Situated on the outskirts of the capital, this old industrial site is full of beautiful surprises.

“Next stop: Hamakanetani”. On hearing that announcement, the tourists on board the train gear up. Some get a camera out of their bag, others a map. This rather rough ride, which has taken over two hours from Tokyo, is about to end.

As soon as the train stops, people get off and exclaim with amazement. A huge cliff, its summit covered in lush vegetation, looks down over the station. On the right hand side, the sea reflects the playful rays of the sun, and from the beach the lingering smell of barbecued seafood tickles the nose. Eagles circle and glide through the blue sky, their wings almost motionless.

Nokogiri Yama, “saw mountain” in Japanese, situated on the west coast of the Boso peninsula, is one of the largest remains of the ancient Japanese industry of stone quarrying. It supplied volcanic tuff to the capital by boat from the 18th century until it closed down in 1985. Since then, it has become a tourist destination offering panoramic views from its summit. From there you can make out the Tokyo Sky Tree building in the distance, as well as emblematic Mount Fuji beyond Tokyo Bay. Amongst the list of local attractions, there’s also an old Buddhist temple hidden on the side of the mountain, with a 30-metre-high stone Buddha, as well as seafood and hot baths.

There are two ways of reaching the summit: hiking tracks for the bravest, but if you are not one of those, there’s a cable car. This 5-minute ride through the air, just above the treetops, allows you to see this industrial heritage site at close hand, once where men dug the soil from the bottom to the top of the 330-metre-high hill. With binoculars, you can see the traces they left behind and imagine how they worked the rock, chiselling it to break off chunks of stone. At the summit, a little exhibition takes visitors through the site’s history and its close connection to the city of Kanetani.

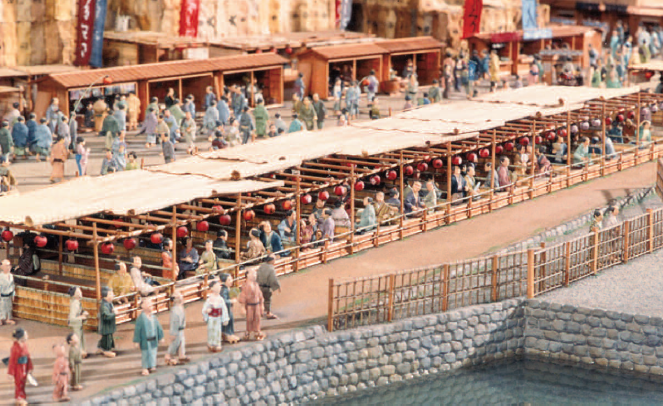

Tuff extraction started in the region to supply the needs of the rapidly expanding capital, then known as Edo, when it already boasted a population of a million. The dark-grey stone was particularly appreciated for its heat resistance, and became the basis of the local economy. The quality of the stone found at the top of the hill was better than at its base, so workers gradually worked upwards. Nokogiri Yama’s unusual shape – it looks like a giant has used an axe to cut through it vertically – testifies to the hard labour of the countless hands that sculpted it. They also constructed narrow precipitous pathways to connect the harbour to the summit, up and down which men and women toiled ceaselessly, their backs bent double, carrying the quarried stone. In the history of Japan, this quarry is as important as other industrial heritage sites such as Ashio’s copper mine (Tochigi Prefecture) and the Imperial saw mill of Yahata (Fukuoka Prefecture). The tuff extracted from Mount Nokogiri was used throughout the country, from the foundations of Yokohama Harbour to the construction of a pavilion in the Imperial Palace. The development and the modernization of the country were based on these volcanic ashes, which are several million years old, and had become hardened under the pressure of time and the fickle movements of the earth before being extracted by strong hands.

Nevertheless, the golden age of Kanetani’s industry was short lived. The 1923 earthquake that destroyed the capital and killed 100,000 people, revealed the fragility of tuff. It was gradually replaced by concrete. Its extraction was stopped permanently in 1985. To view these industrial remains where 80% of the local population were employed, you need to get to the summit. From the cable car station, the walk is short but steep. The climb up the steps and the view of the vertiginous drop will make some feel light headed, while others will be alarmed. The Japanese used to call this view: Jigoku-nozoki (a view into hell). “Oh, it made me shiver,” says one tourist walking towards the cable car. Another, holding binoculars, asks him to wait. She’s looking for Mount Fuji, a little grey triangle that you can just about make out in the distance, beyond the stormy mountains and the blue line of Tokyo Bay. From here, you can also see where the quarrying stopped, as workers left some outcrops of worked stone on the cliffside, perhaps thinking that they would be back later to remove them. But that time never came.

As suggested by the rather anachronistic nickname given to this view – the word “hell” has lost it’s previously demonic connotation – the location has been attracting visitors for a very long time. After being amazed by this unusual view, tourists can visit the temple on the hillside that boasts one of the country’s biggest Buddhas. Since it was founded in the 13th century, the Nippon- Ji (Japanese temple) has seen the comings and goings of both workers and visitors. It survived many wars and armed conflicts during its history until 1939, when a fire started by a tourist reduced it to ashes. The main pavilion, with its many hidden treasures and historical archives, went up in smoke. It was a nightmare for the monks who had to wait until the 21st century for their temple to be rebuilt. Due to a lack of money, parts of the site still needs to be restored, such as the 1,500 buddhas that are lined up along the hill’s pathways. Some of these little stone figures dating back to the 18th century are missing their heads, though that’s not due to the fire, but anti-Buddhist politics at the end of the 19th century, whose aim was to make Shintoism the state religion. These grey statues portraying a variety of expressions weren’t lucky enough to be restored like the big Buddha, whose face had become worn down by wind and rain and was renovated in 1969.

Tourism isn’t only needed to pay for the restoration of this religious site. After the quarry closed down, just as in other places, the area became a victim of depopulation, and it’s now looking to tourism to boost its economy. 40,000 visitors use the cable car each year, and there are as many hikers, but the local authorities consider this to be too few visitors to this religious and industrial museum. “We’re very bad at communication,” says Suzuki Hiroshi, the president of the Kanetani art museum, regretfully. “We have more and more foreign tourists, we should display signs in English,” he adds. Tours and conferences about the complex history of this site are organized with the hope of reaching a total of a million tourists in a few years time. With the increasing number of foreign visitors to Japan, you can already hear English being spoken at Hamakanetani station. The future seems promising.

Yagishita Yuta

Leave a Reply