The phenomenon that excited curiosity and fascinated collectors in the West has had a remarkable evolution.

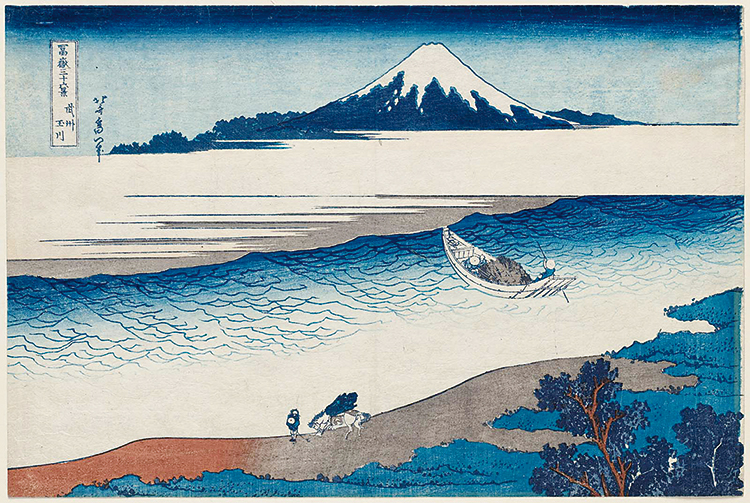

The River Tama in Musashi Province (Bushu Tamagawa), from “The thirty-six views of Mount Fuji” (Fuji sanjurokkei), 8th view, around 1829-1833, by Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849). Woodblock print (nishiki-e); large landscape format (oban yoko-e).

Japonisme can’t be mentioned without emphasizing the role played by Japanese prints. Western artists would never have created art in the way they did without having discovered them. The beauty of the drawing (with brushes and Indian ink), the colours, sometimes with a scattering of powdered gold or silver, and the originality of the themes of these multi-coloured prints, were an unending source of inspiration to them.

In Japan, the technique of woodcut printing, introduced from China, was used in the first place to illustrate Buddhist texts, then for all kinds of printing. It had a revival in the 17th century when the painter Hishikawa Moronobu used it, in around 1660, to made the first black and white wood-block prints, called sumizuri-e, on separate sheets using Indian ink.

But customers tired of black and white, and wanted to buy coloured prints. So they were enhanced by adding an orange colour, tan, by hand, which was made from sulphur and mercury. Later on, from the start of the 18th century, these prints known as tan-e were joined by others enhanced with a purer red colour made from safflower (Carthamus tinctorius), called beni-e, as well as prints called urushi-e, using a black lacquer made from Indian ink mixed with animal glue, nikawa, which gave them a shiny finish.

Towards the middle of the 18th century, prints began to be made with two or three different colours. These were called benizuri-e, and marked a step forward, which led, in around 1765, to multi-coloured prints, (nishiki-e), or “brocade pictures”, originally created by Suzuki Harunobu.

To this day, Japanese printmaking remains a team effort involving the painter or illustrator, eshi (the term “artist” didn’t make an appearance until the Meiji era, 1868 – 1912), the engraver, horishi and the printer, surishi. The publisher, hanmoto would chose a painter according to the subject matter he wanted to depict or for whom the prints were aimed. Apart from the surimono, privately commissioned wood-block prints for special occasions, which used the most luxurious paper and colours, the prints were created for commercial use. To be successful, the publisher had to sell as many prints as possible of a quality that corresponded to the criteria demanded by the prevailing fashion. A print was made two hundred copies at a time, and if it was popular, up to a thousand or two thousand copies were printed.

The publisher asked his chosen painter to make a drawing, hanshita-e, always created using a brush and Indian ink. If he was satisfied with the result, he would show it to the wholesalers and specialist shops, which sold prints and illustrated books, Ezôshiya. After 1791, each print had to display the censor’s seal. The publisher submitted the drawing to the authorities to obtain a seal, aratame- in, without which he was unable to produce or sell the print.

The painter would then send his choice of colours to the publisher who passed the drawing to the engravers. They would have the delicate task of etching the design as carefully as possible and in the minutest of detail. Xylography is a technique of engraving in relief, which needs the part to be printed to stand proud of the wood. The thick hair of Utamaro’s famous beauties sometimes necessitate a depth of a mere half-millimetre, so it demands infinite patience and great dexterity. A first impression of the print would be shown to the publisher and the painter who then decided whether it needed any corrections or if they could go ahead and print the first batch, the most beautiful of which are the most sought-after today. The printer was given the same number of woodcut blocks as there were colours to apply. The sheet of traditional Japanese paper, on which liquid solution had been added, dôsa, made of alum and an animal- based glue, which allows the colours to adhere easily, was then applied. The sheet of paper was placed on the engraved block of wood, kento. Using a burnishing pad, baren, made by the printer himself, he carefully burnished each colour one at a time.

The price of prints varied according to their size, the quality of the pigments used, etc., but they hardly ever cost more than a few euros in today’s money. A hundred were printed (by hand, without the help of a press), then if they sold well, up to two thousand copies were printed, a great number for the period. They were aimed at everyone of whatever social class. Warriors or other rich feudal lords who could easily afford paintings, still bought prints, as did the less privileged. The prints were popular, but Utamaro, Hokusai, Hiroshige and the other great print makers, would never have guessed that they could have commanded such high prices a century and a half later.

B. K.-R.

![No51 [MEMORY] A writer who cannot forget](https://www.zoomjapan.info/wp/wp-content/uploads/focus02.png)