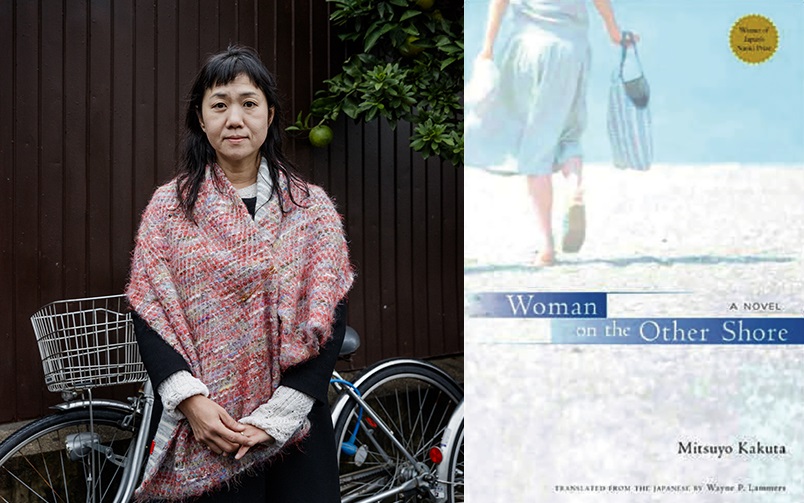

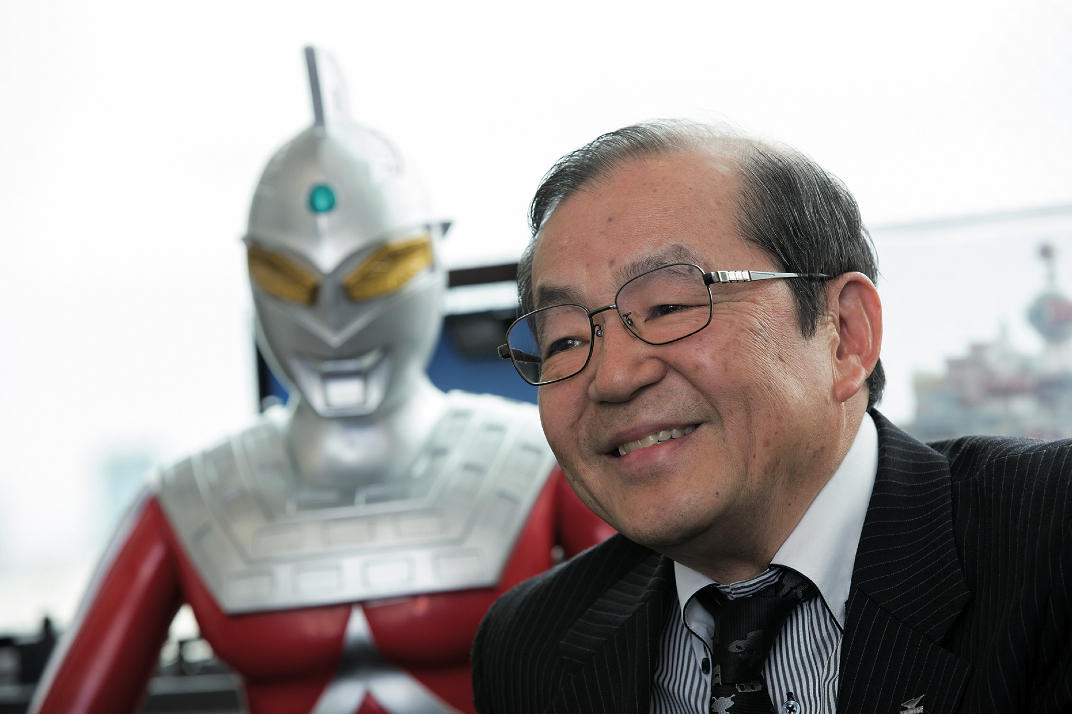

The author Yu miri, as someone who had nowhere to go herself, has continued writing for people in the same situation.

In 2018, two translations of author Yu Miri’s works will be released in the U.K. Living a mere 23km from the troubled nuclear plant in Fukushima prefecture, what does Miri see now, what does she think about and what does she choose to put into her writing? We went to talk to her when she recently visited England to appear on a talk show.

You were originally an actress in the Tokyo Kid Brothers theatre group before you start writing. Could you please tell us what first got you interested in the world of theatre?

YU Miri : In actual fact I did not really get to choose what I wanted to do in life from lots of different options. When I was in primary school I took the exams to go up to middle school and managed to get in but… I just could not get comfortable or fit in there. It was the atmosphere of the place, or perhaps just the idea of learning things at school that did not sit with me. I flatly refused to attend school and even started going to a psychiatrist. I did go on to sixth form but I stopped attending and ultimately was expelled. After that I was pretty much kept under house arrest from my mother, though that was because I had already run away from home and tried to commit suicide several times, so they really could not let me go out. We pushed each other to our limits psychologically, resulting in my mother standing by my bedside at midnight gripping a kitchen knife and other dark episodes. Once she said she wanted to talk with me outside and I got on the back of her motorbike, but she tried to take us both crashing into the sea. It was an extreme situation where she was trying to kill me and to die herself in the process. So I really wanted to get out of that house. I didn’t care where, I wanted to leave, whatever it took.

And so that is how you joined the Tokyo Kid Brothers theatre group?

Y. M. : Yes. It was by a kind of chance that I wound up with that particular troupe. I had snuck out while my mother was sleeping and went to Harajuku in Tokyo where they just happened to be performing a play. I was 16 when I joined the troupe but that was not like there were many paths I could have taken up until that point and I chose it because I particularly liked it or because I felt I was good at it. As I had been expelled from the sixth form, my education history ended with secondary school, so even most low-level part time jobs were pretty much impossible for me to get into. With such a severe lack of options, I chose the path of the theatre because education was not relevant there.

But don’t you think that you must have been able to continue doing it and to become as famous as you have because it suited you?

Y. M. : Hmm… I don’t really feel that I was suited to it, no. Since I was in secondary school I felt like I was always living right on the brink and that I would have fallen hard if I took even half a step the wrong way, both at home and at school. Writing was in some ways a final thing for me to cling to the last narrow platform, only just big enough to hold my size 5 feet, on which I could still stand.

So why did you turn to writing novels?

Y. M. : I had been writing plays for a long time, ten plays and even won the Kishida Kunio theatrical prize, but with plays you go through a long creative process where you write the script and then hand it over to the producer/ director and it is performed by the players. I gradually started to feel that I wanted to get away from having the final result of my art influenced by the quality of the production and express what I had written more directly to the reader in a more personal, one on one relationship. Then I started, continued writing novels and am still doing it to this day, but in my own mind I have not actually stopped writing plays though. I think I feel like writing another play some time soon.

What kind of play do you want to write now?

Y. M. : I am currently living in Minami Soma, in Fukushima prefecture and working on the radio, doing some slightly special broadcasts for the temporary emergency radio station. It is a radio station that broadcasts when there are major disasters that cut of regular communications channels, things like tidal waves, earthquakes, floods, typhoons or large scale fires, providing useful information like where emergency food or water is being distributed etc. So it is not going all the time but only broadcasts while the effects of disasters are being felt. Minami Soma was close to where the nuclear power station meltdown occurred, and many people are still living in temporary accommodation here. The population of the city was over 70,000 before the disasters struck but today, with next March marking six years since then, it is effectively only 50,000. Obviously some of the people have died, but a lot of them evacuated outside of the city and are even now still living as refugees. So amongst all that, the 30 minute program that I present once a week is about listening to the stories of the local people, inviting two people to talk together every time. We have all kinds of combinations, from husbands and wives, pairs of friends, students and teachers to couples, work colleagues, siblings, even shopkeepers and their customers. We have heard from a total of 420 people since we started doing the show. And while I was doing this, I wondered if I could somehow create a play with these people. These people have suffered greatly by the Great Tohoku Disaster, and continue to suffer today. They are also a passive party in the sense that they are receiving aid, so I thought that it would be good if I could help these people say something proactively with their own voices. I want to use regular, everyday local people to play the roles, rather than professional actors. The dialogue too, will not be in national standard Japanese but use the local dialect.

I think that you are often seen by people as an author who actually lives in Minami Soma and commits to social and political problems, but do you actually think in that way yourself?

Y. M. : I don’t do this because I want to commit politically. The power station where the accident happened is being called the “Fukushima” nuclear plant, but in actual fact it was a power plant run by Tokyo Power Company and the electricity generated there was not used by the people of Fukushima but entirely by those in the capital city region. When I started thinking in that way, it no longer seemed like this thing that happened in faraway Fukushima. I started to be aware that, as someone who had lived her whole life in the capital, I was equally culpable in this.

Why did you decide to move to the area then?

Why did you decide to move to the area then?

Y. M. : Through listening to the stories of those 420 people as I was doing my job for the radio, I came to know the hardship in their daily lives. Not so much the radiation issues, but more to do with issues affecting the local economy. The region is mainly agricultural and the disaster made it impossible to continue farming. Even if the caesium tests came back clean people would still not buy the local produce. There were even those amongst the dairy and other farmers who were driven to suicide. Moreover in the coastal regions of Fukushima it is quite different to the cities in that a lot of families live together with two or three generations. So you have these really massive plots of land with what are essentially small hamlets on them, with the main complex, an annexe, a house where elderly relatives would live called an “inkyo”, a storehouse, arable and paddy fields and patches of woodland. An extended family and all the relatives would be packed in living there, and the bonds within them are incredibly strong. To give an example, you could see a child in a household breastfeeding from his mother and then run off in glee to the next house where the mother there will also feed him, things like that. Another thing is that there is this local delicacy in Soma called “hokki gohan”(Lit: “Sakhalin clams rice”), made by frying clams into the rice. So sometimes a household are having hokki gohan, but they might say “I would like some white rice tonight too” and just pop to the household next door to borrow some. Or someone could be walking along and see that the carrots growing outside one of the other houses are looking really well and decide to borrow some to make curry that evening. You can see their really strong community dynamics, completely different to what you find in the big cities. But as a result of the nuclear disaster you often saw just the younger generations evacuating to other prefectures with their children and leaving the elderly relatives behind. That splitting up of extended families was a very big thing. I thought that if I were to carry on living there in the safety of Kamakura and just commute here then I would perhaps not be able to understand these hardships that people face in their daily lives. That is why I moved to Minami Soma.

It is now about 20 years since you received the Akutagawa prize in 1997. Do you feel that your own writing style has changed over those 20 years?

Y. M. : I have never actually read through anything I have written. To get a novel published you have to read your book through so many times in the process, but I decided that I would not read anything that has already been made into a book as I believe it is no longer really mine and becomes a story that belongs to the readers. So I think that it is not my job to comment on the structure or flow of my works, or how they have changed in that way. However, one thing that I can say is that I now find myself interested in and wanting to write novels that shine a spotlight on peoples everyday lives, which is something I was not interested in at all when I was younger and in my 20s.

In “JR ueno Eki Koenguchi” (JR Station Park Exit) that is going to be published in the u.K., why did you decide to write about homeless people?

Y. M. : I started writing novels at age 18 and I am now 48, so that makes it pretty much exactly 30 years. In the interviews I have done over those years, one of the questions I am asked most is “What do you write for?”, and I have consistently answered this with “I write for people who have nowhere to go”. I continue to do so because my feelings have simply not changed. It goes back to why I started writing in the first place; because there was nowhere for me in this reality at home or at school, I started writing and creating another world. So I really want to write about those who have nowhere of their own; homeless people and those whose homes were polluted so badly by the nuclear accident that they could not return. I cannot rest without writing about these kinds of people.

Do you think that your latest book published in Japan, “Neko no Ouchi” (The Cat’s Home), is a tale that came from your experiences after you moved to Fukushima?

Y. M. : I think so. To sum it up succinctly, I feel that there is always a path to escape from despair in life. While living in Minami Soma, what I have really noticed most is how diligently everyone is living their own lives. There is a little shopping street nearby my house, and whether they are shoe shops, clothes shops, tailors, butchers, florists or fishmongers, they are all businesses that are run entirely by family members. And just looking at these shops you can see that none of them are massive successes, they are not making much money. But the shopkeepers are all so diligent in the way they do their jobs. For example, if you take the cobbler to fix a heel that has frayed off your shoe, this cobbler actually sews it back together for you and not just glues a patch over it. I also once asked the tailor to re-stitch a traditional kimono that I had and make it into an evening dress, but they don’t charge all that much for the service. And the fishmongers too. Sashimi is usually all pre-cut and wrapped up for sale, but here in Minami Soma, when tea time comes around the people all line up outside the fishmongers holding plates. The customers will ask for a little more tuna or a bit of extra bonito, and the fishmonger will cut it up and put it on the plate right there in front of them! And it’s cheap too! I actually had that fishmonger on my radio show and I asked him if it was hard doing all that, but he responded that he could not cut corners because all his customers have come to appreciate the difference. Everyone here is living so diligently like that, everyone is living together in a tight community and helping each other out. So if you ask me then I get angry that these people living in a manner so far removed from cynical economic concerns are being so badly affected by a nuclear power station, an embodiment of the very pinnacle of those economic concerns. But at the same time, to see people like these, who are living this diligently and humbly in such great sadness and hardship when there were many who lost their lives or who are still missing, has touched me inside. That is why I depicted the scenes of everyday life in Neko no Ouchi in such a heartfelt manner.

Now, 5 years on, do you believe that events of March 2011 have changed the way that Japanese people live their lives?

Now, 5 years on, do you believe that events of March 2011 have changed the way that Japanese people live their lives?

Y. M. : I would say they have been forgotten. Immediately after the disasters there were a phenomenal number of mass media that flocked to Tohoku, then basically the media come to look for even more sad and harrowing images around the 11th of March each year. Journalists will ask people if anyone will let them photograph their houses and if someone responds “My home was not washed away by the wave” then they will just suck their teeth in disappointment. Even people’s terrible personal tragedies like this are simply a commodity for the media. What I always hear from the people in TV and newspaper journalism is that programs about earthquakes don’t get good ratings or that books about them don’t sell. Tokyo is now turning its eyes forward to the upcoming Olympics and getting excited about that. But at the same time, it is undeniable that there are many reconstruction projects that are not getting funding coming in, or that are being delayed due to the rise in the price of building materials caused by the Olympic preparations. Because of that, some of the victims of the disaster are still living out of temporary accommodation. In my radio programme one of the local people made an incredibly memorable comment after hearing the news that Tokyo had been selected for the next Olympics: “To the people of Tokyo, a mighty elephant, Minami Soma is like a tiny ant. So they don’t care if they stamp on us”. It is undeniable that the events of March 2011 have already been forgotten there and the local people are hurt by being forgotten, pretty much.

The Olympic Games are going to be held in Tokyo in 2020. Do you plan on writing anything to do with that?

Y. M. : My book “JR Ueno Eki Koenguchi” depicts the story of people from a very poor region of Tohoku who left their homes to work on preparing for the first Tokyo Olympics held just after the war, but who were used and discarded, ultimately becoming homeless. In the present day too, all the manual labourers on building sites across the entirety of Eastern Japan, including Tohoku, are being drawn away to the Olympic venue sites as the money is better there. Because of that there are no people working on the reconstruction and decontamination in Tohoku. Thus these sites are having to recruit from regions where wages are low, such as Nishinari in Osaka or from Okinawa, and that means that the people who do come are only one step away from homeless themselves; people who have no insurance, no family and who may already be ill. So in Minami Soma today you see these migrant labourers without insurance coming to the hospitals for consultations and then running away when the time comes to pay. There are also a lot of alcoholics and it is affecting public peace and safety. It is bad for the region but on the other hand I truly do feel sorry for the migrant workers themselves. Some of them even pass away while they are working, stung by wasps or having accidents on the building sites etc. When one of those people dies, nobody will come to collect their bones after cremation. There is a temple close to my home and you can see how the temples in Minami Soma have now become the final resting places for the bones of the poorest minimum wage migrant labourers from all across the nation. I want to write about this, a part of the reality of the Tokyo Olympics after all.

INTERVIEW BY SATOMI HARA

Leave a Reply