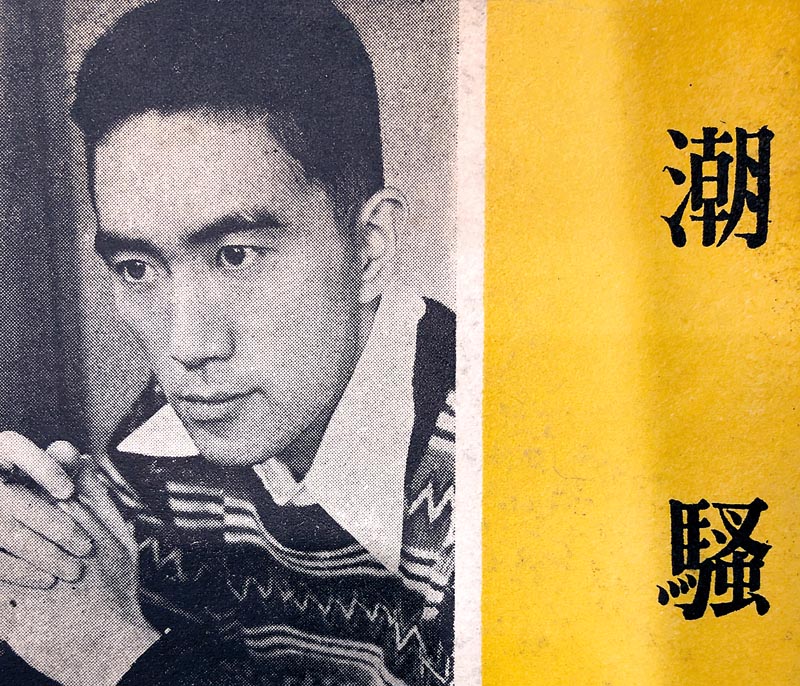

On 25 November 1970, the writer killed himself in a spectacular manner. We look back at the last years of his life.

Mishima Yukio’s life can be roughly divided into two periods, both of them characterised by violence, death and political upheaval. In this article, we will focus on the latter half of Mishima’s life – particularly the last ten years of his life – and his relationship with right-wingers.

While violent struggles in the 1960s are usually associated with left-wing student demonstrations and striking workers, Japan was teeming with ultra-nationalist groups as well. A police report in 1956 identified 95 right-wing groups, with a total membership of 67,000. The 1960 Anpo Struggle became a catalyst for the formation of more groups, so much so that by 1962 they had swelled to 400, with a membership of 100,000.

Biographers and commentators agree that 1960 was a crucial year in Mishima’s life as it marked a major turning point in his career. Mishima was obsessed with the Anpo protests. Though he never joined the fray, he followed news coverage of the daily clashes between protesters, the police and yakuza-reinforced right-wing groups, going so far as keeping relevant newspaper clippings.

By 1960, Mishima was a famous writer and a media darling who had already been nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature. However, he did not write anything specifically political until June 1960, when one of the leading national daily newspapers, the Mainichi Shinbun, published an opinion piece entitled “A Political Opinion” in which Mishima praised the Anpo protests from a nationalist point of view as an example of how the Japanese were rejecting American control of the country.

This piece inaugurated a new phase in Mishima’s life when he presented his conservative stance on politics and the current state of Japanese society, and reached an initial peak with the publication, in December 1960, of “Patriotism”. According to Nick Kapur, the author of Japan at the Crossroads, a book about the Anpo Struggle and its aftermath, the events of 1960 “awakened in Mishima an understanding of the power of the spectacle, and this understanding would be a guiding force in his future writing and public behaviour in the ensuing decade leading up to his spectacular death”.

The Japanese right must have come to the same conclusion as they suddenly stopped theorizing and sprang into action with a series of ferocious attacks on left-wing activists and politicians. On 17 June 1960, for instance, Social Party leader Kawakami Jotaro was injured in a knife attack, and on 12 October, Socialist Party chairman Asanuma Inejiro was stabbed to death during an election debate on national television by Yamaguchi Otoya, a 17-year-old youth. It is worth noting that after his arrest, Yamaguchi hanged himself after writing Shichisei hokoku (Would that I had seven lives to give to my country) on a wall, the famous last words of a medieval samurai and the same motto that was written on Mishima’s headband when he committed suicide.

“Around this time,” says Mishima biographer Damian Flanagan, “Mishima’s ideas caused him to fall out with his long-standing theatrical collaborators, the Bungaku-za, over his play Yorokobi no koto (The Harp of Happiness, 1964), concerning a terrorist plot and police infiltration by a communist radical. Many members of the troupe were left-leaning sympathisers of Maoist China and refused to put the play on without some alterations. Mishima, disgusted at the suppression of freedom of speech, broke away from the group entirely.”

More surprisingly, according to Flanagan, Mishima also had a rather problematic relationship with ultra-nationalist groups. “In his 1960 novel, After the Banquet, he wrote an unflattering portrait of a real-life right-leaning politician,” Flanagan says, “and became the target of a long-running and mentally exhausting invasion of privacy case that took years to resolve. Meanwhile, Mishima fell out with the other artists of his literary coterie, The Potted Tree Group, when Yoshida Ken’ichi – the novelist son of former prime minister Yoshida Shigeru, failed to back him over the After the Banquet controversy.”

In the spring of 1961, Mishima became the target of right-wing death threats. It all began in the fall of 1960, when Chuo Koron magazine published Fukazawa Shichiro’s “Furyu mutan” (An Elegant Dream), a short story about a leftist revolution that ends with the Imperial family being beheaded. The reaction from the ultra-nationalist groups was such that not only Fukazawa but many other left-leaning writers and critics who had taken his side went into hiding. As for Mishima, he became the target of death threats after a widespread rumour that he had personally recommended “Furyu mutan” for publication. In the following days, thugs began to scout out his house for possible attacks, and he is said to have patrolled his garden every night for weeks, armed with a samurai sword.

“For many lesser people,” Flanagan says, “all these setbacks and strains with those both on the right and left of politics, would have been crushing, but Mishima powered on persistently, ingeniously experimenting with new literary forms. In fact, what strikes me most about the last period of Mishima’s life is his relentless work ethic. He was pouring out not only that vast masterpiece of high literature, The Sea of Fertility tetralogy, but also a large number of fascinating plays – in Western and Kabuki styles – together with psychedelic, hipster novels like Life for Sale, as well as a seemingly endless stream of cultural and historical commentary, literary critique and novels for the female market. Mishima’s productivity was quite astonishing, right up until his final day.”

Mishima once said, “I’m confident that my actions are harder to understand than my novels.” Therefore, some think of his literature as being separate from his political thoughts and actions. Flanagan considers that all Mishima’s literary works stand independently, informed by a dense mix of influences from Greek tragedies and Heian romances to Raymond Radiguet and George Bataille, meaning that one could discuss them in connection with literature and ideas from around the world. “However, it’s also true that Mishima was such an outstandingly fascinating individual, and his life was so transformative and dramatic, that inevitably each one of his literary works is a sort of jigsaw piece,” Flanagan says. “Of course, there was no ‘one’ Mishima. He was always evolving as a thinker and a person, seemingly uninterested in politics as he stood aloof and watched the anti-Security Treaty riots of 1960, before appearing to lay down his life for his new-found political beliefs in 1970. He was an enormously complex man and he manifested that personality in so many different ways that there is ultimately no getting to the bottom of his books or his life.”

According to Flanagan, there is always a nexus in Mishima’s works between politics, aesthetics and existential questions. “In the earlier works, of the 1950s, political ideas are more latent, hinted at rather than overtly expressed,” he says. “Ideas about beauty and identity take centre stage. In The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, for example, you can see the Golden Pavilion as a transcendent, indestructible vision of beauty, but you can also read it politically as a symbol of the emperor himself, as something elemental, sacred and indestructible in Japanese culture. When the characters of Kyoto’s House all undergo existential crises, they reach out for different ways to confirm their sense of self – sadomasochistic fantasies, art or right-wing politics.

“Mishima himself, at this point, was far more interested in aesthetics than politics. In fact, it would be more accurate to say he was more interested in the aesthetic potential of politics. In his 1961 short story “Patriotism”, the backdrop is the failed rising of young army officers in February 1936; they want to clear the clouds – corrupt politicians and industrialists – blocking the imperial sunlight. Yet the political background is not what interests Mishima: it is merely a vehicle to stage a scene of stylised sex and suicide.

“Mishima wanted to achieve that dramatic, beautiful end for himself and he increasingly came to see that he needed politics to give his end some potency and meaning. His final day was more a carefully staged coup-de-theatre than a coup d’état. That’s not to say, of course, that the politics of his final years, when he suddenly turned himself into a right-leaning activist, were without meaning. Once Mishima realised that he needed politics to die in the magnificent, beautiful manner he craved, he threw himself wholeheartedly into examining political questions, both contemporary and relating to the early Showa period in which he was brought up.”

The late 1960s were the age of the Vietnam War, the Cultural Revolution in China and student riots across the world. There was a palpable sense of social and political unrest, a real feeling that long-standing institutions were crumbling and a new world – good or bad – was coming into being. “Mishima places himself in the middle of that maelstrom,” Flanagan says, “dreaming of being cut down by communist insurgents as part of a Praetorian Guard defending the Emperor, while imagining in a novel like Runaway Horses what it must have felt to be a right-leaning radical of the 1930s. He began to consciously emulate the insurrectionary officers of the February 1936 rebellion. He dreamt of dying in the anti-Vietnam War riots of October 1969 and felt disappointment when they were easily suppressed by the police, leaving him to find some other stage in which to engineer his own death. And yet while all this was going on, he was also able to coolly detach himself from political tumult and write non-political works.”

Mishima’s patriotism took a new turn when he gathered between 80 and 100 right-wing students and formed his own private army. At first, it was called the National Defence Army but he later changed its name to Tate no Kai, the Shield Society. Its avowed purpose was to oppose communism, maintain the national spirit and defend the emperor. “I particularly picked up the students from the university where the conflict or the trauma happened,” he said in an interview he gave in rather good English. “Such a minority of students who cannot be involved in the leftist movement felt very isolated and then separated. So in some sense, they believed in their own Japan and Japanese spirit, but it was completely denied by the leftist student movement.”

“In the press, Tate no Kai was often lampooned as toy soldiers dressed in bell boy uniforms,” Flanagan says. “Mishima actually spent a small fortune on the uniforms, which he had specially designed by Igarashi Tsukumo who had designed uniforms for General de Gaulle.”

The Tate no Kai even had its own hymn:

The young samurai warriors have risen, reborn

The light of daybreak gleams on our cheeks

Red as the Rising Sun on our flag of great truth

March gallantly Tate no Kai

Mishima’s army may have been derided by the media and public opinion, but much of the political and military establishment had much warmer feelings towards it. “Many prominent LDP politicians and cabinet members had meetings with Mishima and the Tate no Kai, and he was discreetly encouraged by high-ranking officials to run for political office,” Flanagan says.

Among the people whom Mishima met with was Nakasone Yasuhiro who was to become defence minister in 1970 and prime minister in 1982. He also went to Sato Eisaku who was then prime minister. He got both men’s support. From Nakasone he got introductions to the senior officer of the armed forces, and from Sato, incredibly enough, he got money that originally came from right-wing businessmen. Eventually, Mishima and Nakasone fell out with each other because Mishima wanted to see a nuclear Japan while Nakasone did not want to go that far.

Meanwhile, the Japanese military welcomed the Tate no Kai with open arms, allowing them to regularly train alongside the regular Japanese army. “Indeed, on the day of his death, a small five-men Tate no Kai delegation was able to take a general hostage at the SDF Headquarters because Mishima had arranged to meet the general in his office to introduce some promising Tate no Kai recruits to him,” Flanagan says.

“No street demonstrations for us,” Mishima said about his army, “no placards, no Molotov cocktails, no lectures, no stone-throwing. Until the last desperate moment, we shall refuse to commit ourselves to action for we are the world’s least armed, most spiritual army. Some people mockingly refer to us as toy soldiers. Let us see.”

Eventually, on the day of his death, Mishima was mocked mercilessly by the members of the Self-Defence Forces who had gathered to listen to his speech, and for many years the rest of the country tried to forget about him. However, according to Flanagan, he remains one of the giants of modern Japanese literature and still enjoys a strong connection with today’s youth. “In the 150 years since Japan entered the modern world with the Meiji Restoration in 1868, there have been two writers of outstanding natural ability who stand head and shoulders above the rest: Natsume Soseki and Mishima Yukio,” he says. “If you were going to read just two writers of the last century and a half in Japan, Soseki and Mishima would be the ones. Superficially different, at heart their subject is the same: Japan’s traumatic engagement with modernity.

“Just about every other writer in Japan during this long era of modernity has played off one of these two in some form or other. For example, I have written elsewhere about how even a writer like Murakami Haruki – who claims to have ‘scarcely read Mishima at all’ – was in fact profoundly influenced by Mishima. Not because he copied his style, but because he went the other way. Mishima’s magnificently stylized and beautiful Japanese meant that Murakami had to write in heavily American-influenced prose, stripped of Japanese cultural references, to try and escape his influence. Everywhere you look in Murakami’s early novels, you sense Mishima’s looming presence: he’s the big elephant in the room.

“From our perspective in the 21st century, it’s really Soseki and Mishima who truly matter, and it’s those two writers I would encourage younger generations not just in Japan but all around the world to continue to read and explore.”

MARIO BATTAGLIA