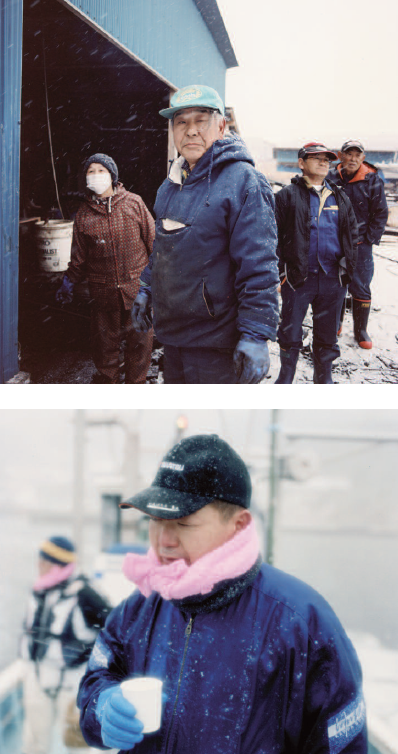

Master-brewer at the Otokoyama brewery, this former salesman carries on the tradition out of a deep love for his city.

Master-brewer at the Otokoyama brewery, this former salesman carries on the tradition out of a deep love for his city.

Otokoyama’s high quality sake brewed in Kesennuma, in Miyagi Prefecture, has received many top awards in prestigious competitions. Synonymous with high quality, Otokoyama is a respected name amongst sake brewers. On March the 11th 2011, a huge part of the brewery’s installations were destroyed, with tsunami wave stopping just a few meters from the main entrance. Despite the catastrophe, the company restarted its production two days later and the Japanese public greatly admired their decision. “Over the course of the last two weeks, I have seen many things I’d rather not have seen. Despite the terrible situation, we will be receiving new machines to make our sake, along with messages of support from across at the whole of Japan. It gives me the strength to carry on living; it makes me grateful to be alive,” Kashiwa Daisuke wrote on his blog 15 days after the disaster. He was then number two at the brewery. Aged 70, the previous master-brewer had announced that he wanted to retire because of his age, but in order to support the reconstruction of Kesennuma he decided to continue for a year. In 2012, Otokoyama was once again awarded many prizes. After this new crop of awards, the elderly master chose Kashiwa Daisuke to succeed him. Both the company’s CEO and his colleagues asked themselves whether Kashiwa really had what it takes. Admittedly, he didn’t have a great deal of experience; he had previously worked mainly as a salesman for another brewer in Sendai. In response to these worries, Kashiwa simply continued to collect awards.

For the first time in the brewery’s history, its Sotenden Junmaiginjo sake was awarded first prize in the renowned Nanbu Toji Jijo Seishu competition. “I can now say that our boss’ decision to restart the production of sake only two days after the tsunami was the right decision. Of course, at first I was still in a very emotional state, and I criticized him. Several employees had lost family and friends and the city was partly destroyed,” Kashiwa remembers. Right after the disaster, he volunteered to search for the missing, digging through the rubble of his beloved city. “I found the bodies of school friends’ wives. It was unreal,” he says. “I was in a dream. But soon, I started brewing again in a sort of semi-conscious state. I plunged into the production of sake, spurred on by the desire to be of help to people suffering the loss of those close to them,” he adds. In the small world of brewing, hierarchy is very important. The master brewer (known as a “toji”) is number one, but Kashiwa preferred to place himself alongside the workers for the sake of harmony. “Unlike traditional toji who hesitate to reveal their know-how, I set myself a rule according to which I had to share everything. Sake is not the fruit of one individual, but the result of a combined harmony among those who produce it. Brewing sake can be compared to raising children. If you are too strict, it is no good. But the opposite isn’t the answer either. Everyday sake develops a little, like a child. I have to pay attention to it in order to respond rapidly to its needs,” he explains. “I am glad that an increasing number of people enjoy our sake. But I’ll be even happier when they visit our city to discover it. Our sake is the perfect match for seafood. My greatest wish is that tourists may come from all around the world to Kesennuma to taste our sake and our fish.” he concludes.

M. S.

Photo: SASAKI Ko