I had to depict his milieu properly because Yoshiwara is the environment where he grew up and the origin of his identity. If you don’t show the structure of exploitation, including the prostitutes and the poverty and inequality, then you can’t properly show where Tsutaju is coming from. After all, his driving force and the roots of his identity are in Yoshiwara.

Morishita: Setting a story in such a context is undoubtedly challenging and naturally invites mixed opinions. I accept the criticisms as they are. However, I feel discomfort when told that such historical aspects should not be addressed. As Fujinami-san pointed out, it is precisely because the protagonist was born into such circumstances that those books and paintings came into existence. To say that his environment and formative experiences are irrelevant and that his extraordinary talent alone was the reason for his success, was not a narrative I wanted to pursue.

Culture has the power to produce strong and influential lineages from deprived and unfulfilled environments around the world. I see this as a testament to human potential. That’s why I didn’t want to erase this aspect.

Also, despite the widespread condemnation of the sex trade as a source of many tragedies, the reality is that it has never been eradicated. Prostitution is the oldest and most enduring business in human history, intricately linked to human survival instincts. Eliminating it is likely as hard as eradicating war. Personally, I believe it may be impossible unless humanity itself ceases to exist.

Nevertheless, if we genuinely desire to bring about positive change in the present, we should understand and share the history, origins, and structure of such places. I cannot fully accept that they should not be addressed.

Talking about the late 18th century, a time when people like Tsutaju and Tanuma Okitsugu lived, you said that there were many parallels to the present day. What did you mean?

Morishita: As Fujinami-san mentioned earlier, society was in a state of stagnation, and though the overall situation was not bad, there were also many problems. One of those was inequality. While we cannot equate that era with the present, the gap between the haves and the have-nots had become bigger. That situation is the same as today; like back then, our world now is full of natural and man-made disasters. Moreover, rice farming has always been very important in Japan, but lately we are seeing rice shortages. The exact same thing happened in that era and everyone got angry, overthrowing all those who held power.

Now that I think about it, the French Revolution took place around the same time, in 1789. The rice riots in Japan happened in 1787. People rebelled around the same time on both sides of the globe. In Japan, the disappearance of rice triggered a shift in the balance of power. In France, wheat disappeared, eventually resulting in the overthrow of the government. I find that coincidence very interesting. The same thing occurs on both sides of the ocean, in places with very different languages, religions and ways of thinking. When people can’t eat, they get angry. Looking at it from another perspective, this is something all humans share, and I believe it is on this common ground that we can come together.

In ancient Rome, the emperors thought that to make people peaceful and quiet you only had to give them bread and games. This way of thinking seems to have been around for a long time.

Morishita: I can understand that. I’m also the type of person who can be satisfied if I’m given bread and entertainment (laughs).

Interview by Gianni Simone

To learn more about this topic check out our other articles :

N°150 [FOCUS] Debate : the crisis is not what we think

N°150 [FOCUS] The book empire is doing badly

Follow us !