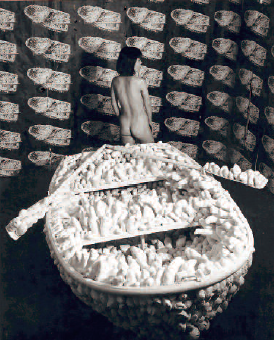

© Yayoi Kusama and © Yayoi Kusama Studios Inc.

A retrospective exhibition dedicated to the 83-year-old artist allows us to grasp both the diversity and the radicalism of her art.

Upon arriving to Miyanoura harbour, on the island of Naoshima, the first thing that you notice is a gigantic red pumpkin covered in black spots. Signed by KUSAMA Yayoi, this piece of art has become one of the symbols of this island that has been turned into a contemporary art centre. The artist left another one of her pumpkins – yellow this time – next to the Benesse House, as a reminder to the visitor of her obsession with dots, present in many of her works. She, who now lives in a “psychiatric hotel”, is often considered close to crazy. But that’s far from being the case. The retrospective that the Tate Modern dedicates to her corrects this reductive way of presenting her. “I saw my first dots when I was ten, and I still see them today” says the artist born in 1929, who was trained at the Kyôto art school, despite a family that was little inclined to understanding her enthusiasm for painting.

After the war, Japan’s defeat and Hiroshima and Nagasaki’s nuclear bombing, like many other artists, the young woman was strongly influenced by the show that nuclear fire left behind. Before scattering dots across her paintings, her works from that period are characterized by a heavy and deadly atmosphere. After being encouraged to move to New York by a psychiatrist, she disembarked there in 1957 and was soon to be noticed, what with her white and coloured monochromes, reminders of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Jones. Nobody before had ever been so devoted to them as she was, on gigantic canvases with the same brush movements repeated infinitely, as if she were trying to reach the void.

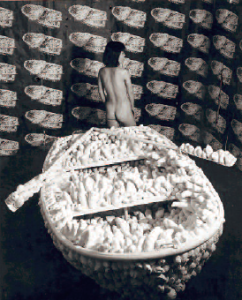

Her works then evolved to focus on the use of objects of consumption, opening the way for other artists to dig down that path. She continued with her dots, and explained that her “life is a lost dot amongst thousands of other dots”. That inspired her funny-looking wood structures, covered with mirrors and sheltering large balloons filled with helium, between floors and ceilings covered with coloured discs. The environments she creates are altogether enveloping, enchanting and frightening. In New York, she was part of the dissenting movements in the 60s. She organised happenings in which young women and men, as well as herself, walked around naked with big coloured dots painted on their bodies, forming a joyous fray or walking through the streets. Tired of all the agitation, she returned to Japan and buried herself into her work again. Dark collages at first, then environments covered with mirrors in which little multi-coloured lights replace the dots: proof that Kusama Yayoi’s artwork cannot be reduced to dots.

The recurrence of the pattern must not get in the way of showing the great diversity of her artwork, which the Tate Modern’s retrospective shows with more recent pieces. By choosing to live in a psychiatric environment, the 83-year-old artist also plays with our will to interpret her peculiar work. But it doesn’t stop her from travelling to inaugurate her exhibitions, neither from working in her workshopevery day. She may thus go back to a more systematic use of dots in new “environments”. In a closed area, mirrors increase the number of dots infinitely around the visitor, such as with The Passing Winter (2005). You still have time to immerse yourself into this incomparable universe. Once more, the Tate Modern shows its capacity to honour artists whose work is characterised by extreme radicalism and obvious originality. And for those of you who can’t get enough of KUSAMA Yayoi’s art, and who are able to travel to Japan, you may be interested to know that hundred of her more recent pieces are currently being shown at Saitama’s Modern Art Museum, North of Tôkyô. This exhibition goes on until the 20th of May.

Gabriel Bernard