Are animation films an example of a kind of Japonisme, which continues to reinvent itself?

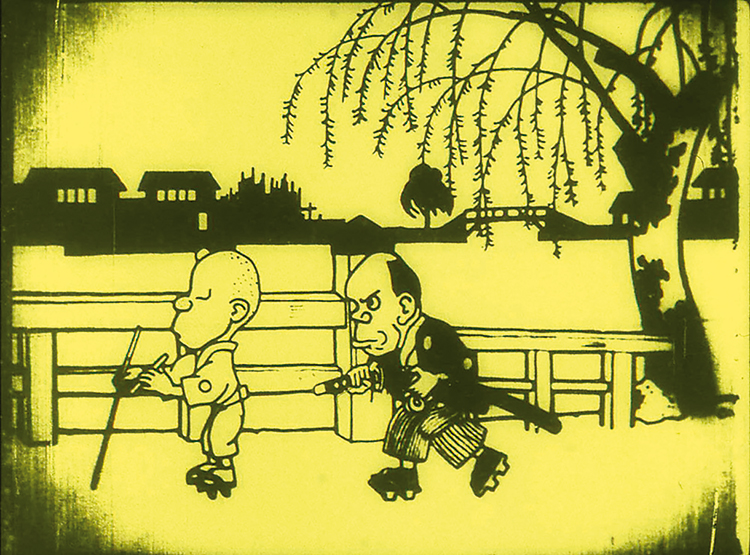

The Blunt Sword (Namakura katana) by Kouchi Jun’ichi (1917).

T he Japanese film animation industry is a real labyrinth. It’s an extraordinary maze of ideas, whose influence on the international scene, where it first made inroads twenty years ago, is still on the increase. Its recognition abroad, thanks to the work of some amazing film makers, dates back to around the start of the 21st century, and marked a turning point in the public’s perception of “Japanese cartoons”, and led to a timely change in the opinions of the leading critics of the time. However, on the face of it, this about-turn did not really change anything. At the start of the 2000s, artist and entrepreneur Murakami Takashi put forward the theory that the so-called advent of a “new (or post-) Japonisme”, referring notably to the obsession for Japanese animated films that could be seen abroad, could prove hazardous. Despite the clever coining of the term “superflat” to describe the characters in traditional animated cartoons painted on celluloid, it was this rhetoric that was the main impetus for change —as well as the exhibition Coloriage, which he curated for the Cartier Foundation for Contemporary Art in Paris, in 2002. What, in fact, is the connection between the assumed naivety of Beat Takeshi’s paintings, the work of photographer Shinoyama Kishin, the giant plastic models of Doraemon or Gundam manufactured by the Kaiyodo company (named as “artist”), or the childlike delicacy of Taniuchi Rokuro’s drawings? The disquieting effect of this motley collection reveals the absurdity and cunning of the argument.

The movement that constituted Japonisme from the second half of the 19th century to the start of the 20th century, had at first been a creative meeting of minds between Japanese artists and their Western followers, of creators with fellow creators, and its widespread influence, whether through objects or more indirect means, was spontaneous and decisive. In this regard, apart from some recent examples of European productions (the films of Tomm Moore, Benjamin Renner and Rémi Chayé), the positive impact of Japanese animated film on the rest of the world can be judged by its reception by audiences. Though one needed to wait until some time in the future to evaluate this label properly, a closer look at Japanese animated film production reveals that, during the first half century of its history at least, it was a movement of opposing interests, which was trying, with a widespread and determined effort, to understand the direct and indirect issues presented by foreign animated films. Here are just a few examples.

Though Japanese experts agree that 1917 was the first time films were shown publically, there’s always a possibility that there are earlier films still to be discovered. One of the problems facing these historians is that films have gone missing. According to the National Film Centre, the proportion of Japanese films still in existence today dating from before 1923 is barely 4% of the the film production of the period. Among those rare films known to have survived, there was not a single animated film, until the discovery, in 2007, of two short animated films, one dating from 1917, the other from 1918. Up until then, the oldest surviving animated film in the country dated from 1924. Among the major film-producing nations – the exception being pioneers of cinema such as France or the United States – Japanese film production is characterized by being ahead of its time and by its scope. For example, in just one year, 1917, eighteen films produced by four cinema pioneers, and all shown at the same time, have so far been identified.

The enormous success of cinema in Japan right from the beginning immediately resulted in a profound interest in moving pictures, as evidenced by the many examples throughout the history of the graphic arts, such as the great success of mobile local magic lantern shows. From the start, the connection between Japanese animated film makers and their foreign counterparts was a fruitful one. During the whole of the first half of its existence, local artists, one generation after another, drew on this source of inspiration to enhance their own artistic efforts. In contrast to all other fields of endeavour – science, technology, art -, the reopening of Japan in the second half of the 19th century and had resulted in direct human contact (whether by sending Japanese students to the West or by inviting foreign teachers to come to Japan). For animation, the contact was mostly indirect and dependant on the few films that did arrive in the archipelago and were able to be studied by local film makers. From the outset, this distance from their role models gave Japanese pioneers a certain autonomy, a freedom to develop their own patterns of working.

This creative drive, this owning of a language, is already visible in The Blunt Sword (1917), the first film by Kouchi Jun’ichi, which demonstrates incredible skill in the use of cutouts and silhouettes, with its amazingly expressive faces, and the use of visual elements linked to the action (“visual onomatopoeia”, sounds appearing on the screen in speech bubbles)…

From 1927, Ofuji Noburo, one of Kouchi’s disciples, made animated films using silhouettes before discovering the work of Lotte Reiniger, which he studied closely. Darker and more tortured than their Western equivalents, Ofuji’s films such as The Spider’s Thread (1946), The Whale (1952) or The Phantom Ship (1956), sealed his reputation after the Second World War, notably at the Cannes and Venice film festivals. But his first film to be released, The Thief of Bagdad (1926), was already a tour de force, made using cutouts out of traditional Japanese paper called chiyogami. He freely borrowed from Raoul Walsh’s 1924 version of The Thief of Bagdad, transferring it into a Japanese context, skilfully combining elements of fantasy with stunning battle scenes.

Akagaki Genzo, the Farewell Drink (1924) is an instructive drama made with paper cutouts by Kimura Hakuzan, based on a famous story (Chûshingura) about 47 loyal retainers and their mission to avenge their feudal master. It was this film that freed Japanese animated film from the constraints of the cartoon genre, and allowed the portrayal of human beings as depicted in classical tragedy.

Having studied both traditional Japanese and Western painting, Masaoka made his debut as a self-taught animated film maker in 1930 with Monkey Island, a lively and fast-paced modernist manifesto using paper cutouts. A pioneer of talkies, he also employed the American technique of using celluloid, which his background in Japanese and Western painting allowed him to assimilate better than others. Throughout the 1930s, the skill of his team increased. Made at the height of the Pacific War, and escaping the censure of the army (which financed and regulated cinema for propaganda purposes at the time), The Spider and the Tulip (1943), marks a definitive turning point. This lyrical, pastoral animated operetta pointed to a new way for Japanese animated films that used celluloid. Freed from the limitations of the cartoon, it was able to be both visually poetic and to depict movement, characters and natural elements subtly and in fine detail.

But it was immediately post-war that Masaoka made his true masterpiece. Consisting of a few pastoral scenes, with no story or words, Cherry Blossom – Spring’s Fantasy (1946) is a quest for beauty, and probably the first time that a human figure was not represented as a caricature in a Japanese animated film on celluloid. In this lengthy movement of appropriation, during the period from the end of the Second World War until today, the role of Takahata Isao appears to be the most decisive, coherent and highly developed. More than anyone else, he transformed the language of Japanese animated film after the war, dismissing the conventions of the cartoon as “Disney style”. He concentrated on social and political aspects, and had a remarkable ability to reveal reality, the human figure and the beauty of everyday life.

The important elements of his aesthetic style were evident from his debut with The Little Norse Prince (1968), and imbued the whole of his film-making career, including the exuberance of the two Panda! Go Panda! (1972, 1973), the lavishness of The Tale of Princess Kaguya (2013), the truculence of Chie the Brat (1981), the musical finesse of Gauche, the Cellist (1982),the naturalism and tragedy of Grave of the Fireflies (1988), the subtle nostalgia of Only yesterday (1991), the picaresque shape-changer Pom Poko (1994), or the visually and narratively episodic My Neighbours the yamadas (1999)… His yearly television series, Heidi, Girl of the Alps (1974), Marco (1976) and Anne of Green Gables (1979) are still considered to be unique masterpieces.

With his keen interest in painting, architecture, music and poetry, Takahata never ceased to innovate, while his love for the graphic arts enhanced his film-making, allowing him in his own inimitable way to pursue his passionate discourse, which radiates through his work, across the years and beyond national borders.

ILAN NGUYÊN