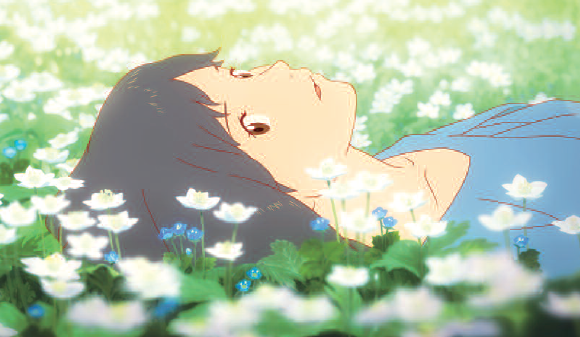

© 2012 “WOLF CHILDREN” FILM PARTNER

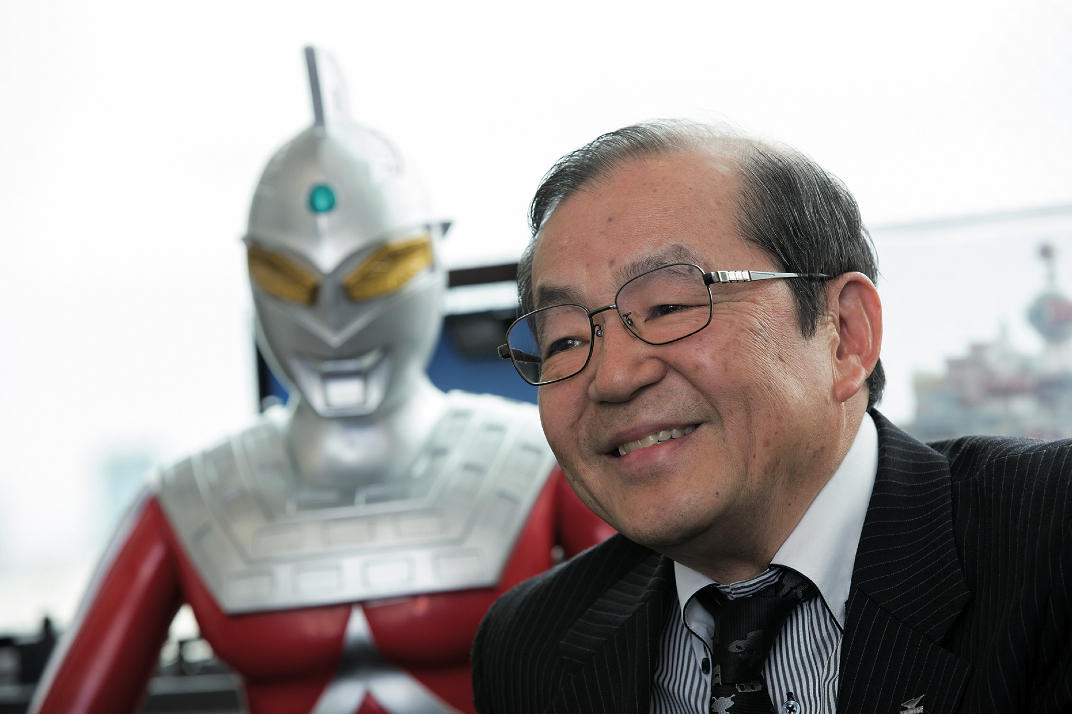

The Wolf Children, Ame and Yuki, is this Japanese film director’s latest masterpiece. It was a great success throughout Japan during summer 2012, and it is yet to be released in Britain.

How did you start working in film?

Hosoda Mamoru: When I was 12 years old, I bought an issue of the monthly magazine Animage in which there was a feature about the film The Castle of Cagliostro. It was the second movie in the series. The names Miyazaki Hayao and Ôtsuka Yasuo were quoted, and I knew nothing about them. So I went to see the movie, and I was bowled over. I was in my last year in primary school and I can remember writing in an essay at the end of the year: “I want to become a cartoon director like Miyazaki Hayao.”

Did you read a lot of manga?

H. M.: My parents didn’t buy them for me very often, but my mother loved the cinema, so she let me watch movies, and it is thanks to her I was able to see so many. So I was naturally more interested in cinema than manga.

What is your favourite film? And who is your favourite film director?

H. M.: In terms of Japanese cinema, I really like the movies of Sômai Shinji, who is dead now. In the eighties, he was very active. I like Sailor Suit, Machine Gun and Typhoon Club a lot. I started taking interest in European movies when I was at University. That’s when Fellini’s Intervista was released. When I saw the work of Leos Carax, I was completely dazzled by his talent. There are many others, but I still remember Victor Erice’s first movie, The Spirit of the Beehive, really moved me. Actually, when people ask me what my favourite movie is, that’s usually the one I quote.

Were you already thinking about directing cartoons back then?

H. M.: No. I studied painting at university and was interested in modern art. With time, I became increasingly interested in pictures and cinema.

And when you left university, you started working at Tôei Animation.

H. M.: Yes, indeed. I could have become an independent director, but I wanted experience of working in a team. That’s why I started at Tôei.

And you started making children’s films. Was there a gap between what you really wanted to do, and what you were doing?

H. M.: As you can imagine, there was a gap. Directing children’s films was completely different from what I was doing before. The fact that children didn’t know much about the way of the world bothered me. It was difficult for me to find a good way of communicating with them. So I thought of a way to try and get them interested in my work. In retrospect, I can say that it’s very interesting for a director to create for children. It allowed me to learn something very important: how to communicate with people who don’t share the same outlook on the world.

Do you think that may have something to do with your films being appreciated all over the world?

H. M.: Maybe! In general, and not just in Japan, authors draw upon their own country’s culture and references that don’t need explaining. I often ask myself what it is we can all share as human beings despite our cultural differences.

How did you start working on your films?

H. M.: I had been wanting to make a feature film for a long time. When I worked at Tôei, I was offered a job at Studio Ghibli to direct Howl’s Moving Castle. I had only directed short movies before, so I gladly accepted Ghbli’s offer. In the end, the project was developed without me, but I increasingly wanted to make a feature film. So I left Tôei Animation for Madhouse. That’s when I directed The Girl WhoLeapt Through Time.

Wasn’t it hard to leave a place you had been for such a long time, for a new adventure?

Wasn’t it hard to leave a place you had been for such a long time, for a new adventure?

H. M.: I think many people hope to make their own movie. But it’s very difficult. And if you fail the first time around, there’s no second chance. Not everybody is lucky enough to get a first chance. But if you are given one, then you need to put all you have into that movie, even if it means risking your life, your future, your family, and your pride. So it was out of the question to stay at Tôei. I needed to direct my own movie. And I was ready to sacrifice a lot to achieve that. It was

a weird feeling, but I had the impression I had reached a point of departure.

Tell us about your latest movie, The Wolf Children, Ame and Yuki. How was the project born after the success of The Girl Who Leapt Through Time and Summer Wars?

H. M.: The Girl Who Leapt Through Time was a love story. Then I made Summer Wars based on my experience of marriage. The Wolf Children, Ame and Yuki, is about how you bring up a child. Many people are concerned with this. Everybody has parents, so it’s a common theme for all human beings. In spite of this, there are very few films on the topic.

In your movies, isn’t the main character often a woman?

H. M.: Yes. Women are photogenic. I always look for someone with great vitality for the main role, someone who can overcome all sorts of difficulties.

Does this mean that women have more vitality than men?

H. M.: Yes, I think so. Men’s vitality is different. For men, it’s all about winning or losing. Whether in work or in love, men always react that way. But for women, winning or losing doesn’t really mean much. They make different choices in life. Each one of them develops her own values, her own sense of what life is about. Men are too simplistic. We rely on only one value. And we’re not photogenic. That is why I’m inspired by women’s vitality, because they have the power to change the course of a life. I feel comforted when I see what they can do.

In your opinion, did the tragic events of 11 March 2011 have an influence on the concept of family in Japan?

H. M.: I think that the way the Japanese think in terms of family has changed a lot since the earthquake. I think they have become aware of what is most important. Before, we used to say, “this is important, and that is important too.” Everything had the same value. 14 ZOOM JAPAN number 5 october 2012 Since March 11th, I think children are at the heart of our preoccupations again. We have finally understood that it is essential to raise our children, even if the world has been completely destroyed. We ask different questions: “In case of a major crisis, how should we bring them up? What do we need to do it?” Since the earthquake, we’ve come to understand that the only thing that counts is “protecting and bringing up our children”. There is a direct link between The Wolf Children, Ame and Yuki and Japan since March 11th.

During the world premiere in France, you were asked many questions about the importance given to the countryside in your movie. Had you always planned that the story should take place in Toyama, the region where you grew up?

H. M.: Because the film is about the relationship between children and their parents, I thought about my mother a lot. I am an only child. I questioned the feelings I had had for my mother while growing up. I have always wondered if, as her son, I had contributed something to her life. Because she is dead, I wasn’t able to ask her, but that’s what I was thinking about while making this movie. And that’s also why I naturally imagined the story happening in the region in which I had grown up.

So it had nothing to do with describing the contrast between a big city and a village?

H. M.: No. But you’re right, I’m often asked if the idea in the movie was to draw a contrast between nature and the city. In fact, for personal reasons, I wanted to show children growing up in the countryside. Not everybody is lucky enough to grow up in the countryside, so I thought it would be a good idea to show it and demonstrate other ways of building one’s life.

Is the countryside a model?

H. M.: Yes. The countryside isn’t just a place where nature is generous and good for humanity. The area in which I was born is quite wild. It’s a village situated at the foot of the Japanese Northern Alps. Life there can be quite difficult when compared to big cities like Paris or Tôkyô, where you have access to everything and it’s easy to bring up children. That’s why I thought it a good idea to show how children are raised and grow up in the countryside.

In the UK, too, there is growing enthusiasm for ecology. But most of the time we have an ideal vision that has nothing to do with reality. We tend to see things through rose tinted glasses.

H. M.: I completely agree. Nature isn’t easy. That is why the movie has nothing to do with ecology. You only have to look to the events of March 11th 2011. That day, nature destroyed many lives. She isn’t always gentle with us, but despite the conditions, humanity survived. We’ve been trying to protect nature from civilisation’s progress for 30 to 40 years now. But when considered on the scale of “human history”, nature has always been stronger. She can be dangerous, just like she was on March 11th. It is essential to think of children’s wellbeing whatever the environment in which you find yourself.

When watching the movie, I couldn’t help but wonder if you wanted to show the wild side of man, with these half-wolf, half-human creatures?

H. M.: I chose to create half-wolf and half-human creatures because I feel they’re representative of how children are. They have two faces, one is closer to nature and the other is closer to civilisation. When growing up, they lose their naturalness little by little. They become aware of society and become human. It’s called becoming an adult, but I’m not convinced by the process. Some people succeed in keeping their wild side, in staying natural.

At the start, it is Yuki who is closest to the universe of wolves, but then she turns towards the world of human beings. Is there a meaning to this evolution?

H. M.: Her little brother, Ame, is quite a weak child in the beginning, but he chooses to turn towards the world of wolves when growing up. Children grow up in different ways. They don’t always choose the same path. They can completely change and that’s part of their dynamic growth. Yuki is very curious and lively. When she walks into the world of humans, she fits in easily. On the other hand, Ame is cautious. He increasingly resembles his father, and he ends up dressing and thinking the way his father does. The moment when Yuki and Ame see their destinies transformed in the movie is very important.

Is it a coincidence that the date on the father driver’s licence is March 11th?

H. M.: It’s a coincidence. His birthday is February 11th. In Japan, a licence is valid until a month after the driver’s birth date. That is why March 11th on the licence appears several times during the film. Although it is a complete coincidence, it’s hard not to connect it to the current situation in Japan. When he dies in the movie, the only thing that remains is his driver’s licence. Many people may have experienced the same situation. That Hana, the main character, ends up alone with her two children, and respects her dead husband’s will is very symbolic.

Could you tell me about the team you work with?

H. M.: Sadamoto Yoshiyuki is the character designer I have been working with since The Girl Who Leapt Through Time. I couldn’t have imagined making this movie without him. Yakagi Masakatsu wrote the music. It’s the first time we have worked together. It’s also his first experience composing music for a movie, but what he wrote is very subtle and moving. He has

a rare talent.

What project do you have planned now?

H. M.: I can’t think of future plans before a movie is finished. By listening to the viewers’ comments, I try and understand what they felt, what we need to do now, and that’s what is important. It gives me something to chew over and then I can start writing a new story.

Lately, some magazines have been saying that you are the new Miyazaki.

H. M.: I am not Miyazaki Hayao. He is what led me into film, but when I write a story, I do not do it to resemble him. What is interesting in cinema is the director’s capacity to create a multiplicity of views for the audience. I can’t say Miyazaki Hayao didn’t influence me, but I would like to write my own films.

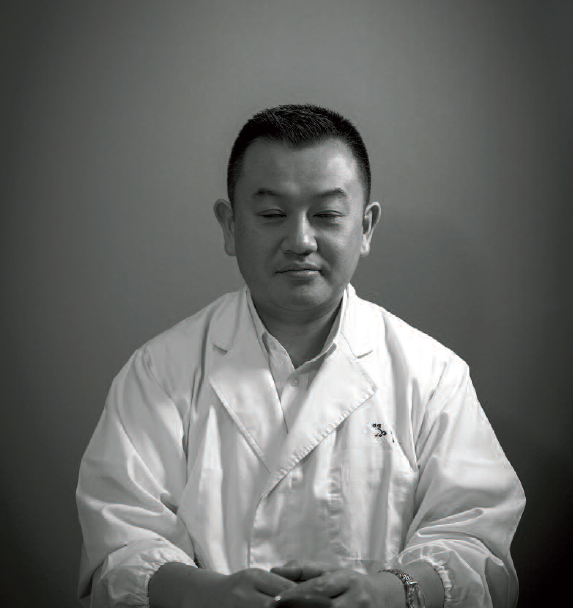

Interview by Yatabe Kazuhiko and Odaira Namihei

Photo: Bruno Quinquet