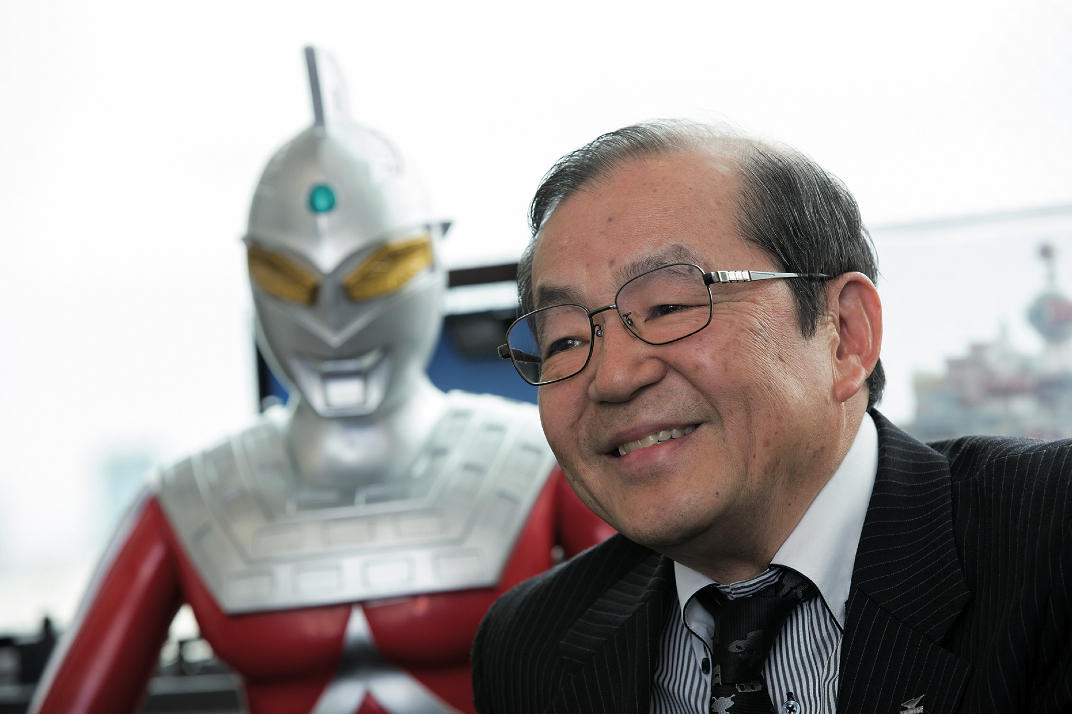

after playing the key character in Ultraman’s first series, kurobe Susumu still remains very popular 50 years later.

Since the beginning of the Ultraman saga 50 years ago, many actors have played Ultraman’s human alter ego, but few people can compete in popularity with Kurobe Susumu, aka the original Hayata Shin, the most well-known member of the orange clad Science Special Search Party. Now 76, Kurobe is still very active, and in 2012 he even reprised his old role in the Ultraman Saga feature film. Zoom Japan met Kurobe at the headquarters of Tsuburaya Productions.

When did you decide you wanted to work in film?

Kurobe Susumu: When I was in my third year of university. In high school, of course, I loved films and would often skip school in order to go to the cinema. I particularly liked jidaigeki (period dramas) featuring such stars as Misora Hibari and Ichikawa Utaemon. But even before that, in junior high, I remember watching a local youth theatre performance. I believe that was the very first time I thought I wanted to become an actor.

So how did you finally manage to be hired at the giant production company, Toho?

K. S.: Before Toho I belonged to a theatre group while I was still in college, but we didn’t have a lot of success. At the same time, I also had problems at home. These came to a head when my family disowned me, leaving me penniless in Tokyo. So I dropped out of school and began to look for a way to earn some money, until finally I began to work as a shoeshiner. It was at that point in 1961 that I was scouted by a film director who brought me into Toho.

Please tell me about the beginning of your career.

K. S.: I spent the first six months training as an actor. After that I began to appear in the movies, but at first only as a passersby or part of a crowd. I just had to walk in front of the camera or stand in the background without saying a word. I really cut my teeth at the lowest rank possible. Luckily I caught the eye of a producer, who arranged for my real debut in 1963.

What kind of parts did you play?

K. S.: Anything they wanted me to play, from teen films to yakuza flicks. You see, at the time we didn’t have an audition system. The actors were just assigned to this or that film and we had to do what we were told. We were just company employees and obeyed orders from above. Interestingly enough, one of the first films I appeared in was Kokusai himitsu keisatsu: Kagi no kagi (International Secret Police: Key of Keys) (1965), a parody of James Bond-style spy movies, footage from which was later used by Woody Allen for his directorial debut, What’s Up, Tiger Lily? He took some original scenes, rearranged them and added new scenes and dialogue.

Following the same studio system routine, in 1966 you were ordered to appear in the Ultraman series. What did you think about such a superhero? Did you think it was the right career move for you?

K. S.: First of all, I’d like to point out that when I was assigned to Ultraman, Toho broke a traditional studio rule. Until then, film actors were prohibited from appearing on TV because the small screen was considered as second-rate work compared to cinema. But when Toho produced the Ultraman forerunner series earlier that year, called Ultra Q, I appeared as a guest in one episode. So when I began as part of the Ultraman cast, I was already acquainted with the story. Anyway, to answer your question, on one hand it was just another acting job like the ones I’d done before. On the other hand though, sci-fi/monster films were a novelty at the time, so I was both curious and a little anxious about the final result. Honestly, I wasn’t completely sure the TV audience would like this kind of story. Then, of course, everything happened very quickly and the show’s audience rating shot all the way up to 42.8% in 1967, which was extraordinary. I think it was the result of the concerted efforts of all the people involved in the project. In particular, I believe a good part of Ultraman’s initial appeal can be found in the face/mask that was designed by Narita Toru. It had an almost divine quality. It reminds me of Kannon, the Buddhist deity of mercy, and though Ultraman’s overall appearance has somewhat changed over the years, the face has more or less remained the same.

For many people at the time it must have really been something special?

K. S.: Of course, it was something extraordinary, especially for the children who were our target audience. In those days, kids didn’t have a lot of toys like today, and enjoyed simpler games. Just to show you how crazy they were for Ultraman, most houses at the time didn’t have a private bathroom, so many people used to go to the local sento (public bath) after dinner. Well, come 7.00pm you couldn’t find even one kid at the sento because they had all run home to catch Ultraman. That’s one of the reasons why those old fans have stayed loyal to Ultraman, even after growing up, and now, 50 years later, they still enjoy the stories and share their passion with their children, or even grandchildren.

What was it like working in Ultraman in 1966? What were some of the challenges you had to face?

K. S.: On the one hand, as I said, acting is acting and there isn’t a lot of difference between films and TV. But on the other hand, the five members of the Science Special Search Party (SSSP) had to fight against giant monsters and, because the monster scenes were shot in a different studio, we had to pretend we were looking at these aliens. So we had to make sure that everybody was looking in the same direction. Also, all episodes were recorded without sound and we had to overdub our voices in post-production. This was also a challenge because of the limited technology at the time. Today, even if you are a fraction of a second late in reading your lines, they can easily synchronize your words with the images, but 50 years ago it wasn’t possible, so if we made a mistake we had to start all over again. I also remember the scripts we had to memorize had a lot of kanji and difficult words, and sometimes we had problems reading them (laughs).

What was the atmosphere like on the set?

K. S.: It was great, and our group of five was very close. Obviously we were very serious on the set and always tried our best, but we were also young and fun-loving. Captain Muramatsu and Arashi were in their early 30s, I was 27, Ide was one year younger than me, and Akiko [Fuji] was still only 20. We could never wait for the shoot to end so we could go out drinking together (laughs)!

I bet many strange and funny things happened during the shoots.

K. S.: Yes, and some of them were not very pleasant. For example, episode 20, Terror on Route 87, is when Ultraman battles a supernatural kaiju called Hydra. The story called for a night shoot in Saboten Koen (Cactus Park) on the Izu peninsula. The monster appeared and I was standing near a cactus pointing my gun at it, when suddenly I lost my balance and fell on the cactus. I had to pull down my trousers while crew and cast pulled the thorns out of my backside by torchlight.

Was it difficult working for Tsuburaya eiji, the creator of Tsuburaya Productions? How was he on the set?

K. S.: We actually never worked together. He was in charge of the special-effects studio and didn’t really meddle in the drama side of production. The two studios were two separate entities, and it was only in the editing room that the two parts were put together. By all accounts, Tsuburaya- san was a very kind man, and I think the other members of the SSSP did actually meet him a few times, but I myself never really had a chance to talk to him.

At the time the studio was located in Setagaya Ward in the southwest of Tokyo, wasn’t it?

K. S.: Yes, the two studios (the one where I worked and the special effects one) were a 15- minute walk from each other. The so-called Bijutsu Centre (Artistic Centre) in particular was nothing but a corrugated iron roofed barracks. It was very primitive. You could hear any kind of noise coming from the outside, like the rain falling on the metal roof, which meant we couldn’t work on any overdubbing.

You have appeared in many Ultraman TV series and films through the years. How do you feel about the way the Ultra Series has changed over time?

K. S.: As you know, Tsuburaya Eiji was a special effects pioneer, and even today the Japanese tokusatsu genre is famous worldwide. Of course, CGI is now an essential part of SF production, but I think the early work was so popular because of its analogue, hand-made character. It had a warmth that can’t be replicated with a computer.

American superheroes never die and never get old, while in Japan important characters actually disappear, never to return. even that first series in 1966-67 ends when Ultraman is mortally wounded by an alien called Zetton before Zoffy (his superior) comes to the rescue and saves his life. In the West this would never be acceptable. Why do you think Japanese dramas and films work this way?

K. S.: I really don’t know why. To be honest, I’ve never thought about it. But you’re right. While the original series ends with Zoffy carrying Ultraman away and Hayata – my character – having no memory of what had happened since their first encounter, the English version states that Ultraman will return, AND that Hayata remembers everything and awaits Ultraman’s return. Actually, according to the original plan Ultraman was supposed to last longer, but because of the great deal of work needed to make each story it was eventually decided to end the series after 39 episodes. That’s why the ending feels a little awkward.

INTERVIEW BY JEAN DEROME

Leave a Reply