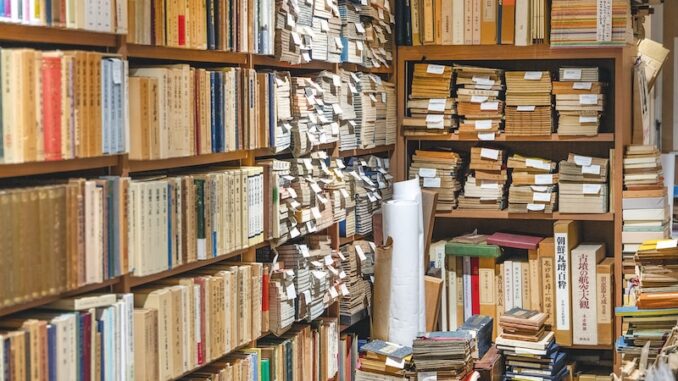

The number of bookstores continues to decline and authorities are slow to implement a policy to help them.

Japan faces a bookstore crisis as these vital cultural hubs rapidly disappear from towns nationwide. According to the Japan Book Distribution Association, the number of bookstores plummeted by about 50% over two decades, from 21,600 in 2000 to 11,024 in 2020. However, this figure includes offices and magazine stands without sales floors, meaning the actual number of bookstores offering a substantial selection is likely closer to 8,800.

By November 2024, a staggering 28.2% of municipalities were entirely devoid of bookstores, accounting for a quarter of the total, while 19.7% had only one bookstore. In part, this decline is closely linked to Japan’s steadily shrinking population, with small towns and rural areas disproportionately affected as aging residents and depopulation reshape communities.

This is a critical issue that threatens the decline of regional culture and risks widening the “knowledge gap” between rural areas and cities. At the same time, even urban bookstores are struggling to survive amidst soaring labor costs, utility expenses, and rents driven by rising land prices, leading to their steady disappearance. Addressing these challenges and implementing measures to revitalize and sustain bookstores is an urgent and pressing need.

The publishing market in Japan has been on a steady decline since its peak of 2.656 trillion yen in sales in 1997. By 2024, it had dropped to 1.571 trillion yen, even with the inclusion of electronic publishing. Focusing solely on paper books, the figure dwindles further to 1.056 trillion yen—less than 40% of the 1997 peak. Magazine sales have been hit especially hard, plunging from 1.563 trillion yen to just 411.9 billion yen in 2024, representing a mere quarter of their former glory.

The internet, social media, and video games are certainly to “blame” for the decline in book sales. A 2023 survey by the Agency for Cultural Affairs revealed a troubling trend: over 60% of respondents now read less than one book a month, a significant rise from 2018. Additionally, a record-high 70% admitted to reading less than before, citing increased internet usage as a major factor. Notably, 43.6% attributed their reduced reading to time consumed by devices like smartphones. With the growing adoption of generative AI, this decline in reading is poised to accelerate.

The dramatic decline of bookstores in Japan can be attributed not only to depopulation, ageing, and the internet but also to the unique structure of the country’s publishing industry. One of the most striking differences between Japan and Western countries is the role of magazines. In Japan, bookstores have historically sold large volumes of magazines, unlike their Western counterparts, where they are typically sold at newsstands or drugstores. The sight of freshly stocked magazines filling bookstore shelves daily is distinctly Japanese.

This reliance on magazine sales is also reflected in the revenue structure of Japanese bookstores. While Western bookstores primarily rely on profits from book sales, small and medium-sized Japanese bookstores have traditionally depended on magazine sales for their financial stability.

Given that approximately 70,000 new titles are released annually in Japan, magazines have long been a more efficient option for bookstores. They are easier to mass-produce, plan, and sell repeatedly, unlike books, which lack substitutability and are rarely purchased multiple times.

This internal subsidy structure, where magazine distribution supports book distribution, has sustained Japan’s unique system of delivering books to bookstores daily, even for single copies. Moreover, by minimizing distribution costs, Japan has managed to keep book prices remarkably low compared to other countries. For instance, in the United States and Germany, where the publishing systems rely solely on book sales, book prices are typically 1.5 to 2 times higher than in Japan.

Historically, magazine sales significantly outpaced book sales in Japan. At the peak of the publishing industry in 1997, book sales reached 1.093 trillion yen, while magazine sales soared to 1.563 trillion yen—1.5 times higher. During this era, the profitability driven by efficient magazine sales fueled a boom in bookstore openings across the country. However, by 2017, magazine sales had plummeted to 654.8 billion yen—approximately one-third of their peak—falling below book sales, which totaled 715.2 billion yen.

Again, the rise of the internet and social media has drastically reduced magazine sales, causing the collapse of this traditional business model. Consequently, small and medium-sized bookstores that heavily depended on them not only lost revenue but also the loyal customers who frequented their stores as part of their routine. Traditional bookstores, once a familiar sight near train stations and in shopping districts, were hit hardest, leading to their rapid disappearance from communities across Japan.

This new trend also disrupted the general distributors that managed expansive distribution networks built around magazines. With the exception of the top two general distributors, Nippon Shuppan Hanbai and Tohan, along with a few specialized distributors, other leading players – including Osakaya, Kurita Shuppan Hanbai, and Taiyosha, ranked third, fourth, and fifth respectively – succumbed to bankruptcy one after another.

Even Nippon Shuppan Hanbai and Tohan have both reported significant losses in their publishing and distribution operations in recent years. Remarkably, Hirabayashi Akira, president of Nippon Shuppan Hanbai, disclosed that the company’s book division has been operating in the red for more than 30 years since his tenure began.

The rise of online bookstores has made matters even worse. Amazon began selling books in Japan in 2000. In addition to a wide selection of publications published in Japan, it has introduced services such as free shipping to attract customers. According to the 2024 edition of the Actual Amount of Publication Sales report by Nippon Shuppan Hanbai, in 2023, approximately 58% of total publication sales were attributed to physical bookstores, while around 21% came from online outlets. The latter has been steadily encroaching on the former’s market share.

Kodansha and Yomiuri Shinbun, one of Japan’s leading publishers and newspaper companies respectively, have recently published a joint statement in which they point out that in some countries, books are regarded as “essential items of life” and “cultural properties,” with bookstores and related businesses receiving substantial support to preserve cultural heritage. Globally, initiatives to promote print culture and support bookstores are gaining momentum. France and Germany, for instance, have introduced the Culture Pass system to encourage cultural engagement among young people. In France, this program allocates 20 to 300 euros per individual aged 15 to 18, which can be spent on books, manga, concerts, or museum tickets. This initiative has not only boosted book sales but also contributed to the popularity of Japanese manga. Additionally, both countries offer subsidies and loans to assist in the establishment or renovation of bookstores, reinforcing their commitment to sustaining the print ecosystem.

In stark contrast, public support for bookstores in Japan remains inadequate at both national and local levels, and their decline appears relentless. Although programs such as the Small Business Sustainability Subsidy, IT Introduction Subsidy, and Business Restructuring Subsidy exist, they are general schemes not specifically tailored to bookstores. These initiatives have failed to effectively reach bookstore managers, hindered by cumbersome application processes and strict screening criteria, resulting in low utilization rates. While many bookstores grapple with the challenge of finding successors, aspiring bookstore owners attend opening courses with great enthusiasm, yet their passion remains largely untapped.

Kodansha and Yomiuri’s appeal continues by urging the national and local governments, alongside all businesses connected to the book industry, to unite to implement comprehensive measures aimed at revitalizing bookstores as vital cultural hubs. Equally crucial is fostering a love of reading among future generations. “By creating more opportunities for children to engage with books from an early age,” their statement reads, “we can help them discover the joy and lasting benefits of reading, ensuring a brighter future for both readers and bookstores alike.”

In late February, during the House of Representatives Budget Committee, Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry Muto expressed the government’s commitment to tackling the decline of local bookstores by providing management support, including advancing digitalization in their operations. To this end, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry established a Bookstore Development Project Team under the Minister on March 5th, marking the first full-scale effort to address this nationwide issue. Bookstores will be recognized as essential cultural hubs that promote local culture through books and magazines. The team will also explore support measures for unique initiatives, such as hosting reading events and integrating café galleries, to revitalize these vital community spaces.

Gianni Simone

To learn more about this topic check out our other articles :

N°150 [FOCUS] Debate : the crisis is not what we think

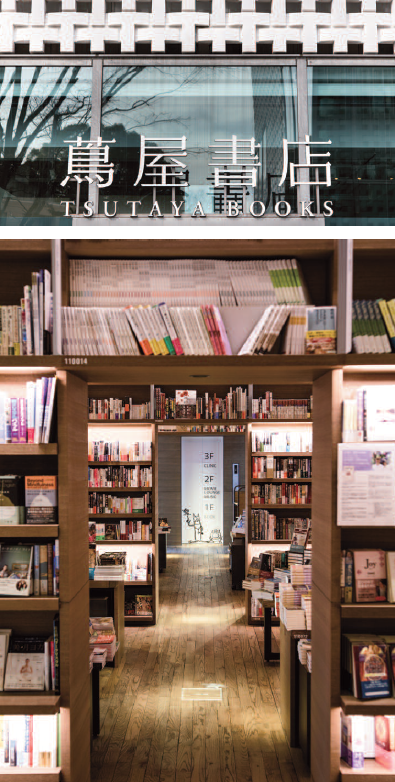

N°150 [FOCUS] Drama : Tsutaya, king of publishing of Edo

Follow us !