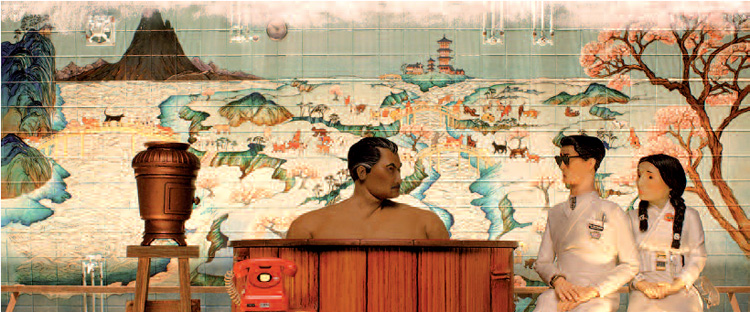

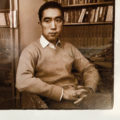

Mayor Kobayashi is the spitting image of Mifune Toshiro, Kurosawa’s favourite actor, in High and Low (Tengoku to Jigoku, 1963)

A winner at the Berlinale, Isle of Dogs illustrates the extent to which the American film-maker has penetrated the Japanese soul.

At first glance Isle of Dogs, Wes Anderson’s latest film, would appear to be yet another attempt by a foreign film director to uncover the mysteries of the Japanese soul. Others before him have sought to “understand” Japan in the hope that it might seem less exotic, but in most cases, the results have been unconvincing, often reinforcing our prejudices about the country and its inhabitants who “are not people like us”, as a famous French humorist wrote ironically. In choosing to produce a stop-motion animated film rather than a live-action film, the film-maker avoided one of the pitfalls of foreign films shot in Japan, which are always set in the same places – Shinjuku, Shibuya, Harajuku – so clichéd that one always ends up asking oneself if the film-makers have ever set foot outside the capital.

Wes Anderson preferred to set his story in the middle of a completely original urban world called Megasaki, in the relatively near future, which allowed him to give his active imagination free reign, and let him introduce dozens of historical references from the past and the present as the story unfolded, without any of it appearing incongruous. This is what makes it a great film about Japan, and from it one can learn a lot about the Japanese way of thinking. When asked what prompted him to embark on the project, the director at once admits his interest in dogs, the future, rubbish dumps, childhood adventures, and Japanese cinema. “I tried to make a film that was a bit futuristic. I wanted to film a pack of dominant males who might all be leaders of the group, surrounded by a world of rubbish. We chose to locate the story in Japan because I’m steeped in its cinematography. I love this country, and wanted to work on a project directly inspired by Japanese cinema, with the result that it ended up being a synthesis of a film about dogs and Japanese cinema,” he says.

There are many glimpses of Japan’s seventh art. Kurosawa Akira is the first name that springs to mind, as one of the main characters in the film is the spitting image of Mifune Toshiro, Kurosawa’s favourite actor, in High and Low (Tengoku to Jigoku, 1963), and because the ever-present world of rubbish in Isle of Dogs in some respects recalls the sets in Dodes’ka-den (Dodesukaden, 1970). But there are also references to Ozu Yasujiro, and to monster films, one of the great masters of which was Honda Ishiro. All this let him create the perfect framework for his story about dogs banished to an island used as a rubbish dump, following the outbreak of a dog-flu epidemic. But a stubborn young boy, Atari, who arrives in search of his dog Spots, despite a ban on travelling to the island, plays an important role in the discovery of a farreaching conspiracy aimed at imposing a form of dictatorship on Megasaki.

When Wes Anderson says it is his most ambitious film, one can only agree with his opinion, because Isle of Dogs is a good illustration of the courage he displays in his film making, in as much as he is not content just to recount an astonishing story. He has conceived a coherent world, in which the development of the characters fits in harmoniously with the film’s intention. Because behind the entertainment and some of its comic aspects, the film tackles more serious subjects related to the evolution of our modern society. These are certainly not specific to Japan, but this country is often the first in line to confront problems thrown up by the developments in our industrialised world. The futuristic settings include numerous elements from the 1960s, a pivotal period in contemporary Japanese history with its uncontrolled industrialisation and pollution, a time also of young people protesting, and are perfectly adapted to the thrust of the film. The influence of great names from Japanese cinema is very evident, and one is delighted to find echoes of Suzuki Seijun’s work in certain scenes that take place in the imaginary city of Megasaki. In this excellent film, the recipient of The Golden Bear award for best director at the Berlin Film Festival, it’s pleasing to discover that Wes Anderson has not fallen into the trap of producing a clichéd film about Japan. In particular, he owes much to the work of Nomura Kunichi, one of his co-scriptwriters. “We have all been friends with Kun for a good many years, and it was thanks to him that the details were so authentic and the film had a real Japanese feel to it, given the fact that none of the rest of us who were writing the story was Japanese,” recalls the film-maker. The film takes a really incisive look at Japan. The film never gives the impression of being just “a taste of Japan”. On the contrary, this film is Japanese in tone and in the way the different characters interact with each other. The only one who behaves differently is Tracy Walker, the American high-school student on a language exchange visit, who writes enthusiastically for the school magazine and pits herself against the mayor, Kobayashi. Despite her wish to fit in, she retains the mannerisms of a gaijin (foreigner). When, for example, she wants to write something on the basis of her “hunch”, the editor- in-chief replies: “I’ll never publish anything based on a hunch”. This is completely characteristic of journalists in Japan, who only rely on repeatedly corroborated facts when writing their articles. These are the kinds of details that make Isle of Dogs a Japanese film. And if you add to that the humanist dimension that emerges, which is without doubt directly inspired by the films of Kurosawa Akira, one can only be thankful to be in a position to enjoy a film of such intensity. For all these reasons, we’re prepared to say that this is the best “Japanese” film of the year so far.

ODAIRA NAMIHEI

Leave a Reply