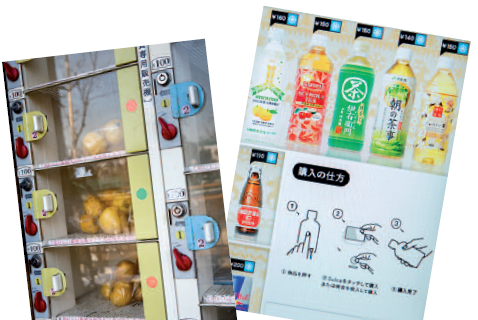

The Seibu Railway company published very nice posters to explain how to behave in the station.

How should you behave in Japan? A headache for some people, but all you have to do is look around you.

T o many foreign visitors, Japan is akin to an alien planet whose inhabitants follow strange rules and abide by different moral principles. The world wide web is full of forums where the most disparate actions are debated, assessed and often condemned as disgraceful faux-pas. Is Japan really such a mine- field? Or is it okay to behave as if we were in our own country, only being guided by our common sense? It’s a good question. One thing can be said for sure: human behaviour and social exchanges in Japan are characterised by a high degree of ritualism as they often involve precise etiquette and many unwritten rules.

Foreigners are usually not expected to know many of them, but it’s always better to stay on the safe side and avoid making a bad impression, so here’s a list (far from complete) of dos and don’ts and a few comments.

On the move

• Don’t eat or drink on the move, especially when riding on public transport. The one major exception is the shinkansen because it’s a long- distance train and the seats face in the same direction, with little chance of eye-to-eye contact. The famous ekiben (station bento boxes) have been created with these passengers in mind. You may see people eat an onigiri or a small bread roll on local trains as well if they are not crowded, or if they’re out in the countryside. as for eating and drinking while walking, there are generational differences in attitude. More and more young people do it, and in some commercial areas with lots of shops it’s done by everybody as a matter of course.

• Talking on the phone on a train, or even when walking in crowded areas, is one of those things on which everybody agrees: it’s just not done. It’s also one of the rare cases when the usually shy Japanese are going to stare at you disapprovingly or even tell you to shut up. Send an email or a text message instead. actually, any loud talking on a train is frowned upon. The only people who get away with it are certain middle-aged ladies – the much feared, obnoxious obatarian.

• a new addition to things to avoid on public transport is carrying your backpack on your back on crowded trains as you risk hitting those behind you.

Eating and drinking

• when eating out, it’s likely you’ll be handed an oshibori or wet towel to clean your hands. wiping your face with it is generally considered bad manners. However, you’ll see many Japanese men vigorously wiping their sweaty faces in summer (middle-aged guys are infamous for having questionable table manners), but you should refrain from doing it when you’re in the company of women: they dislike it intensely.

• Chopsticks are only made for eating, period. So waving them around, pointing them at other people or playing with them is definitely a big no-no. and do not stick them into rice: it’s only done at funerals.

• The Japanese pour alcohol into each other’s glasses when they see they’re empty.

• when dining in groups, the Japanese like to split the bill regardless of how much they’ve eaten or drunk. Therefore, insisting on only paying for what you’ve ordered is frowned upon. This is always a source of problem when my wife and I go out with friends because we don’t drink and end up paying for their booze.

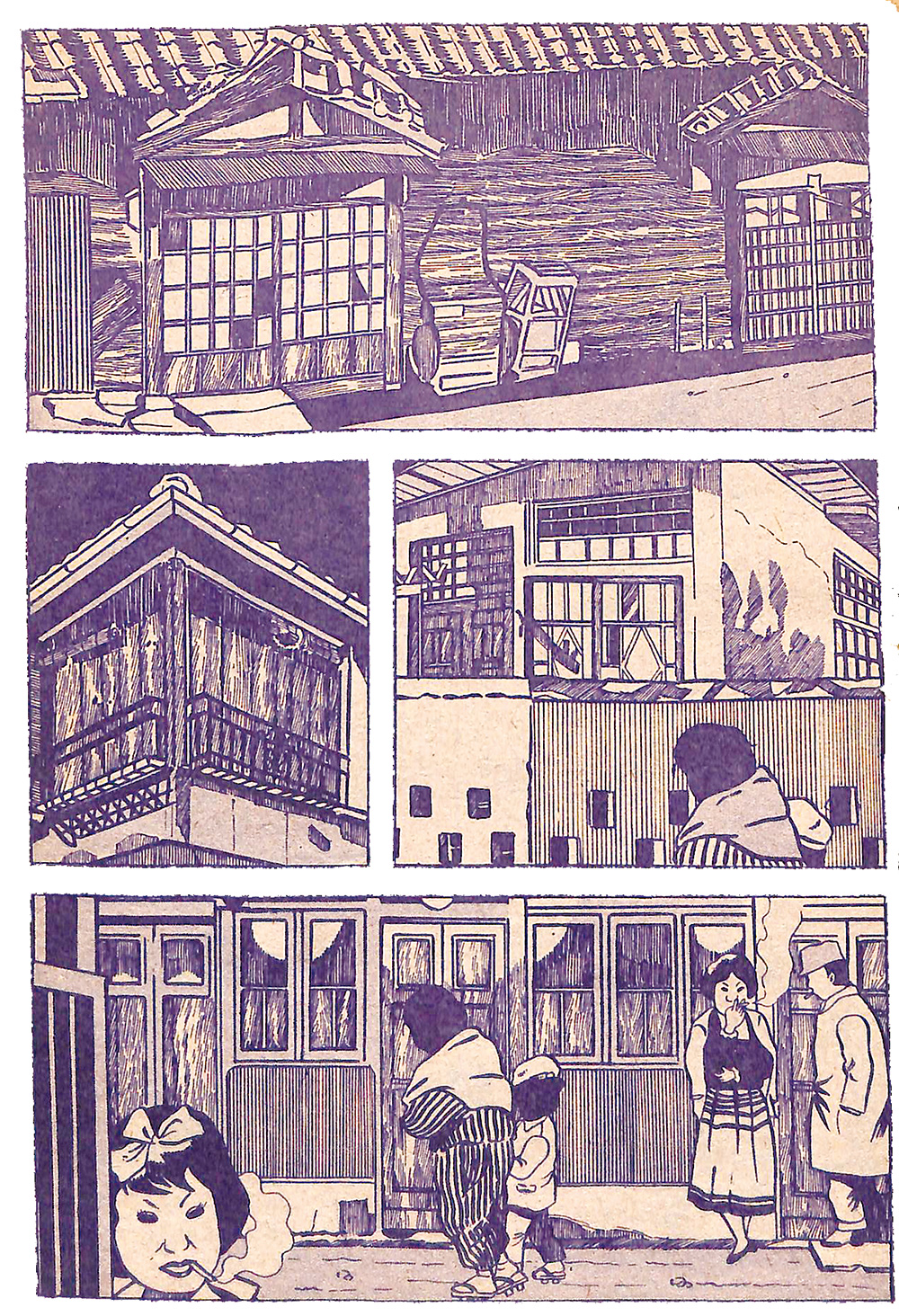

The campaign targeted Japanese and foreigners using famous ukiyo-e style.

smoking

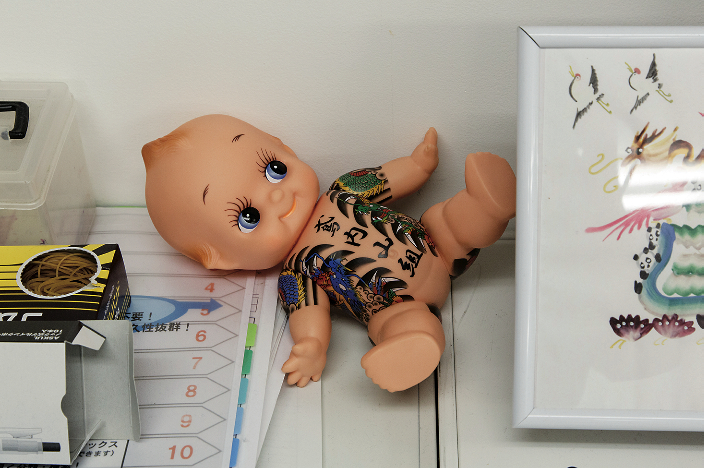

I used to hate people who smoked while walking because in Japan a lot of men carried their cigarette at knee height. It was dangerous, especially for children. Luckily, smoking outdoors is now prohibited except for a few designated areas. In- doors, it depends where you are. Some cafes and restaurants still have smoking areas.

Clothes

• as many people know, many places and all private houses require that you take off your shoes. while being invited to someone’s home is rare, you’ll often need to step in and out of your shoes at some museums, restaurants, traditional inns, etc., so it’s better to wear shoes that slip on and off easily.

• In traditional inns, you’ll be wearing a yukata or light cotton kimono. You should wear it with the left side over the right. The reverse is only for the dead at funerals. also, hairy men should always be careful to keep their yukata in place at the top. Nobody wants to see your hairy chest. They find body hair gross.

The rest

• at onsen (hot springs) and public baths, scrub your body thoroughly before entering the big communal pool, even if you’ve showered that morning. at the end, use the bucket provided to pour water over yourself. Keep your hair out of the bath. and, of course, do not swim!

• Don’t blow your nose in public. This is one of the more controversial rules because opinions seem to vary depending on whom you ask. For some people, if you need to blow your nose, you should go to a bathroom first, especially at a formal occasion. However, if you are with friends, it’s okay as long as you face away from other people and try to keep the noise down. It’s also true that in Japan many people keep sniffing in- stead of blowing their nose in public. If someone has a runny nose, it quickly becomes annoying. The only big no-no for nose-blowing is using a handkerchief. always use a tissue!

• Don’t touch people. Forget back-slapping and prodding. Even common gestures in the west (e.g. handshakes and hugs) can come as an un- welcome surprise to the Japanese. Some people will actually recoil as if they’ve been touched by something unpleasant. Even if you’re in a photo with people you know well, you should keep your hands to yourself. In the end, the best thing to do is to keep a respectful distance.

• On the other hand, touching your partner in public is okay, but a show of affection shouldn’t go beyond holding hands. wrapping your arm around his/her shoulders or waist is not really done, and kissing in public is a definite no-no.

• appearing humble is a big thing in Japan. Every compliment is deflected with a “ie, ie” (no no, I’m not really that good), so you should avoid bragging about your partner, house or job. In Japan it’s more common to say that your cooking is so so, your partner is a jerk and the gift you’ve just handed over is not really that good.

• In the west, having a conversation can turn into a verbal battle, and many people literally talk over each over. In Japan, though, interrupting someone who is talking to you is considered ex- tremely rude. The Japanese usually wait until someone finishes a sentence completely before responding. It actually makes sense. I really don’t know why I have to explain this…

The common thread linking many of these “rules of the game” is that you shouldn’t do anything that may disturb other people. Granted, westerners may find some of them a little confusing or difficult to understand because in their own country they are seemingly innocuous while in Japan they can be considered offensive. when you think about it, though, a lot of the above is basic common sense. Unfortunately, too many people in other countries seem to have forgotten about it.

In general, the Japanese consider actions rude when they are a bother to anyone else. So the best thing you can do while in Japan is to observe the people around you and follow their example.

GIANNI SIMONE