A great admirer of Tsuge Yoshiharu, Asakawa Mitsuhiro worked hard to ensure his work was finally published in its entirety in the West.

An expert on mangaka, Asakawa Mitsuhiro talks about his ties to Tsuge and his views on his work.

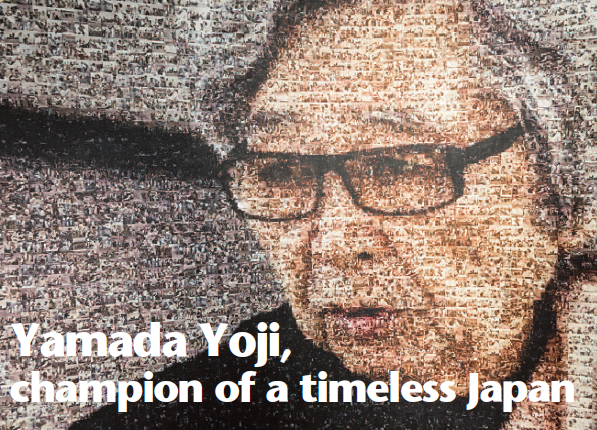

Few people know Tsuge Yoshiharu’s work better than Asakawa Mitsuhiro, the former editor of Garo who, in 1998, was among the founders of AX, another influential alternative manga magazine. Asakawa has researched Japanese comics for the last 30 years. Nowadays, he edits gekiga books (Tatsumi Yoshihiro’s “A Drifting Life”, Katsumata Susumu’s “Red Snow”, Tsuge Tadao’s “Tale of the Beast”, etc.), and manages the international rights for these authors. A diehard fan of Tsuge, he has an intimate knowledge of his work and is one of the few people who nowadays has free access to the elderly artist. He was kind enough to meet me during my Tsuge-related trip to Chiba Prefecture.

Why did you move to Ohara? It’s pretty far from central Tokyo. Isn’t it a little inconvenient?

ASAkAWAMitsuhiro: Last summer, I decided to move after living in Tokyo for 30 years. Five years ago, I left my job in publishing and focused instead on selling vintage audio equipment online, which is something I can do anywhere because I don’t need to commute to an office. I was looking for a bigger place, and found this old house in Ohara. As you know, both this town and nearby places such as Otaki and Futomi are very important in Tsuge’s life and work, so I leapt at the opportunity to move here. Other Garo-related artists live or used to live in Chiba (Shirato Sanpei, Tsuge’s brother Tadao), so this prefecture is quite important in the history of alternative comics in Japan.

You told me earlier that it took you ten years to convince Tsuge to allow the translation of his manga. Why was Tsuge against publishing his work abroad for so many years?

A. M.: You see, Tsuge has always tried to avoid whatever he found troublesome, annoying. In this case, for example, the tedious work of comparing the original Japanese text and the translations, looking for discrepancies, etc. He knew he had to do all these things himself, and he found them too much of a bother. For most of his life, Tsuge was a very anxious person, endlessly haunted by his inner ghosts. But now he seems to have reached a stage in his life when he’s at peace with himself and the world.

Is that why he finally gave his approval?

A. M.: Yes, he’s 81 now, and as I said, he’s stopped worrying about many things and finally takes life in his stride. Anxiety is related to fear of the future. However, at his age, Tsuge knows that he only has a short time left to live. His current life may be boring and repetitive (shopping for groceries, cooking three meals a day, etc.) but its banality makes it feel safe, reassuring. It also helps that his son is taking care of most of the business side of things. I often see him to discuss their deals with foreign publishers.

Let’s talk a little bit about you. I’m sure you’ve been a fan of comics since you were a child. Did you have any favourite titles or authors?

A. M.: My generation was more into anime than manga. For example, I used to watch Shirato Sanpei’s “Sasuke” on TV. But my favourite series was Mizuki Shigeru’s “GeGeGe no Kitaro”. I liked the fact that Kitaro was neither a human being nor a ghost. He was a yokai and followed rules and customs that were different from human society. I guess I was attracted to this freedom, this way of looking at things differently, which is also an important feature in Tsuge’s life and work. As a child who had a hard time conforming to school life and the accepted social customs, I was fascinated by Mizuki’s stories.

A new series is on TV right now, on Sundays. Do you watch it?

A. M.: It airs at 9:00, right? Nah, it’s too early for me. I usually work all night and go to bed around 6:00, so I’m afraid I’m still sleeping at that time (laughs).

Of course your favourite manga author is Tsuge Yoshiharu. When was your first encounter with his work?

A. M.: I think I was about 15 or 16. I read an interview with popular SF writer Tsutsui Yasutaka [“The Girl Who Leapt Through Time”, “Paprika”] in which he said that Tsuge’s “Nejishiki” had been a great influence on his work. So I decided to check it out.

And what was your reaction when you read it?

A. M.: “Neji-shiki” first came out in 1968, but I only read it much later, in 1980 or 81. Before reading Tsuge, I had found many parodies and references to this story in other comics without actually knowing the original. So when I finally read it, I understood where all those previous references came from. Anyway, I must say that while I was impressed by the novelty of “Nejishiki”, it wasn’t my favourite comic in the anthology I bought. I liked his travel stories better. When you think about it, “Neji-shiki” is a collage of many unrelated episodes rather than one coherent story. Scholars and fans have spent hours debating the story’s meaning and symbolism. Another book has just come out this year – The Secrets Behind Tsuge Yoshiharu’s “Neji-shiki” (laughs). But there are no secrets. It doesn’t really mean anything.

And when did you first meet Tsuge?

A. M.: I was introduced by Takano Shinzo. My university major was in art theory and I had written a thesis on Tsuge. Takano helped me with my dissertation, and it was thanks to him that I finally met Tsuge around 1991. For me, it was a pretty emotional encounter. You must understand that Tsuge is by far my favourite artist, so actually being able to meet him was a dream come true.

You’ve read and studied the whole of Tsuge’s work. In your opinion, what makes it stand out? What’s so special about his comics?

A. M.: Since the very beginning of his career, Tsuge has always been searching for a new approach to story-telling. As a child who grew up during the war, he was both exposed to Japanese imperialism and American-style postwar democracy. He was seven or eight when the war ended, and was certainly affected by this ideological and social change. As for his comic art, like all artists of his generation, he was deeply influenced by Tezuka Osamu. On top of that, when he began to draw his stories, he was exposed to the work of Osaka artist Tatsumi Yoshihiro, who coined the term gekiga for his dark, serious tales. Tsuge borrowed Tatsumi’s style and content and adapted them to his own personal vision. It was a slow process, which eventually began to bear truly original fruits in the second half of the 1960s when he joined Garo. When you analyse his approach to composition, you can see that he blew up the traditional structure (introduction, development, turn and conclusion) by introducing new ways of thinking about story-telling. Many of his comics, for example, end without a resolution; they are open ended. This causes the story to linger inside the readers’ minds. They keep thinking about it: where does the story go? What happens to the character?

It’s a very risky way to tell a story, isn’t it? If not done well, it leaves the readers baffled and disappointed.

A. M.: As a matter of fact, Tsuge’s stories are by no means easy to understand and enjoy. Not everybody is a fan of his comics. You either love him or hate him. On the plus side, even the stories he wrote 40 or 50 years ago don’t age. Even today, they feel modern, thought-provoking. I’m sure the foreign readers who are going to read them for the first time translated into French or English will not experience them as mere relics from the past.

Tsuge is said to have pioneered a comic version of the so-called “I-novel” (a type of Japanese confessional literature).

A. M.: He was a big fan of authors such as Dazai Osamu and Kawasaki Chotaro, whom he was already reading when he began to draw comics. The I-novel is neither an essay nor a diary and yet it contains elements of both. I think these characteristics appealed to Tsuge, and he sought to apply them to his storytelling. Many of his manga since the mid-60s – starting with “Chiko” – contain autobiographical elements though they remain works of fiction. Tatsumi’s gekiga were another important influence on him since his work avoided typical comic plots (suspense, adventure, mystery, etc.), instead featuring the everyday life of common people.

You mentioned kawasaki, whom I didn’t know until he was mentioned in one of Tsuge’s travel essays. They seem to share a few similarities.

A. M.: Indeed, Kawasaki was very poor and led a lonely life. Yet he doggedly pursued his writing career. Even his stories, while often focusing on people who are having a hard time, are never particularly dark or depressing. He actually had a great sense of humour. For many years his novels were far from popular. Actually it was Tsuge who spread the word about him in the late 80s. It was thanks to him that his books began to sell. Among I-novel authors of that period, he’s probably the only writer who is still highly regarded.

How do you see Tsuge’s legacy today?

A. M.: Notwithstanding his many efforts to “disappear,” to “become invisible”, he’s undoubtedly had a great influence on both his contemporaries and the younger generation. As a comic artist, I’d say he has been more influential than people like Mizuki or Shirato. And his stories have the potential to appeal to readers everywhere for many years to come.

INTERVIEW BY JEAN DEROME