Since 2006, the Chukiren Peace Memorial Hall has been fighting to present the truth about the war.

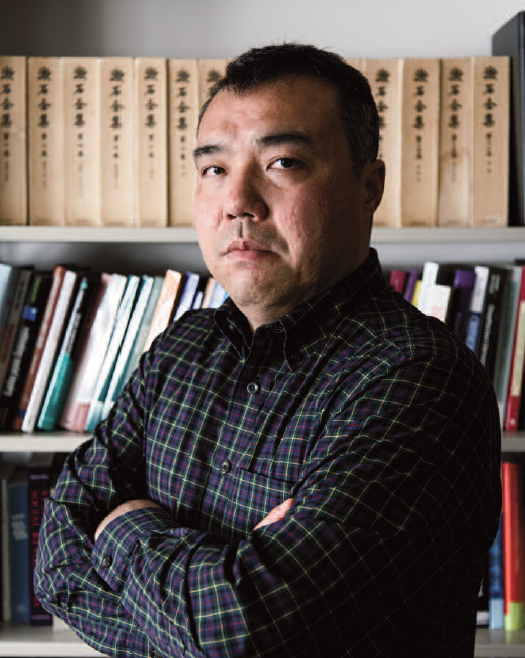

If the Yushukan Museum represents the attractive, glossy, rose-tinted version of Japanese history, its direct opposite can be found about 30 kilometres north of Tokyo, in Saitama Prefecture. After getting off at the tiny Tsurugashima Station, we hail a taxi and direct the clueless driver to a one-storey building lost among an endless sea of fields. Inside we find books everywhere – some of them neatly arranged on shelves, many more inside the many cardboard boxes piled up in each room and even the corridor – and the three people who guard these precious documents for which the place is known. Welcome to the Chukiren Peace Memorial Hall, a resource centre devoted to teaching the truth about Japan’s war-time atrocities. Founded in 2006 by the Association of Returnees from China, it houses many important documents including almost 200 memoranda in which war veterans tell of all the grisly things they have done and seen while posted in China. Today Serisawa Nobuo and Miyamoto Naoko – the only two regular members of staff – welcome us, together with Keio University’s Emeritus Professor and Chukiren Chief Director, Matsumura Takao.

You have to admit this place is rather off the beaten track.

Serisawa Nobuo: When it started, former chairman Niki Fumiko used to live next door, so she chose the place partly out of personal convenience. Also, we can’t afford Tokyo’s high prices. Even after becoming an NPO, we haven’t accepted the government’s admittedly paltry financial aid. We want to preserve our independence, so we only manage to exist through membership fees, our fund-raising campaigns, and the help of about 20 volunteers. Of course, for many people trekking all the way to this place is rather inconvenient, but we are not a common public library. Most of our visitors are scholars and journalists who need to consult our documents and books for their research. That said, everybody is welcome here.

The other day when I mailed you to arrange the interview, you seemed to be worried we might be right-wingers…

Serisawa Nobuo: Yes, that’s true. The Association and this place have attracted many attacks from ultra-conservative groups. I remember when [notoriously nationalist] Sapio magazine once wrote a four-page article portraying us as a bastion of anti-Japanese sentiment. If right-wingers catch even a small factual mistake on our part they blow it out of all proportion, so we must be very careful.

While Chukiren’s mission is to present the truth about WWII, many conservatives – led by the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) – persist in denying the facts despite all the proof and testimonies now available. What do you think of the ongoing textbook controversy?

Matsumura Takao: The origins of this problem date back to the mid ‘50s when the Ministry of Education rejected several social studies textbook manuscripts. Arguably, the most famous victim of such a policy was respected historian Ienaga Saburo, who fought a long battle with the Ministry and even sued it in 1965 in what is considered, to this day, the most famous challenge to textbook censorship. Then in 1996, a group of nationalists founded the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform with the aim of fighting what they considered a “masochistic view of history”, and injecting a sense of pride in Japan’s past. In order to achieve their goal they have published their own textbooks that, of course, present a biased, one-sided view of many past events. The problem with textbook selection is that Japan is the only “democratic” country where the Ministry of Education has the right to impose its textbook choices on schools nationwide. Three years ago, for example, a few towns in Okinawa rejected this prejudiced way of presenting history, and independently adopted a different textbook, only for the Ministry to demand “corrective action” against their act of rebellion.

Are you worried by how things have evolved in the last few years?

Matsumura Takao: Of course I am. This is a clear attempt on the part of the LDP-led government to hide what really happened between Japan and its Asian neighbours before and during the war. On top of that, the government’s attack on civil liberties has lately increased in pace, most notably with the recent enacting of the State Secrets Law and the attempt to reinterpret the Constitution in a nationalistic, militaristic way.

Why is this law so dangerous?

Matsumura Takao: In 1923, two years after the Great Kanto Earthquake destroyed Tokyo, the government promulgated the Peace Preservation Act. Now, three years after the 11th of March disasters, the government has come up with this law. It seems that after a big calamity and the ensuing crisis, confusion and social turmoil, the authorities feel the need to take control of the situation in order to stifle any criticism of the political elite. This time, of course, the nuclear plants are the biggest problem, and Mr Abe doesn’t like the growing popular rejection of nuclear energy. So the LDP’s goal is to crush the opposition. It’s true that many other countries have similar laws to protect national security and classified information, but these papers are routinely withheld for 30 years, whereas in Japan they can be withheld for up to 60 years, sometimes even longer. That’s just incredible! Even the United States has expressed concern, and that’s really saying something! Only in Japan can you find such an unfair law. Unfortunately, this is nothing new. Indeed, this is a country where embarrassing documents magically disappear. For the last four years, for instance, I’ve tried to obtain some documents related to the infamous Unit 731. All along, the Ministry of Defence has said it can’t find them. This is despite that fact that in 1986

the American authorities stated in a public hearing that they had returned them to the Japanese government at the end of the ‘50s. Therefore, last November, I was forced to sue the state. Now, under the present law, even requesting a certain document can be punished with a 10-year jail sentence. In such conditions everybody – journalists, scholars, etc. end up censoring their own work out of fear. Freedom of speech is in danger. That’s why many municipalities are opposing the law and people around the country are organizing public assemblies to discuss the matter.

Mr Abe’s foreign policy has been criticized by several countries. It doesn’t bode well for Japan’s international standing.

Matsumura Takao: It’s very serious because Japan is losing the trust of an increasing number of countries. Japanese politicians are against issuing apologies, with the courts throwing out each and every case; in other words it’s a general state of denial. This lack of trust though, does not extend to the people. I can testify that Japanese and Chinese people enjoy a friendly relationship. We at Chukiren in particular, have always had many exchanges and even last July a Chinese delegation visited us. This is very important because in such conditions the authorities can’t persuade the population to go to war. It’s only the government that keeps antagonizing our neighbours and the media are doing nothing to stop it.

Speaking of the media, recently NHK’s Chairman Momii Katsuto and board member Hyakuta Naoki have publicly stated that wartime sex slaves didn’t exist and that the Nanking Massacre had been exaggerated.

Serisawa Nobuo: It’s a real shame. Journalists are supposed to be the government’s watchdog, so why aren’t they doing their job?

Matsumura Takao: The sad reality is that journalism in Japan is hopeless. There are, of course, people inside of NHK who oppose Momii’s opinions but there’s nothing they can do. Whenever a journalist tries to do his job he is transferred to a faraway place where he can do no harm. It’s really a deplorable situation. Particularly in the aftermath of The 2011 disasters, NHK’s approach to news broadcasting has changed. For example, when the 8% consumer tax came into effect, the anchor-man urged everybody to accept the tax hike because, “this money is going to be used for social security”. Not only is this a lie, but this patronizing style does not belong on NHK. Unfortunately, it’s not only NHK. All major papers – the Yomiuri, the Mainichi, now even the Asahi – have changed for the worse; only the Tokyo Shimbun is doing its job properly.

What are your thoughts on the current state of politics in Japan?

Serisawa Nobuo: It’s a very serious situation. About a year and a half ago, I toured several European cities where I spoke about The political, economic and social consequences of the 2011 disasters. I had the chance to meet many people, and nobody understood why the government was trying to revive the nuclear programme, even though 70-80% of the Japanese people opposed nuclear energy. That’s when I realized that Japan’s constitution and the separation of powers notwithstanding, this is not a democratic country. Or to put it differently, things haven’t really changed since the pre-war period. That’s why it is important to continue protesting and to oppose this increasingly authoritarian government.

Itnerview by J. D.

Photo: Jérémie Souteyrat