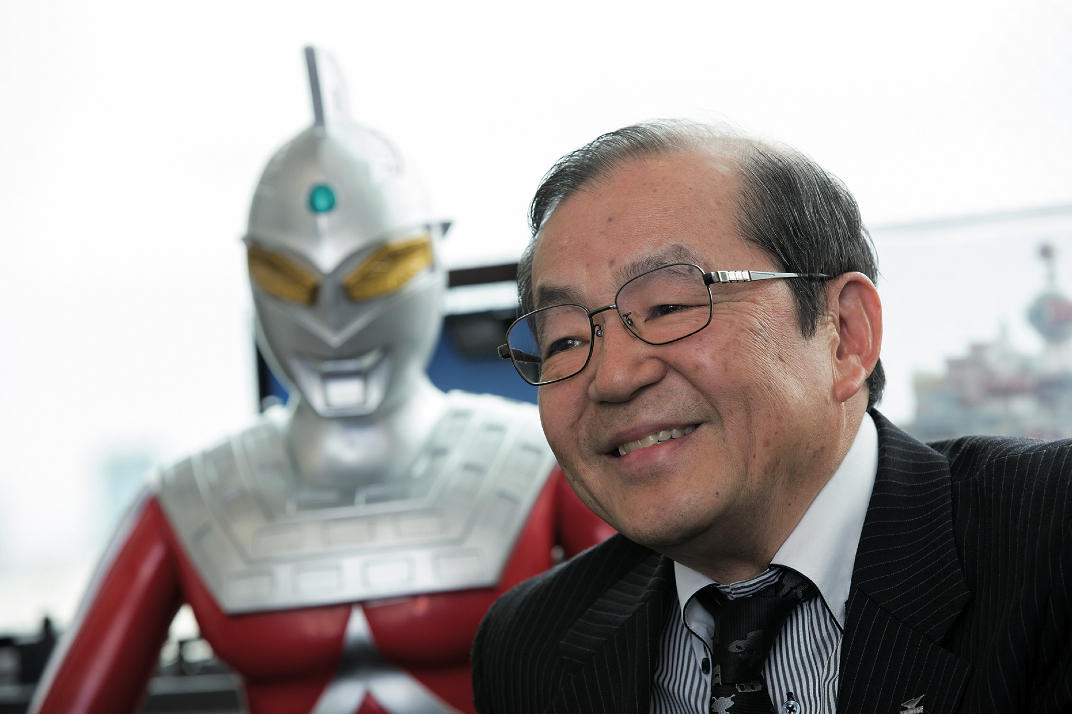

Farmers have long been supported by a system that allowed them to to influence politics, but not anymore. There is growing concern among people in Japan about the future of local agriculture, due both to American trade pressure and the Abe Shinzo administration’s apparent lack of interest in the matter. Zoom Japan has discussed these issues with Yasuda Setsuko, the head of both the Japan Organic Agriculture Research Centre and the Vision 21 Information Centre.

When did you first get interested in food and nutrition issues?

Setsuko Yasuda: When my children started elementary school. I attended a seminar on the subject and I was struck by the statement that the way children eat can change their life. That’s when I decided to delve deeper into these matters. Later on, I had a chance to work for a consumer association. At first I was active in the anti-nuclear movement, and it was while researching the problem that I realized how poor rural communities around Japan had been persuaded by the government into accepting nuclear plants with the promise of tax breaks and other economic benefits. So I asked to be put in charge of food safety and agriculture.

What do you think about the future of Japanese agriculture?

S. Y.: All recent trends point to the fact that the government is not doing enough to protect national rice production. This is very troubling because for a very long time rice has not only been our staple diet, it’s been at the heart of Japanese life and culture. Collaboration and sharing, for example, is very important in Japanese society, and the origin of this can be found in the way rice is produced on a communal level. This approach is also stressed during the local festivals that are held first in summer, when we pray for a plentiful harvest, and then in autumn, this time to thank the gods for receiving it. Also, up to the second half of the 19th century, economic wealth and one’s station in life were calculated in rice. In other words Japanese society, culture and economy have all been built around rice culture. If we throw away all the hard work our forefathers have done we are going to destroy both the environment and our food culture. That’s why I think the government’s current agricultural policy is a recipe for disaster.

This recent trend is quite opposite to the government’s traditional attitude towards farmers, isn’t it?

S. Y.: Yes, indeed. According to the Staple Food Control Act of 1942, the government is formally in charge of all rice production, distribution, and sales. Until 1995, the government used to buy all the rice produced in Japan before selling it at a relatively high price (agreed on with the agricultural cooperatives) in order to support the farmers. At the same time rice imports were banned. However, since the end of the 1980s, the United States have applied pressure to get the government to lift the ban on foreign rice. In the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement of Tariffs and Trade (GATT) negotiations in 1990, Japan refused to agree to concessions, but now the same thing is being debated in connection with the Trans- Pacific Partnership (TPP).

What do you find the most troubling thing about the recent trade developments?

S. Y.: It’s what they call “minimum access”, i.e. the way the US is trying to force Japan to accept rice imports just because they have a surplus production of rice. It has nothing to do with our food needs. It’s just that they are looking for new markets to off-load their excess production, while using food as a weapon to impose supremacy on the region.

Actually the Japanese are consuming less rice than ever, aren’t they?

S. Y.: You’re right. In 1960, for example, the average annual consumption was 118kg per person. Now, on the other hand, it’s only 61kg, i.e. about half the rice we used to eat 50 years ago. That puts our current rice needs at about 8 million tonnes per year, yet we are asked to import 10% of that rice (770,000 tonnes) from the US.

Why isn’t rice as popular in Japan today as in the past?

S. Y.: After the war Japan imported many new ideas from America. One of them was that a bread-based diet was better for our health. At the time it was widely advertised that eating rice made you stupid (laughs). At the movies we would see all those big healthy-looking actors, and of course they all ate bread and meat and drank milk. So following an American request, for many years the Japanese Government provided only bread for school lunches. Oddly enough, it is only recently that rice has been reintroduced for school lunches. But in Japanese homes most people now eat bread or pasta at least once a day, and of course we eat a lot of meat (annual individual consumption has shot up from 30kg to 137kg in 50 years). And most meat and wheat, together with other products like soya beans and corn, are imported mainly from the US. As a consequence, Japan’s food self-sufficiency has gone down from 80% in 1960 to only 39% in 2006.

You have mentioned the TPP. Why do you think this agreement poses a threat to Japanese agriculture and rice production in particular?

S. Y.: Because the US want Japan to get rid of any import tax on foreign rice (i.e. American rice). That would have a disastrous effect, as 90% of national production would be wiped away by a total liberalization of rice trade. Only the strongest, most popular varieties like Niigata Prefecture’s Koshihikari would keep selling well. These are comparatively expensive, but are very popular with people who can afford to buy them. Another thing that worries me are the big American biotechnology companies like Monsanto. After the war, the occupation government decided to prevent the reconsolidation of farmland by making it so that only the people who did the actual farming (i.e. the small farmers) could own large areas. It prevented joint-stock companies from gaining control of the land. It was a good thing because big companies only think about the bottom line; when times are bad they can easily switch to more lucrative crops. However, the Abe administration is now talking about renting land to these companies, including foreign corporations. Monsanto, for example, is already growing rice in Tochigi Prefecture. My worry is that in the not so distant future big business will gradually take control of Japanese agriculture, only pursuing its own interests at the expense of local people.

Some experts contend that considering the current situation (depopulation of rural areas, remaining farmers getting old, increasing production costs, etc.) it would be probably better to buy cheaper rice from other countries.

S. Y.: It’s true this opinion seems to be quite popular in certain political and economic circles. But are we sure this is not a potentially dangerous decision? Maybe for a tiny country like Singapore it makes sense, but Japan still has more than 100 million people. Is it really safe to trust international free trade when our food self-sufficiency is at risk?

Can you tell me about the relationship between agrochemicals and the destruction of nature?

S. Y.: This is a sore point because Japan is the world’s number one country in terms of chemicals used in agriculture. According to a 2004 OECD survey, Japanese farmers use almost 16kg of chemicals per hectare. In comparison, American farmers only use 2kg/ha. Some time ago a US trader pointed out this fact to prove that American rice was not only cheaper but even safer than Japanese rice. However, there’s an important thing we must consider. If we analyse the final product, that is the rice itself, we find more traces of chemicals in American rice than in Japanese rice. The reason is that American farmers use a lot more pesticides and insecticides after harvesting the rice. These chemicals stick to the grains and don’t go away. By contrast, in Japan we mostly use herbicides that are spread at the beginning of the growing cycle. They gradually disappear during the growing process and only a minimal amount remains at the time of harvesting.

Does that mean we shouldn’t worry too much?

S. Y.: Well, actually there’s a big problem right now with neonicotinoids, a class of neuro-active insecticides whose use has been linked to the widespread

disappearance of bees, which in turn has negatively affected agriculture as many crops are pollinated by bees. Neonicotinoids have become very popular because compared to other insecticides they cause less toxicity in birds and mammals. However, high levels of neonicotinoids in insects cause paralysis and death. Not only that, according to recent tests it appears that even small children can be negatively affected by them. In 2013, the European Union and a few non EU countries restricted the use of certain neonicotinoids. However, in Japan, where these insecticides are widely used against shield bugs, the government is doing nothing. Unfortunately, the agrochemical lobby is very influential and has strong connections with politicians. Giant chemical companies like Sumitomo Kagaku or Japan Agricultural Cooperatives (JA) that sell the chemicals to the farmers and the helicopter companies that spread them on the rice fields – they all have a strong economic interest in keeping things as they are.

The number of Japanese farming households has declined in recent decades. Currently most farmers are over 65 years old, while more and more people in their 20s choose to live in the cities. In your opinion, what should the government do in order to create a new interest in agriculture among young people?

S. Y.: The main problem is all those complicated laws and regulations that often discourage people from even trying this kind of business. Recently, for example, there’s been a growing demand for organic farming, but just reconverting the land to the organic method takes about three years. Under these circumstances, the government should support young enterprising farmers through long-term rental contracts and some sort of financial aid. These people need to know that they are not being left alone in their battle to preserve our agricultural heritage.

Interview by Jean Derome

Photo: Jean Derome