A few kilometres away from Sapporo, Otaru’s little port is experiencing a revival with help from a master brewer who comes from Germany.

A few kilometres away from Sapporo, Otaru’s little port is experiencing a revival with help from a master brewer who comes from Germany.

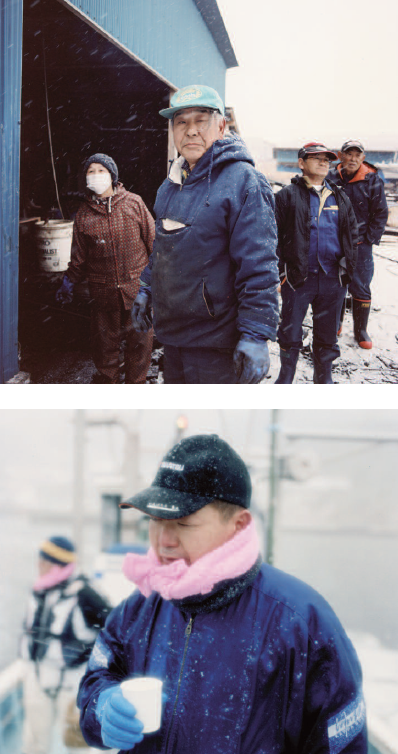

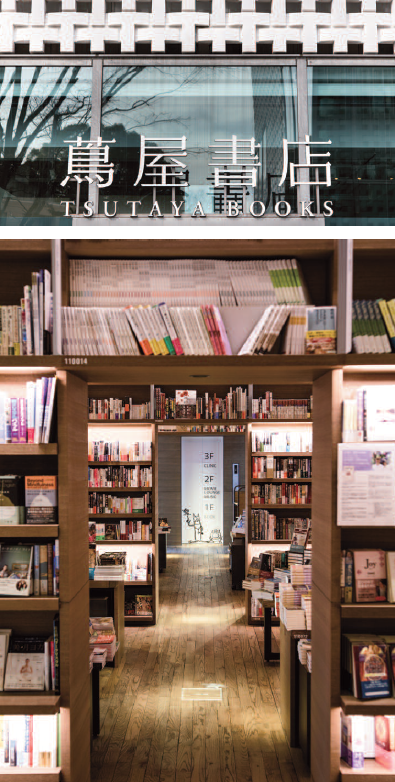

Nowadays, Otaru is a little port like any other. However, until the ninteen-forties it was the region’s economic powerhouse. It owed its importance to commerce with Sakhalin Island. After being under Japanese control from the second half of the 19th century, Sakhalin passed into Russian control again after the Second World War, and Otaru sank into oblivion. The warehouses, built over 100 years ago along a little canal, are reminders of its vibrant past, and it is in one of those buildings that Johannes Braun took up residence. He is a 44 year-old German who has been living in Japan for 20 years, and settled in Otaru after being recruited to manage a brewery. “I was working in Scotland in a whisky distillery when a head hunter offered me the opportunity to work in Japan,” he remembers. “I had quite a lot of experience in beer. My family has managed a brewery in Germany since the 17th century and I studied, and then worked in the field for quite a few years.” The relaxation in the law on the development of microbreweries triggered the start of this exciting adventure. In 1994, with a beer market dominated by Kirin, Asahi and Sapporo, the authorities decided to liberalize the sector and authorize the creation of small business enterprises in the archipelago.

This was in response to a strong demand as well as the need to revive a sector that was going through a crisis. After years of sustained growth, the consumption of beer has been in decline for the past two decades. This can be explained by the fact that over the years the sector’s biggest businesses increasingly turned their backs on the production of real beer. “They make drinks that look like beer, but that isn’t really beer. So you can’t be surprised that the consumption rates are so bad,” says the master brewer of Otaru Beer with a grin. Johannes Braun is quite obviously happy to be in Otaru. His figures are good. “They are increasing by 10% per year,” he adds. The business is going so well that he has opened a second production unit just a few kilometres away in Zenibako. “We produce 2 million litres per year, in addition to the 150,000 litres made in Otaru.” When we ask him to explain his success, he replies simply, “I make beer.” Johannes Braun had only one condition for accepting the job, and that was for him to be allowed to produce an organic and 100% natural, non-filtered beer. “The big Japanese brands filter their beer, and at the end of the day, they offer very few varieties. They are four brands that dominate the market, but they produce only two kinds of beer. I thought I might succeed in the challenge I had set myself by offering different kinds of beer,” says the brew master. The Otaru brewery offers dunkel (dark beer), pilsner (pale lager), and weiss (wheat beer), not forgetting all the seasonal beers. The only downside of this wonderful venture is the difficulty that Johannes has in exporting his beers. “Because it is 100% organic, it doesn’t travel very well and won’t survive the distribution methods currently used that require long periods in storage,” he stresses. But Johannes Braun is not too bothered by this. “If the beer can’t travel to the consumer, the consumer must travel to the beer,” he says. Soko No. 1 warehouse, where the production unit is situated, has been turned into a huge Bierkeller, worthy of it German counterparts. The decoration is German, the music is German, and most of the food is as well. “People love it,” says the master brewer. At the centre of this venue, which resembles Bavaria rather than Japan, is a copper brewing room that he imported from Germany. From producer to consumer – with no middleman. The quality of Otaru’s water and the yeast that Johannes Braun produces himself both contribute to the beer’s inimitable taste. Thousands of people travel to Otaru for its beer, which is bringing back some of this little port’s lost vitality.

O. N.

Photo: Odaira Namihei