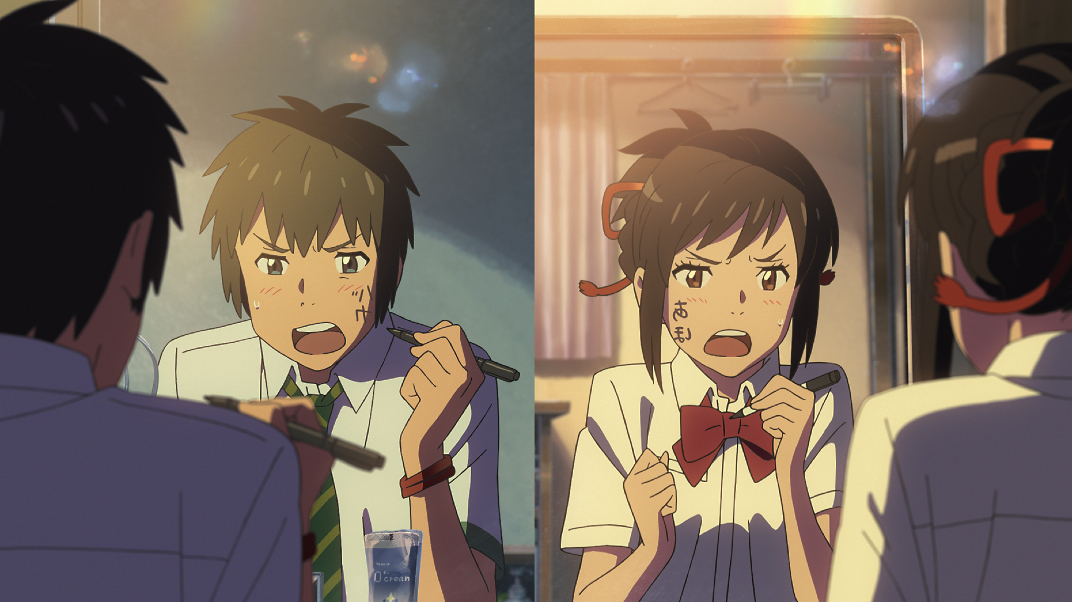

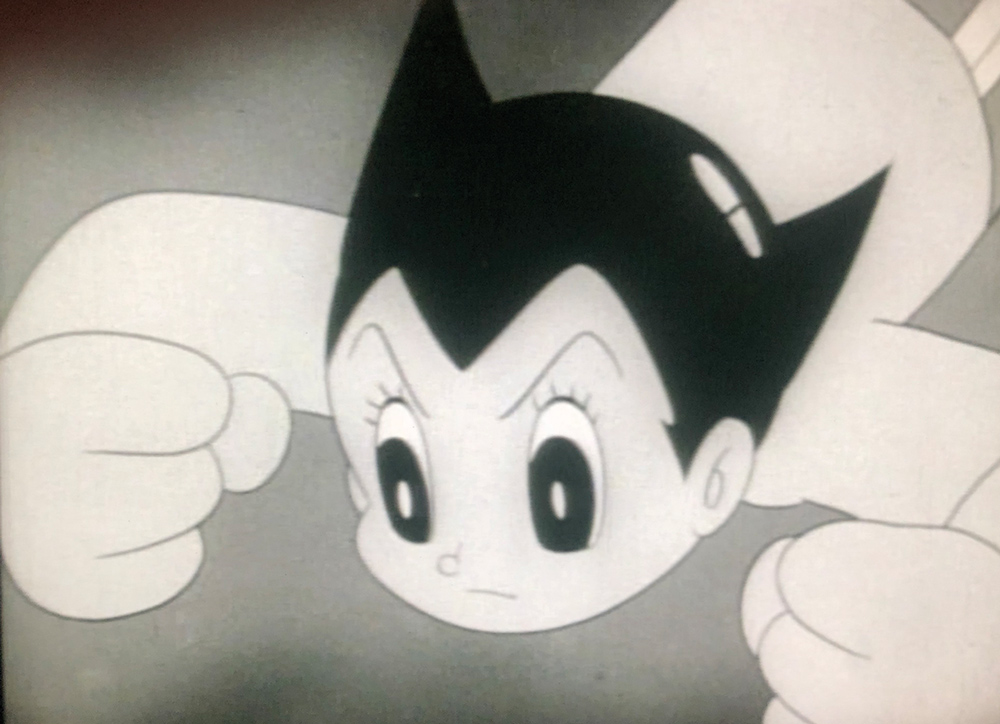

The famous 34th episode of Tetsuwan Atom was produced by Studio Zero in 1963.

To explain the reason behind our great love of Japanese anime, we need to look at the role played by the small screen.

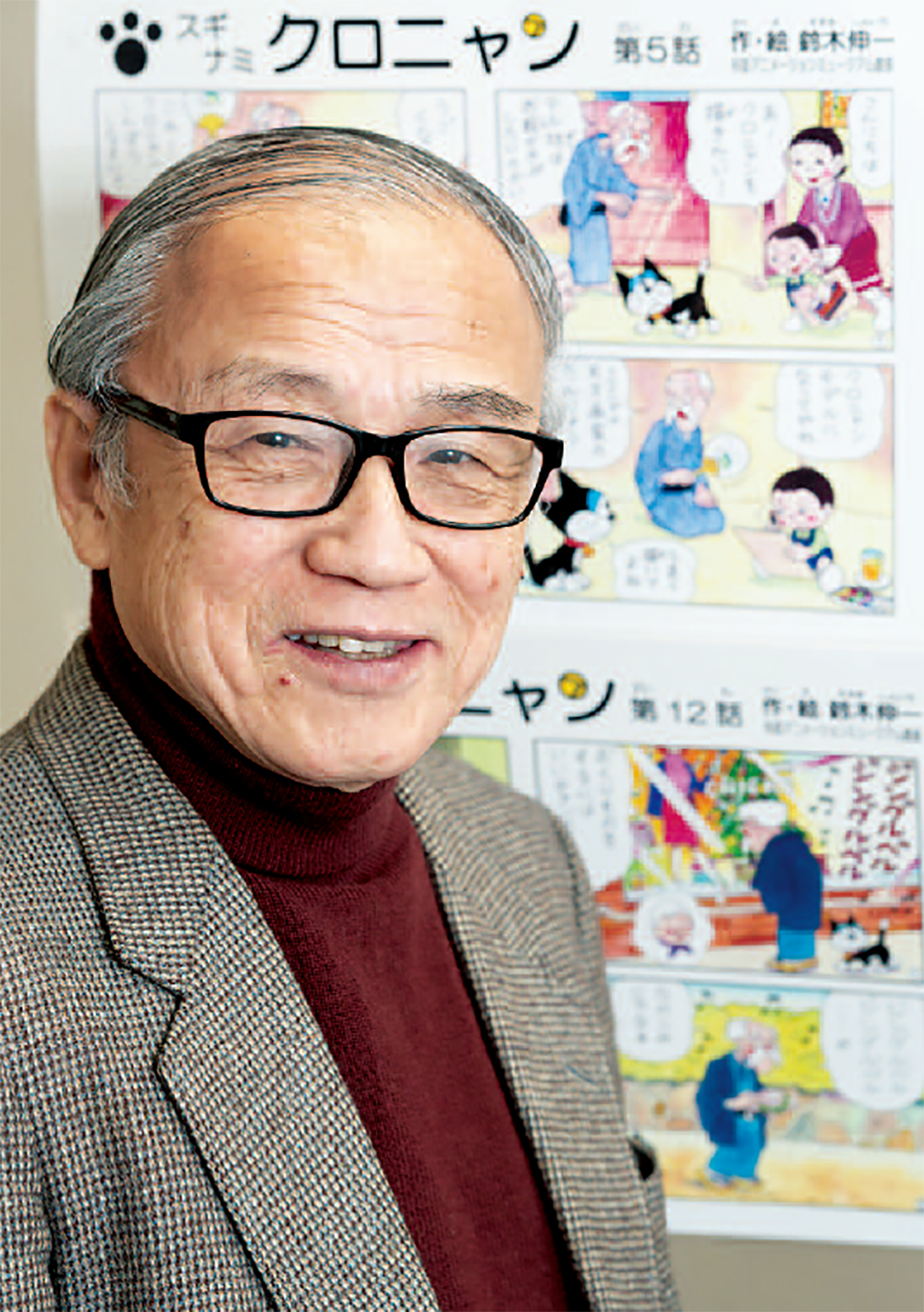

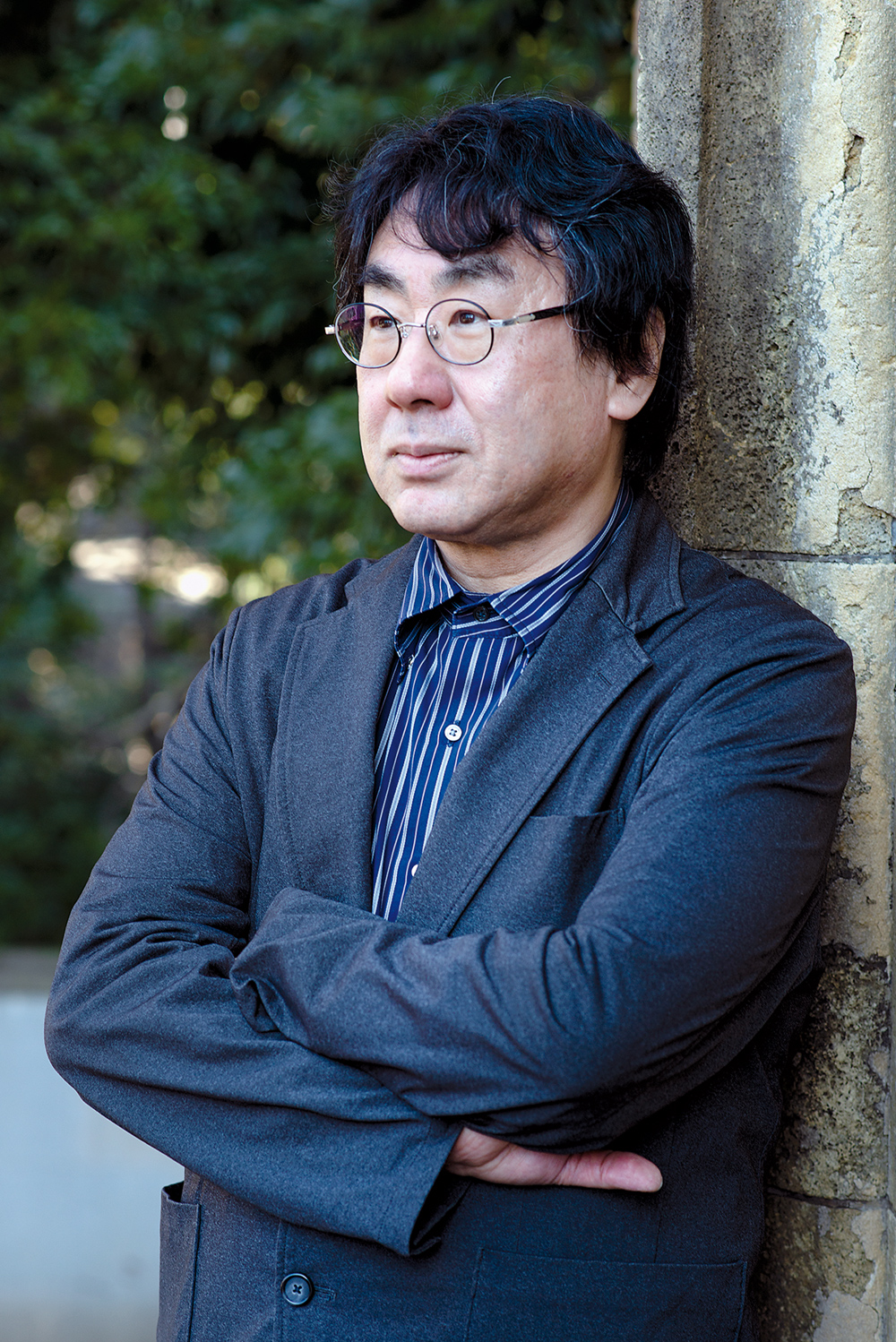

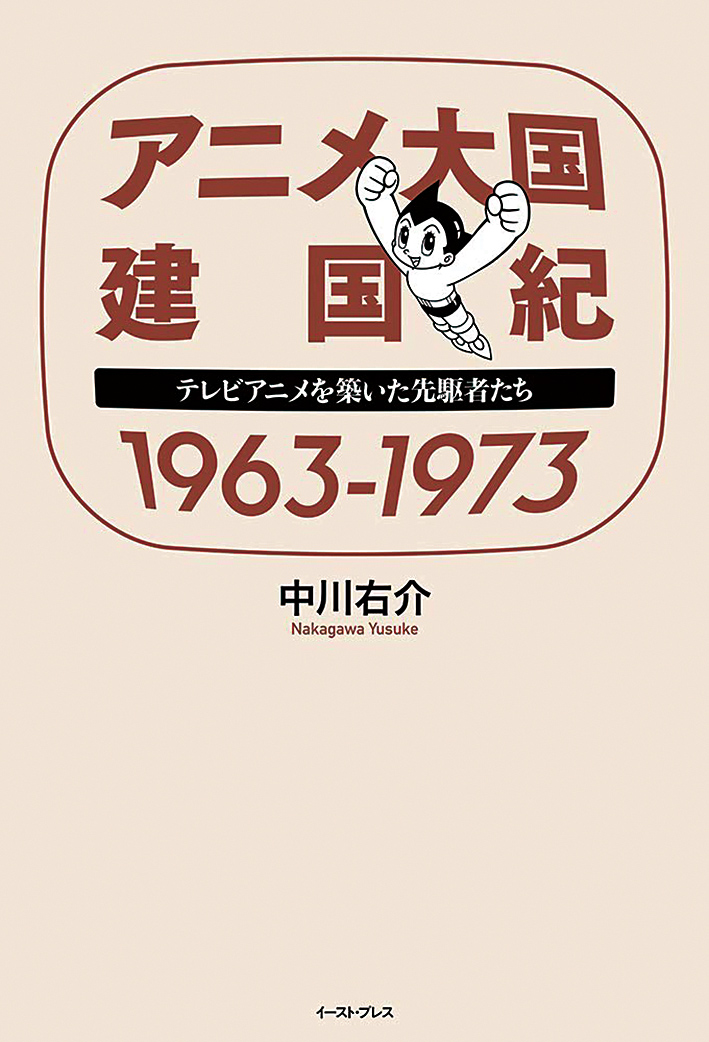

Writer and editor NAkAGAWA Yusuke is the author of more than 70 books about Japanese pop culture. he was kind enough to talk to Zoom Japan about his latest effort, a mammoth history of animation entitled Anime Taikoku Kenkokuki 1963-1973. Terebi Anime o Kizuita Senkushatachi (The Birth of the Anime Powerhouse (1963-1973): The Pioneers Who Built TV Animation).

1963 is the year TV anime was born in Japan, but why did you end your story in 1973?

NAkAgAwA Yusuke: first of all, my story starts with the making of Tetsuwan Atom (Astro Boy), so I thought that it should end when Mushi Production, i.e. the studio that made Atom in 1963, went bankrupt in 1973. That decade represents the pioneer period of anime making in Japan, and Mushi Pro was at the heart of it. One year later, MATSUMOTO Leiji would create Space Battleship Yamato, inaugurating a new phase in the history of animation. Also, in practical terms, though my book only covers the first postwar decade in anime history, it’s almost 500 pages long. It would have been physically impossible to add hundreds more pages (laughs). It took me almost 500 pages to cover the first postwar decade.

As you just mentioned, TEZUKA Osamu’s Atom is the very first made-in-Japan TV anime series. Significantly, its debut was on Fuji TV (one of the country’s major commercial broadcasters) on New Year’s Day.

N. Y.: Yes, it aired on a Tuesday at 18:15. In Japan, the 18:00-19:00 time slot comes just before prime time (or Golden Time, as it’s called here), and until recently it was often devoted to anime and tokusatsu (live action special effects) shows (e.g. Kamen Rider, Ultraman) because school children watched TV at that time. The same episode was later rebroadcast at 16:00 or 17:00 just in time for when the kids came home from school.

By the way, you were born in 1960, three years before the debut of Atom on the small screen. what are your first anime-related memories?

N. Y. : Obviously, my memories are not so clear, but I remember watching Atom when I was three years old. Not only was it the first anime I saw but it is also the first TV show I remember watching.

I used to collect the stickers they gave as a free gift with Meiji chocolate (Meiji was the show’s sponsor). I can still sing the Atom song! In other words, for as long as I can remember, I’ve been a big Atom fan, even though I actually have better memories of Little Ghost Q-Taro (1965-67). for example, I remember putting a piece of white cloth on my head and playing at being Q-Taro.

Atom was a revolutionary TV show in those years. It was also the model for the anime series that came later.

N. Y.: That’s true. Tezuka knew that his studio only had limited resources, but he believed that as long as the story was engaging, one could make TV anime cheaply and still make it successful. for instance, he introduced labour-saving techniques like using fewer frames per second and even a lot of still pictures.

According to TOMINO Yoshiyuki, who worked as a screenwriter and made the storyboards (he later created the Gundam anime franchise), the production environment wasn’t so stable. halfway through the show, for example, the main animators were moved to work on Kimba the White Lion, so every time production ran late and a new episode wasn’t ready for the weekly broadcast, they had to use bits from previous episodes or scenes from their anime library.

In an earlier interview with anime director SUZUKI Shin’ichi, I heard that even Studio Zero was briefly involved in making Atom.

N. Y.: Studio zero was started in the same year Atom first appeared on TV. It was made up of manga artists who lived in Tokiwaso, the apartment building in Tokyo where Tezuka himself had lived in the mid-1950s. I’m talking about ISHINOMORI Shotaro, FUJIKO fujio, AKATSUKA fujio, and SuzukI himself. In a sense, they were all Tezuka’s disciples. In the summer of 1963, Tezuka put them in charge of drawing the show’s 34th episode. however, each artist drew the characters in a slightly different way. There was no visual unity. Tezuka didn’t like the result, and Studio zero was never commissioned again. This episode, by the way, went missing for a long time. When it was rediscovered, it was restored and added to a DVD box release in 2002.

Atom’s original run lasted four years. That’s a quite long time for a TV anime.

N. Y.: It could have gone on even longer. In the end, Meiji Confectionary, the sponsor, decided that it had run its course. however, the show was still incredibly popular. When fuji TV made the announcement, it was flooded with letters of protest, and the final episode, which aired on 31 December 1966, had a 20% higher rating.

Let’s take a step back and return to 1963. In that same year, Atom was followed by more anime series, namely Tetsujin 28-go (Gigantor), Eightman and Wolf Boy Ken. The first two were produced by Eiken (at the time, the studio was still called TCJ) while Wolf Boy Ken was made by major studio Toei. I guess each studio had a different approach to anime making?

N. Y.: The main difference between Atom and the series that followed it was that Atom was Tezuka’s dream project; he really wanted to turn his manga into an animation. The other projects, on the other hand, were created for financial reasons; the broadcasters and the sponsors saw that anime was a new way to make money, so they approached the studios to produce them. Tetsujin 28-go, for example, was sponsored by food company Glico. The author of the original manga, YOkOYAMAMitsuteru, had never thought about turning his story into an anime.

Eightman (Japan’s earliest cyborg superhero) is an interesting early example of synergy between sponsors and creators. Eightman uses nuclear power as an energy source, and in order to prevent overheating of his ultra-small nuclear reactor and electronic brain, he must “smoke” a cigarette- like coolant. That’s because the sponsor, Marumiya food Industry, hoped to sell its cigarette- shaped chocolate to all the kids who watched the show. And so they did, as this anime proved very popular and reached an audience rating of 25.3% in September 1964.

As for Wolf Boy Ken, this was Toei’s first TV anime production. This company was much bigger and had more technical know-how than Mushi Pro and TCJ (Toei employed around 3,000 while Mushi Pro never had more than 500, and TCJ was probably even smaller). They only focused on animated feature films and in the beginning were rather skeptical about TV anime’s potential. Their reasoning was that animation was equivalent to fluid movement, and Mushi Pro’s work was too spartan, too poorly made, to have enough visual appeal. But when they saw how popular Atom had become, they created their own TV animation studio and TSUKIOKA Sadao – Tezuka’s former assistant – was put in charge of Wolf Boy Ken.

At the time, anime greats TAkAHATA Isao and MIYAZAKI Hayao were employed at Toei. It seems that the latter, in particular, was quite critical of Tezuka’s working method. why is that?¥

N. Y.: Well, MIYAZAKI is pretty vocal in his tastes and has criticised many people over the years, including Disney. But to answer your question, when MIYAZAKI first joined Toei, he was too young to impose his ideas and make the kind of animation he wanted. Then, Tezuka came along with Atom, and Toei began to invest more time and energy into producing TV series, which were not what MIYAZAKI wanted to make. So MIYAZAKI blamed Tezuka for crushing his dream of making animated feature films. eventually, as you know, he had to leave Toei and start his own company in order to fulfil his dreams. Of course, Tezuka can’t really be blamed. After all, it was the Toei management that decided to pursue a more lucrative means of production.

Why do you think TV anime became so popular in Japan compared to other countries, and why did this happened in the early 1960s?

N. Y.: In the 1950s, Japan developed a robust manga industry that laid the groundwork for anime’s success. Tezuka was the main manga author at the time, and it was Tezuka, again, who decided to turn his manga stories into anime shows. In fact, in the 1960s and 1970s, all TV anime series were adaptations of comic stories. As for the timing of the birth of TV anime, in 1959 the crown prince (future emperor Akihito) married a commoner and many people bought a TV set to watch what the media had dubbed a “fairy tale” wedding. By 1964, when Tokyo hosted the Olympic Games, most households owned a TV. Though, nowadays, manga and anime still work closely together, it’s worth noting that to start with, manga publishers were suspicious of anime. for example, when TBS decided to make a TV show based on Eightman, they approached Shonen Magazine to acquire the story rights. however, at first, the editorial department declined the offer because they were afraid of property theft and didn’t understand anime’s potential.

A popular belief that keeps circulating in the anime industry is that TEZUKA – who wanted to make Atom by any means necessary – undersold that series to Fuji TV, and created a precedent for Japanese animation’s chronic lack of money. Is that true?

N. Y.: I’d say it’s only half true. To be sure, Mushi Pro didn’t earn much from Atom. At the time, a children’s TV programme could be made for about 500,000 yen, while a TV anime cost much more – some three million yen. That’s why nobody produced an animated show until 1963. But Tezuka said he could make Atom for 550,000 yen, which set the bar too low (or too high, if you prefer) for the competition. Now, if Mushi Pro had earned only that amount of money for its efforts, it would have gone bankrupt in no time. however, the sum fuji TV paid was only the fee for the broadcasting rights. In other words, Mushi Pro still owned the character and anime copyright, so they kept earning money from the sale of toys, merchandise, character-related goods and other royalties. It’s a fact that Mushi Pro’s employees earned much more than those who worked at the more powerful Toei. It’s said that a lot of Mushi Pro animators owned a car at a time when car ownership was still a luxury in Japan.

The problems came later, when the anime industry went through a period of restructuring, the “media mix” production system became widespread, and the studios weren’t able to hold on to the copyright anymore. That’s why many small and mid-sized companies began to struggle. At that point, however, the studio management, instead of accepting their own responsibilities, found it easier to blame Tezuka for the animators’ low wages. But when you think about it, 30 years have passed since Tezuka’s death. I think the time has come to blame someone else for the current status of animation in Japan.

One thing I noticed about this pioneer period is the level of collaboration among the studios. For instance, when Tatsunoko Production made Space Ace in 1965, scriptwriter TOrIuMI Jinzo from Mushi Pro joined, and NAKAMURAMitsuki from Toei was also part of the creative team.

N. Y.: You must understand there were still relatively few anime studios in Japan and, aside from Toei, they were quite small, so they often needed a helping hand from other companies. Nowadays, studios are less likely to lend their own people to the competitors, but on the other hand, animators tend to change companies pretty often, always in search of better creative environments and higher salaries.

Let’s fast forward to the early 1970s. In 1971, the Lupin IIImanga, which had been serialised originally between 1967 and 1969, got its first anime adaptation. Lupin III is often considered the dawning of a new era in anime history. Do you agree?

N. Y.: until the late 1960s, both production companies and TV stations had treated anime as kids’ entertainment. however, a few artists began to toy with the idea of creating stories for older viewers. At the same time, an increasing number of up-and-coming artists had the same idea and started drawing stories for junior high and high school students. The protagonists in these manga were not children but adolescents or even adults. even the stories were very different. In the past, justice was always supposed to triumph over evil, but the new stories featured bad guys as their protagonists such as a thief in Lupin III, for example, while in 1968, SAITOTakao began drawing Golgo 13whose main character is a professional assassin. These stories clearly have more adult themes, feature real weapons and cars, and have more erotic scenes.

Though Lupin III has a somewhat more cartoony look than Golgo, this anime targets an older audience of young boys who enjoy and are curious about guns, cars and women. At first, the broadcaster made the mistake of airing this anime at 19:30, at prime time, when the whole family was watching TV while having dinner. That caused a lot of embarrassment, and the show’s rating was rather low. But when the episodes where rebroadcast at a later time, all the young boys could freely enjoy the show and ratings soared.

How did anime production change in the 1970s?

N. Y.: I earlier mentioned Mushi Production’s bankruptcy in 1973, but the 1970s were years of struggle for the whole animation industry. Toei Animation, in particular, suffered a long period of labour disputes, which still continues to some extent. While Toei as a company was doing well, its animation studio was among the departments that were in the red due to high production costs. The management tried to reduce the number of employees through restructuring and early retirement, but met with fiery resistance from the union, which led to strikes and a lockout.

New practices were introduced in the industry: for instance, a single studio could no longer manage the entire process of planning, scripting, directing, drawing, shooting, and editing. As a result, the creative process was often outsourced to smaller, specialised studios. Wages began to decline around this time as the seniority-based employment system fell apart, and a system of performance-based pay was introduced. This meant that when a TV anime series ended, the staff was disbanded.

In the 1960s, Tezuka epitomised the genius with a strong personality who was able to make things happen through his creativity, personality and work ethic. But in the new decade, TV stations and advertising agencies took the initiative in planning new projects, and the studios were required to change to a corporate style more compatible with the shrewd programming policies of the broadcasters.

The story you have told in your book ends with the advent of robot anime which, coincidentally, is the first genre that was broadcast in Europe in the second half of the 1970s. How important were giant robots in Japan?

N. Y.: As we have seen, the first hit anime in television history was Astro Boy, and was followed by more robots, cyborgs, etc. When something sells (this is true for anything, not only manga or anime), everybody tries to copy it until that genre becomes overcrowded and boring. however, robot animation was revived by Mazinger Z when it came out in 1972 and Mobile Suit Gundam, which followed in 1979.

Robot anime are made in partnership with a toy maker, and the robot design, not the story, comes first. Once the design is approved, the manufacturer starts making toys. Animators are free to create any story as long as the robot appears for at least three minutes during any 30-minute episode. After all, the toy maker, who is also the show’s sponsor, only cares about selling toys and is not overly worried about TV ratings. That’s why the animators were able to come up with original characters and challenging stories. Robot anime may have been difficult to understand for elementary school children, but they contributed to significantly improving the quality of Japanese animation.

TV anime production is based on the commercial principle that all the main partners – commercial broadcasters, advertising agencies, and makers of children’s products such as sweets and toys – want to make a profit. In this respect, it’s been proven that letting creators work freely is the best way to make money.

INTERVIEW BY J. D.