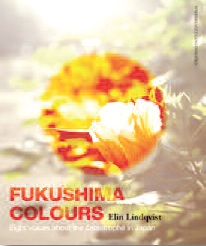

Journalist Elin Lindqvist publishes a wonderful book in which she puts the tragic events of 11th May 2011 into perspective.

Journalist Elin Lindqvist publishes a wonderful book in which she puts the tragic events of 11th May 2011 into perspective.

Born in Japan in 1982, Elin Lindqvist evidently remains very connected to the country although she now lives in England. After the earthquake and the tsunami, that were not only disastrous for the north east of Japan, but also led the country into its most serious nuclear crisis ever, the journalist traveled to the area in order to cover the events for Swedish newspapers. This new experience resulted of in a wonderful book called Fukushima Colours. In it she raises the principal questions that concern the Japanese today with sensibility but without ever resorting to caricature. By giving a voice to those who experienced the disaster, she rightly reminds us that these events should not be forgotten. Elin Lindqvist answered our questions about her book.

Can you explain your relationship with Japan?

Elin Lindqvist : I was born in Japan and, although I only lived there for two years as a child, I have maintained a very strong relationship with the country. I moved there on my own as a seventeen year old to study for a year and then again in my twenties for another year of studies while also working as an English teacher. Later on, I traveled back and forth, on both long and short journeys, and all the while I maintained strong ties with friends and Japanese people I consider to be family. That is why, when the earthquake occurred last year, and I saw the terrifying images unfolding on my TV screen in England, I knew that I had to go there.

What was your main motivation in writing this book?

E. L. : I felt that the way Western media reported the nuclear crisis and the direct aftermath of the tsunami was shallow, dramatic and sensationalist. So I called up Sweden’s largest newspaper, the Aftonbladet, on which I had worked previously, and asked them if they needed a reporter. This was just a few days after the tsunami had occurred and it was at the height of the nuclear catastrophe. The Aftonbladet and a lot of other Western media channels were calling back their reporters because of the potential danger. We agreed that I should go. I wanted to report about on the crisis in another kind of way. I wanted to talk to people and really try to understand how people in Japan perceived the situation. Once I had traveled to the devastated areas, I understood and felt very strongly that I could not leave it at that. I could not just go home and move on while people in Japan were going to have to deal with the consequences of this triple catastrophe for years to come. In May 2011, I was able to return and write again for Swedish newspapers, taking the ‘hundred days after the catastrophe’ as my theme. That was when I decided that this had to become a book.

How did you pick the people for the book? And in your opinion, which story is the most powerful?

E. L. : Some of the people that I interviewed for the book are people I have known for many years. Others I met in the middle of the crisis for the first time and bonded with them. All have become important to me. But if I had to choose just one person’s destiny or testimonial, I think it would have to be Endo Minoru from Tomioka, one of the towns within the 20 km safety zone around Fukushima Daiichi. I admire his strength and his determination not to give up.

How do you see the future of Tohoku area and Japan?

E. L. : I think that the rest of the world will learn from what happened in Tohoku in general and in Fukushima in particular. The truth is that nobody really knows for sure what effects the radioactive spills will have on Fukushima prefecture, its inhabitants and the Sea of Japan. What Japan decides to do relating to its energy policies and nuclear energy is going to be very interesting and potentially groundbreaking for the whole world’s energy industries. Similarly, the coastal communities of northeastern Japan have yet to decide how to rebuild and how to protect people, in the future, from potentially even higher tsunamis, and I think that is a key development as well. At the moment, 344,000 people live in temporary housing all along Tohoku’s coast. 80,000 people have been evacuated from the safety zone around Fukushima Daiichi. It will take a long time before it becomes clear what lies in store for them. For the rest of the world and even for most people in Japan, life goes on. But not for these people. It is important to remember and to listen to them.

Interview by Odaira Namihei

REFERENCE

FUKUSHIMA COLOURS, by Elin Lindqvist, Bokförlaget

Langenskiöld editions, £18