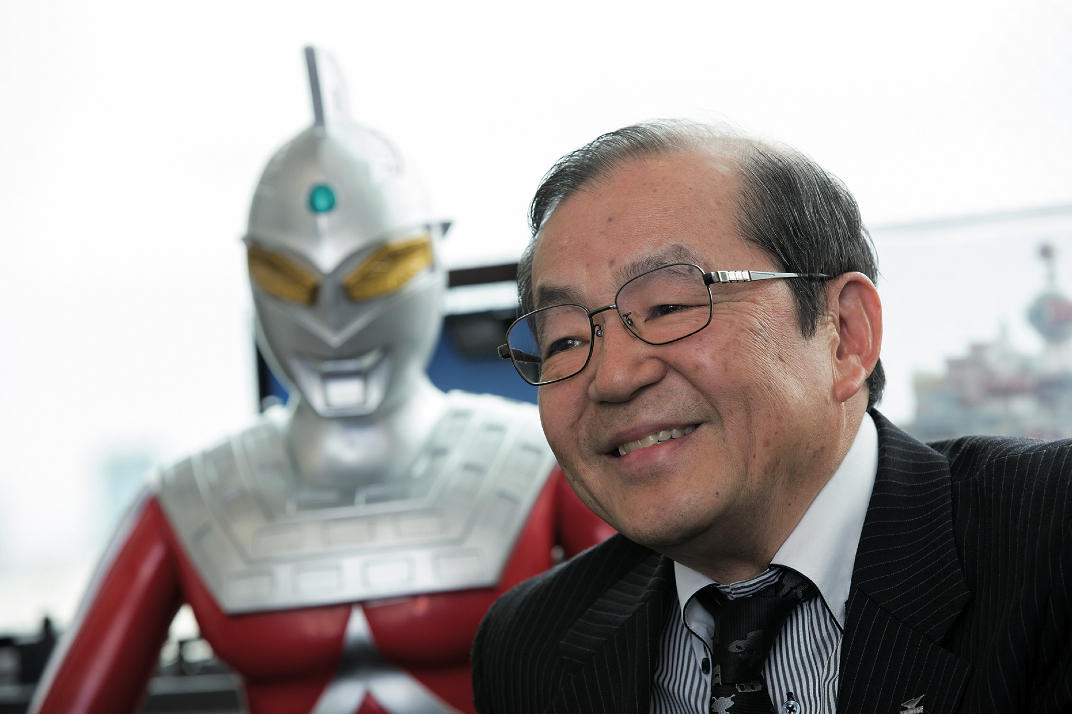

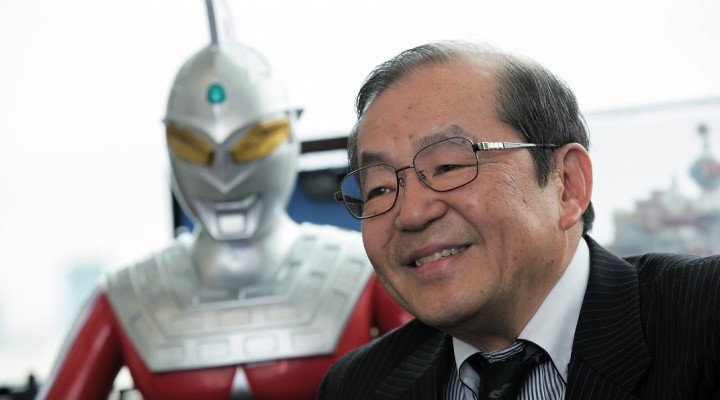

President of Tsuburaya Productions, Ooka Shinichi looks back on his career and the incredible longevity of his superhero.

Though most movie fans are interested only in the people who appear in front of the camera, film making is very much a team effort and the invisible crew working in the background plays an essential part in a title’s success. For many years, Ooka Shinichi was one of the cameramen who gave Ultraman its distinctive look, both on the big and small screens. Since 2004, Ooka has been involved in the production of many television series, and in 2008 he became Tsuburaya Production’s president. We met him in his Shibuya office to talk about the saga’s past, present and future.

It appears that you were meant to be a lawyer.

OOka Shinichi: Well, it’s true I enrolled in Keio University’s Faculty of Law. Unfortunately, those were the years of student protests around the world. In this country in particular, people were opposed to the United States-Japan Security Treaty. Campuses were occupied and for a year all academic activity just stopped. I wasn’t very keen on studying in the first place, and spent the time mostly doing odd part-time jobs. So in 1969 I decided to quit college. I was interested in camera work and managed to get a job at Tsuburaya.

How did your family react to your decision?

O. S.: They didn’t like it at all, of course, but eventually they understood my feelings and let me have my way.

So you had already been playing with cameras?

O. S.: I had an 8mm camera and I used to make small movies, but until quitting college I had never thought to turn my hobby into a profession. Then, late one night, I was watching a film called Arashi (the tempest) on TV and I was struck by a particular scene. I can’t really explain what happened inside my head, but I suddenly decided I wanted to be able to shoot such beautiful scenes myself. You could say it was a sort of revelation.

Can you tell us about your beginnings as an assistant cinematographer? What was working at Tsuburaya Productions like in those days?

O. S.: I actually wanted to work for Toho, which was a much bigger company, but at the time they were not hiring so I was sent to Tsuburaya, which was a sort of subsidiary company. They had already done Ultra Q, Ultraman and Ultra Seven. All of them had been big hits with TV audiences, but at the same time had stretched the company’s resources. Consequently, at the time I was hired they were not working on any projects. Anyway, even though I thought I had a gift for photography, I had no previous training, so I had to learn everything on the job, which meant starting from the very bottom. Of course, they wouldn’t even let me touch the cameras. So in the beginning, all I did was polish the tripods (laughs). They wouldn’t even teach me the basics of camera work; all I could do was to watch and learn from them. For many occupations in Japan, this is how an apprentice starts to get acquainted with the trade of his choice.

How long did you have to wait before you could actually put your hands on a camera?

O. S.: Three months after being hired I was assigned to a new TV program called Unbalance. It was a series of horror stories, each one written and directed by different people. That’s when I began to work as a third-assistant cinematographer.

Were you happy about working for a company that had become famous for its tokusatsu (special effects) work?

O. S.: To tell you the whole truth, in the beginning I wasn’t really interested in special effects or superheroes; I much preferred to work on literary adaptations. In fact, in the three years I was a fulltime employee at Tsuburaya, I spent very little time on a tokusatsu set. Even when I worked on The Return of Ultraman in 1971-72, I was in the other studio, shooting the non-SFX scenes. That was a particularly happy experience because I was finally promoted to first-assistant, and I got married during the same period. A few years later, in the early 1970s, I did begin to do tokusatsu work, like Ultraman Taro, Iron King and Super Robot Red Baron, but as a freelance cinematographer.

I guess making tokusatsu films in those years must have been quite a challenge.

O. S.: Yes, of course. As I said, I didn’t have any direct experience in the 1960s, but I heard a lot of stories from other crew members. As you can imagine, when the first series was created the working conditions were rough, to say the least. Of course, there was no air conditioning inside the studios, so it was freezing cold in winter and scorching hot in summer. You could say they were doing their jobs in appalling working conditions. It was hard, dirty work, and most of the crew tried to avoid working on tokusatsu sets. Everybody wanted to shoot cute young girls and famous actors. Also, many people at the time looked down on TV productions. For a cameraman, working on a feature film was the ultimate goal.

Why did you quit Tsuburaya in 1972?

O. S.: It was nothing special really, but as I said, I had just become first-assistant cameraman and suddenly I was asked to work on a new project as a second-assistant. It felt like being demoted. It wasn’t all that unusual actually, in that kind of studio system, but I took it badly and decided to quit. Thinking back now, I believe it was a good decision on my part because it gave me a chance to do many kinds of projects and work with some great people. I got to know famous cinematographer Okazaki Kozo, for example, and I learned so much from him. We had a very good relationship that lasted until he died about ten years ago. Thanks to him I was much more polished and confident when I later did more tokusatsu work for Tsuburaya as a freelancer. And then I finally came back to Tsuburaya about 30 years later, around 2003 or 2004.

The Ultraman series is still going strong after 50 years. Why do you think people are so fascinated with this superhero?

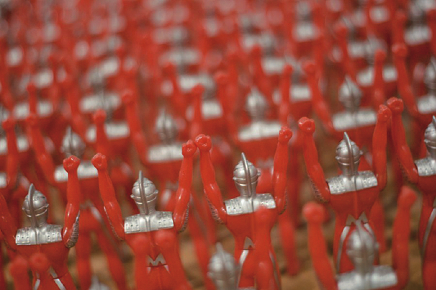

O. S.: When Ultraman first appeared 50 years ago, it had a tremendous impact on TV viewers. They had literally never seen anything like that. In a sense, it was a double debut because, although the original Ultraman series was shot in colour, very few people had a colour TV, so they watched it in black and white. Then a couple of years later there was a colour TV boom and the broadcaster decided to rerun the 1966 series. These people (the age of our target audience was elementary school kids) developed such a strong attachment to Ultraman that they later passed it on to their children and grandchildren. So now you have three generations of TV viewers who share the same interest. This is far from common.

How has the franchise changed content-wise during the past 50 years? How has Ultraman adapted to a changing society?

O. S.: On one hand, Ultraman’s core themes and ideas haven’t really changed in 50 years. The individual series may differ in their details, but the basic values of justice, courage and perseverance have always been there. When kids watch the show they may not really be conscious of that, but growing up they realize what Ultraman stands for. On the other hand though, the way you tell a story now is very different from 10 or 20 years ago, let alone 50 years ago. So we have to adapt to the different social and cultural environment, which doesn’t just mean pandering to people’s changing tastes. After the the disaster on the 11th of March 2011 for example, our sense of values has changed considerably, and we have to take that into account when we work on a new series.

Is it true you are tired of being “only” Tsuburaya’s President and are planning to get back behind a camera?

O. S.: Well, I’ve said it so many times it’s become a joke. Nobody takes me seriously here (laughs)! But yes, if it was all up to me, I’d like to work on one more film. It’s just so much fun!

INTERVIEW BY JEAN DEROME

Leave a Reply