Japanese products are well-known for their quality and beauty. We found out how it all began.

The “Zakka – Goods and Things” exhibition currently taking place in Tokyo (see related article) is a riot of steel, plastic, wooden, and paper products of all different shapes and sizes. However, there is one clear omission: industrial designer Onishi Seiji’s collection of aluminium goods. Onishi’s collection seems to be better known abroad than in Japan, and it has already travelled three times to Europe, currently being exhibited at the Maison de l’Architecture Poitou- Charentes in Poitiers. Born in 1944 and raised at a time when aluminium goods were ubiquitous, over the years Onishi has amassed hundreds of household appliances, toys, assorted tools, kettles and other cooking utensils, mainly from the first half of the last century. With their original coverings such as paint, labels or excess decoration removed, these objects were stripped bare, down to their essential form. In their simplicity, anonymity and material nakedness, they express the poetry of everyday objects clearly and with out pretension.

Zoom Japan met Onishi in Tokyo’s very trendy Daikanyama district to discuss the timeless allure of these humble objects.

When did you start collecting these objects?

O. S. :The very first time I became aware of these things I was about ten years old… I know, I’ve always been quite eccentric (laughs). Anyway, I was in elementary school. One day one of my classmates showed up with a round metal lunch box. I’d never seen anything like that – all lunch boxes were square – and I decided I wanted it for myself. At the time, aluminium was already being replaced by plastic, and today nobody wants to use an aluminium lunch box or other food container, because they say it’s cold to the touch and unhealthy. Even now that aluminium goods are becoming popular again, they are all being manufactured abroad in places like India and Vietnam, as local factories have disappeared.

Are all the pieces in your collection made in Japan?

O. S. :Yes, I limit myself to Japanese products. Aluminium products can be found everywhere in Asia, Europe or America, but Japanese goods have a particular smell. It’s like water or soil. A farmer, for example, can tell you where a certain soil comes from. For me it’s the same with aluminium. I told you I’m strange (laughs)!

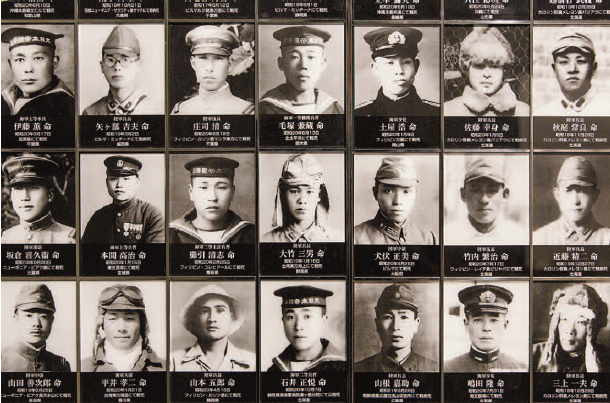

It’s interesting how you can easily spot the difference between pre-war and post-war items. Older objects from the 1920s and 30s are recognizable by their finer quality. That’s because Japan had plenty of resources available before the war. It wasn’t until the end of the war that the rougher products appeared. Having lost the war, Japan was ordered to get rid of all weapons, like fighter planes, but instead of handing them over to the Allied Powers, all their various parts were recycled for civilian use. Between 1946 and 1948 there was a rush to get hold of aluminium and similar materials to turn into tools and objects for daily use. Most of these objects were produced in small local factories and by individual artisans: industrial designers did not exist. These goods were produced out of necessity, which kept the design element to a minimum, so you have all these plain items devoid of any ornamentation or engravings. People were not after beautiful things; they only wanted sturdy useful products, and these are the objects I collect. I don’t like them just because they’re old. As a designer who always tries to keep things simple, I’m fascinated by a time when craftsmen used to make their products without bothering about design. That’s why I like these simpler, smooth objects whose only purpose was to make our life easier. They are perfect in their simplicity.

Japan has a long tradition of reclaiming and reusing materials, hasn’t it?

O. S. :Yes, this passion for recycling was born out of necessity, as Japan is an island nation with a large population and few mineral resources. As I said, during the war and in the post-war period, objects that would normally be made of steel, wood or ceramic were produced in aluminium, and even today Japan is the world leader in the recycling of aluminium cans, because it’s a material which is expensive to manufacture, but very easy to process.

You could say you are interested in old-style zakka?

O. S. : Yes, even though I prefer to call them jitsuyohin (practical everyday articles). Since the mid- 1960s the term zakka has acquired a rather ambiguous meaning, and it’s applied now to the most disparate objects. Design has replaced functionality as the main requisite, and many of these things are just good looking knick-knacks of little or no practical use. For me zakka still means a daily necessity. That’s why I prefer now to call them jitsuyohin.

I guess the objects you collect don’t have any intrinsic value?

O. S. : No, not really. Objects made of iron or copper are highly valued, but nobody has ever used aluminium to make antiques. On the contrary, the things I look for are treated like junk. You see, aluminium is a very humble material. Now, ironically, people are beginning to take notice again. Once you reject the fad surrounding objects that are just cool and attractive in the short term, they become a simple and valuable testimony to the idea of meaningful interaction with material things. Particularly when you clean them of any paint and decoration, you’re left with their naked form and essential function. For me, this purity symbolizes the typical material- specific workmanship and refined simplicity of Japanese design.

Where do you look for these objects?

O. S. : There are a number of flea markets in Tokyo where one can find them, with a bit of luck. In Saitama Prefecture, where I live, I often go to such events. For example, Kawagoe City’s main shrine, Hikawa Jinja, holds an interesting market called Goenichi. When people renovate their family’s old houses, for example, a lot of old useless things are cleared out. Most of the time they just throw them away, but some good folk may decide to sell them at a flea market instead. The problem is that in Tokyo it’s almost impossible to find pre-war houses now, so I have to broaden my search to other regions and the countryside. I used to hunt for aluminium goods myself. Even now I visit the local markets and second hand shops every time I travel for business. In the past I’ve even paid visits to older people who used to hoard things compulsively and threw nothing away. Even now, I call tradesmen all over Japan, such as plasterers, because some of them still use aluminium tools that can’t be found anywhere else. People are acquainted with everyday utensils such as kettles or hot-water bottles, but there are so many aluminium objects out there that only professionals know about and use.

Why do you think it is important to show your collection widely?

O. S. : The traditional Japanese attitude of respect towards nature and the sustainable use of its resources has long been replaced by a rampant consumerism matched by few other countries. However, people never forget beauty in their daily lives, even when they are facing extreme hardship and poverty. By exhibiting these humble objects, I hope to make people think about our traditional values.

Interview By Jean Derome

Leave a Reply