Since the end of the 19th century, the Japanese have known how to combine the pleasure of travelling with eating well, with the station lunch box becoming a firm tradition.

Since the end of the 19th century, the Japanese have known how to combine the pleasure of travelling with eating well, with the station lunch box becoming a firm tradition.

Some people catch a train just to travel from A to B. Every day, thousands of Japanese use the Shinkansen between Tokyo and Osaka for business, but there are also those who pick their route in order to admire the scenery. For them, what counts is what they can see out of the window and they wouldn’t miss a second of it. Last but not least, there are those who travel hundreds of kilometres to savour the food served on a train. However, apart from a few overnight trains, there is not a dining car in sight. Ekiben (literally “station lunch boxes”) are available at the stations or are sold on the train by charming waitresses, and uphold their region’s culinary traditions. Some of these ekiben have such a good reputation that travellers will take some home for their family but most of the time, people are just happy to enjoy them while taking in the beautiful scenery out of the window. “Ekiben adds to the enjoyment of the journey, and the window out of which you admire the scenery certainly adds to the enjoyment of the ekiben. When you get back to your seat with your food, you can hardly wait to rip open the box to get at what you’ve been longing for,” is how Uesugi Tsuyoshi describes the experience for a traveller who has not only come to admire the countryside, but also to eat. He is the author of many books on the subject and the moderator of online resource Ekiben no Komado [The Ekiben Counter] that lists thousands of them. In Europe, it is usually sandwiches that are eaten when travelling by train but ekiben are a key element in Japanese travelling culture.

The word itself has a whole history behind it and is made up from eki [station] and bento [traditional boxed lunches, that are known to have been used by the Japanese since the 8th century]. When the first trains were introduced to the archipelago, what to eat onboard soon became an important topic. It is impossible to discover when or where the first ekiben appeared, as there are so many competing claims to its origins (which also illustrates how important they are). Most Japanese don’t care when the first ekiben were sold in stations, but they certainly won’t escape the debate if they buy any of the numerous books on the subject. Most of the time these guides describe the pros and cons of the various dishes on offer, but the author attempts to pin the phenomenon’s origins down to one date rather than another, usually varying between 1883 and 1885. This battle relating to the date ekiben first appeared also reveals that the history of Japan’s railway is intimately related to the country’s culinary culture and to regional specialities. This is the reason some ekiben have become as famous as many of the dishes served in the archipelago’s best restaurants. It also explains why so many are keen on travelling long distances to try specific lunchboxes. Yokokawa station has the country’s oldest ekiben counter (ekibenya) still in service. It opened in 1957 and sells the famous Toge no kama meshi (Mountain pass rice pot). The press was full of praise for this ekiben when it was launched 55 years ago and sales sometimes reach 24,000 boxes a day. Served in an attractive little earthenware pot, these ekiben are made up of a bed of flavoured rice topped with stewed chicken and vegetables. At 900 yen (around £6), Toge no kama meshi offers great value and quality, which also explains why these dishes are so popular. There really is no contest between these culinary delights and the warmed-up pizza and quiches that can be found on European trains. Ekiben generally cost under 1,000 yen, although some can cost up to 2,000 yen. One of the more expensive is the Kobe wine bento (a lunchbox including Kobe wine), sold for 1,600 yen. Available at Shin-Kobe station on the Sanyo Shinkansen line, this ekiben has two things that justify its price. First it contains Kobe beef, a product the region is very proud of. Served medium rare, it literally melts in your mouth.

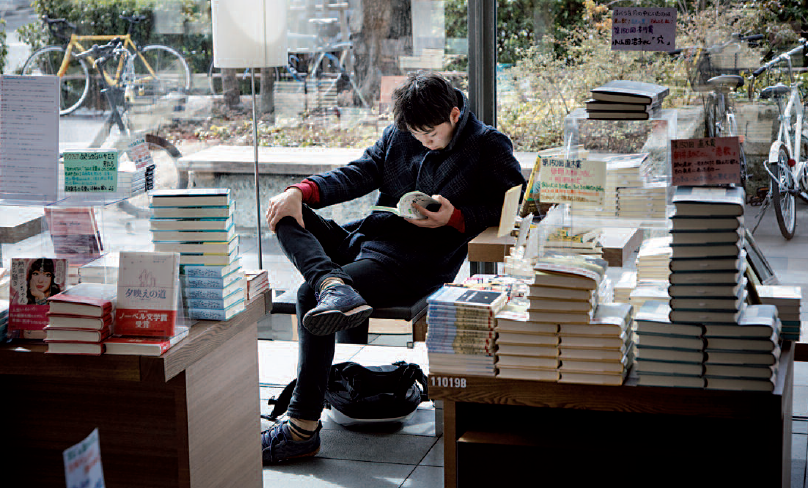

The second is that it comes with a little bottle of local wine – a treat that definitely justifies the asking price. As it is not always practical to get off the train to buy your food, the railway companies offer a service where you can order a bento onboard and it is then delivered to the train at the appropriate station. This is not available for all ekiben, but some lines have earned a reputation for offering this useful service. Ekiben are a unique and delightful moment in a journey as there are many different flavours and often unique local dishes to choose from. One particularly famous example is Oshamanbe Station on the Hakodate line in Hokkaido which offers Kanimeshi (crab meat on rice) for 1,050 yen and Mori Soba (buckwheat noodles) for 600 yen. These are only for sale at the station itself, so it’s better to order it in advance rather than stopping off to buy some, especially as the train then travels the length of the stunning Uchiura Bay. Eating crab or soba while admiring such a view takes us back to the basic philosophy of ekiben, defined by Uesugi Tsuyoshi. Ekiben belongs to Japan’s charming train culture. These delicious dishes are usually sold at kiosks on the platforms or within the station. Some vendors sell on trains, but many more can be found in the stations. One of the most famous vendors is called Yamagushi Kazutoshi. He works on the platforms of Orio Station in Kyushu and you can hear him sing “bentoooooo” at the top of his beautiful voice. Yamagushi has even recorded an album. Many travellers choose to stop in Orio to see this local star and have the chance to buy his famous Kashiwa meshi. It costs 650 yen and includes a bed of rice topped with delicious finely cut chicken that has been simmered in stock with dried seaweed and egg. On the market since 1921, this ekiben is certain to give good value among the hundreds on offer in Japan and is regularly quoted in reference books as one of the ekiben to taste before you die. The Japanese make quite a fuss over these railway bento, partly because they belong to an ancient culinary tradition, but also because they are always of good quality and fresh. Ekiben are prepared on the day they are sold in most cases and their shelf life is short, especially when they contain seafood. It goes without saying that there are no preservatives in these little restaurant-style dishes. When you watch the travellers unpack their ekiben you will see them exchange words and looks of satisfaction with their neighbours, as these bento are a pleasure both to look at and to taste. They are works of art using colours and textures, a science designed to make you want to pick up your chopsticks and start eating. Many travellers enjoy ther ekiben served with tea or a cool beer and when you are around such lucky diners you are sure to hear the little words “Umai” and “Oishii” [excellent, delicious] as they tuck in. It can make you feel quite left out if you forgot to get one of your own for the journey and have to miss out on this integral part of travelling across Japan by train.

Odaira Namihei

Photo: Jérémie Souteyrat