For Kakio Inja, the world’s difficult situation for bookstores can be explained by past bad decisions before anything else.

Most people lament the disappearance of bookstores in Japan and the general decline of the publishing industry is a shame. However, occasionally, one hears slightly discordant opinions from insiders who like to point out some of the discrepancies in the debate.

One such individual is Kakio Inja, the pen name of a retired reporter and editor with a background in newspapers and publishing. ‘Inja,’ meaning hermit, reflects his current lifestyle. Now residing in Kakio, a district in Kawasaki, he is primarily active on the platform Note, where he shares insights on culture, society, and politics, enjoying a thoughtful retirement.

Inja highlights an intriguing recent trend: “While the number of bookstores is declining, the average sales floor space per store is expanding,” he says. “In other words, the crisis is mainly hurting small and medium-sized shops, whereas larger bookstores and chains are thriving. Last year, for example, Kinokuniya saw a decrease in revenue, but it achieved its sixth consecutive year of increased profits. I believe the reasons behind this are brand power and these big stores’ capacity to offer an extensive selection of books.”

“When I previously interviewed Kinokuniya Chairman and President Takai Masashi, he said that the Shinjuku main store houses an impressive 1.2 million books. Many of these titles, however, don’t sell even a single copy annually. Takai emphasized that bookstores should stock more than just popular books, asserting that one of their essential roles is to safeguard knowledge.

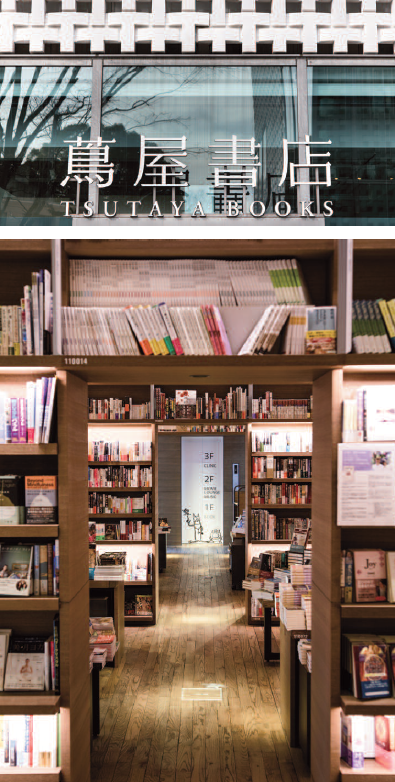

“Another type of bookstore that will survive is Tsutaya. These stores incorporate cafés and feature expertly curated book displays, appealing to customers with their style and ambiance. The Daikanyama T-Site in central Tokyo and Tsutaya Electrics in the suburbs exemplify this model, which has now spread nationwide, attracting visitors who value the unique atmosphere these spaces offer.”

Inja does not pull punches when commenting on the book trade, asserting that the shops should share at least part of the blame for their current misfortunes. “Stories like ‘Let’s protect the local bookstore’ or ‘Someone quit their job to start a bookstore’ are celebrated as heroic narratives,’ he remarks. “The media love these tales. But don’t be misled by the bookstores’ positive image. Let’s not forget that those shops have managed to thrive for years by exploiting part-time employees. I once heard this from a bookstore owner: ‘Because bookstores have a positive image, serious and talented people are willing to work for low hourly wages. It’s a big help!’ In other words, the owners take advantage of their employees’ motivation and goodwill.

“Having worked in a bookstore, I can attest that it’s physically demanding labor. You must carry heavy stacks of magazines, pack large quantities of returned books into boxes, and perform tasks that strain your back. Many college-educated women endure such hard work for low hourly wages, motivated by the belief that they are serving as cultural bearers.

“Bookstores, traditionally, have operated as an ‘easy’ business model largely due to their reliance on inexpensive part-time workers. Since publishers handle advertising for their products, bookstores simply display the promotional materials sent to them, covering their walls with posters. Moreover, the resale price maintenance system and the ability to return unsold books without cost have allowed bookstores to sell at fixed prices without worrying too much about sales strategies.

“As a child, I perceived bookstore owners as cunning characters who dusted books ostentatiously in front of customers, disrupting their browsing. Such portrayals were common in manga and anime. In reality, many owners and managers spent their time sipping tea in the backroom, occasionally surfacing to monitor browsing customers or catch shoplifters.”

Inja challenges the widely accepted notion that publishing is in a recession and books are no longer selling. “If bookstores are declining,” he argues, “publishers should be struggling as well. While many publishers are indeed small or medium-sized enterprises facing difficulties similar to those experienced worldwide, the top publishers are thriving. I worked at such a company myself, so I know the situation very well. However, the top publishers are reporting unprecedented profits. Shueisha and Shogakukan, for example, are so highly regarded that they rank among the most coveted employers for university graduates. A friend of mine joined one of these top publishers, and he said that not only was he highly paid, but he would also receive a good company pension.”

Why are publishers thriving while local bookstores are going bust? Are books selling or not? According to Inja, it all comes down to how one defines a book. “The short answer is that the number of printed books is decreasing, but the manga market is growing rapidly.” Indeed, data from 2023, released by the Publishing Science Institute, shows that the comics market now accounts for nearly half of the total publishing industry. Manga sales, including both print and digital formats, rose 2.5% from the previous year to 693.7 billion yen. While combined sales of paper comic books and magazines dropped 8.0% year-on-year to 210.7 billion yen, digital comics grew 7.8%, reaching 483 billion yen.

This marks the sixth consecutive year of expansion for the manga market, driven primarily by digital sales. By the numbers, paper comics constituted 30.4% of the market, while digital comics accounted for 69.6%, with digital sales comprising approximately 70% of overall revenue. According to the 2024 Publishing Index, the share of comics (paper and digital combined) in the publishing market increased by 2.0 percentage points year-on-year to reach 43.5%. “If that’s the case,” Inja suggests, “bookstores should cut their inventory of traditional books by more than half and focus on selling comics, which are a growing product. If a store goes out of business because it doesn’t stock popular titles and only carries unsellable items, it’s the store’s own fault.”

Inja acknowledges that merely adjusting the ratio of books to comics on display won’t resolve the issue, as sales are likely to continue declining. “The truth is,” he explains, “only digital comics are experiencing growth. E-comics have surged by an impressive 7.8% compared to the previous year. To summarize, the comic market is poised to overtake the print market in the near future; within the comic market, only e-comics will continue to grow; and ultimately, e-comics alone will comprise more than half of all publishing. Which, in a way, paints a bright future, doesn’t it?”

The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry has expressed its intention to support the content industry, encompassing publishing, movies, and music. 2As the economy matures,” the official statement reads, “in order for our country’s services and products to be competitive abroad, we need to add new value through culture.”

In response, Inja remarks, “If that’s the case, shouldn’t we consider further expanding the comics market, which has already demonstrated its international appeal and competitiveness? Let’s celebrate manga as a cultural asset.”

Reactions on social media to the Ministry’s declaration included calls from bookstore owners for the government to require libraries to purchase books from local stores.

Known for his provocative remarks, Inja offers his perspective on the matter: “Why did I stop buying books? Because I can borrow them from my local library. Why don’t I read manga? Because they don’t have them in my local library. I want to read manga and keep up with what young people are talking about, but poor old people like me can’t spend money on comics.

“The reason manga publishers are making so much money is that they’ve built a system where you can’t enjoy manga and anime unless you pay. To protect this system, copyright-infringing websites are heavily cracked down on. On the other hand, libraries are stocked with books, including popular works, which can be read for free – though there is often a wait.

“Now, my question is, why are libraries filled with books but devoid of manga? It’s due to the mistaken belief that books represent culture. This value system elevates novels and non-fiction as superior forms of media. Consequently, national and local governments funnel tax money into libraries to lend books, which reduces book sales and ultimately harms bookstores.

“There is a widely accepted international understanding that manga and anime are commercial products, with their rights recognized as private property, be it Disney’s intellectual property or works by Fujiko Fujio. Conversely, there is an ingrained belief that other forms of printed information represent the common heritage of humanity. This belief underpins the concept of libraries, which exist to provide such information for free.

“Publishing is often considered more significant than monetary gain, and book publishers, unlike other lowlifes, are perceived as engaging in essential cultural work, even when their methods are inefficient or their operations unproductive. However, government intervention, driven by the belief in the importance of print culture, ends up overprotecting the industry, inadvertently contributing to its decline. One could argue that print culture is effectively strangling itself.

“The only way to save local bookstores, I believe, is to challenge the misguided notion that books are inherently superior to comics. From now on, libraries should focus exclusively on manga, directing their entire budgets toward acquiring comics. As a result, manga would be freely accessible in libraries for all, while books would only be available for purchase at bookstores.”

To challenge the bookstores’ lofty image, Inja draws an unexpected comparison to pachinko parlors, those once-ubiquitous gaming venues where people gamble by playing pachinko, a mix between pinball and slot machines.

“As I said, bookstore-related news often turns into heartwarming stories,” he argues. “I think it’s unfair. The number of pachinko parlors is declining just as much, but you don’t see newspaper reporters lamenting that. It’s a matter of discrimination: bookstores are seen as cultural institutions, while pachinko is dismissed as mere gambling.

“But games are culture, too. And perhaps even more importantly, do you know the difference in market size between the publishing and pachinko industries? The publishing industry generates around 1.5 trillion yen in sales, while the pachinko industry brings in 15 trillion yen – ten times as much. Just visit a pachinko parlor and you’ll see customers feeding 10,000 yen bills one after another into ball-refilling machines. So, the disappearance of one pachinko parlor in front of a station has the same economic impact as the closure of ten bookstores.”

Of course, brick-and-mortar bookstores are only a segment of the publishing industry, serving as physical outlets for paper books. A significant factor contributing to their decline is the rise of online bookstores. While Amazon does not disclose its sales figures, it likely surpasses the largest bookstore chains. The reality is that sales of paper books have been steadily declining since the late 1990s, whereas digital publication sales have been soaring in recent years.

“The decline in print and the shift to electronic books are not the only reasons why bookstores are going under,” Inja points out. “Yes, okay, one issue is the low-profit margins of bookstores. But that’s not the point. The real problem lies with the resale system which mandates that retailers sell products at the listed price set by the publisher. This practice violates the Antimonopoly Act because manufacturers restricting retailers’ pricing undermines fair competition.

“When a retailer buys a product, ownership transfers from the manufacturer to the retailer. Retailers should be free to sell items at any price they choose. That’s why standard products don’t have a listed price – they only display a ‘manufacturer’s suggested retail price’. The resale system, however, is an exception to the Antimonopoly Act. Even more troubling, while it technically violates the Antimonopoly Act, it is not recognized as such.”

“In Japan, this system applies to copyrighted works such as books, magazines, newspapers, and CDs. Essentially, the books displayed in bookstores do not technically belong to the stores; they remain the property of the publishers. Unsold items are simply returned to the publishers. Bookstores act as mere showcases for these products. When books were selling well, this model functioned effortlessly, but now that sales have plummeted, bookstores find themselves powerless to adapt.

“I’ll give you an example of why listed prices don’t work. Now there are many books about the Ukrainian War, right? But the situation in Ukraine is constantly changing. I don’t think those books will sell in a year’s time. Just as newspapers from a year ago have little value today, books on rapidly changing topics struggle to maintain relevance over time.

“However, bookstores have no choice but to keep selling those books at the same listed price they had when new. I say, sell them at full price when they are valuable, and reduce the price as their relevance declines. That’s standard business practice, but bookstores can’t do that.

“In contrast to Japan, the number of bookstores in America is rising. While major bookstores once faced significant challenges from Amazon, independent bookstores have recently experienced a resurgence. This is partly due to the fundamentally different approach to retailing in the United States. Once a book becomes a bestseller, it is often sold at substantial discounts – sometimes even at half price – by mass retailers like Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Walmart, and Costco. Under these circumstances, independent bookstores avoid carrying bestsellers, as they are less profitable. Instead, they focus on books that can be sold close to the listed price without discounts, ensuring higher profit margins.

“This is why independent bookstores in America don’t stock trending bestsellers but instead choose books they believe will sell in the future. Whether they sell or not ultimately depends on the customer. Unlike Japan, where distributors pre-select and send books to stores, American publishers’ sales representatives visit bookstores to secure preorders for first editions. Discerning bookstore owners carefully review publishers’ catalogs – usually released at least six months before publication – and decide what to stock and in what quantities. They carefully select what is likely to sell and aim to maximize profits by selling at the highest price possible. In Japan, by contrast, bookstores automatically receive a steady stream of books they didn’t request and end up returning many unsold copies.

“During Japan’s deregulation and administrative reform movement in the 1990s, the government considered abolishing the resale system for copyrighted works. However, the newspaper, magazine, and book industry associations vehemently opposed this idea. Instead of highlighting the potential benefits of eliminating the resale system, they mounted a strong campaign against deregulation, claiming it would ‘destroy print culture.’ They enlisted prominent cultural figures and dedicated entire pages to equate deregulation with an ‘oppression of free speech.’ Now, they are facing the consequences of those decisions.”

Jean Derome

To learn more about this topic check out our other articles :

N°150 [FOCUS] Drama : Tsutaya, king of publishing of Edo

N°150 [FOCUS] The book empire is doing badly

Follow us !