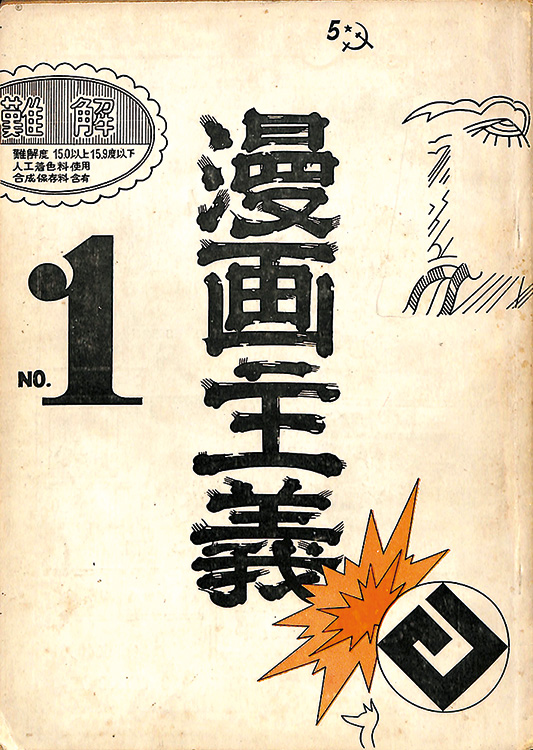

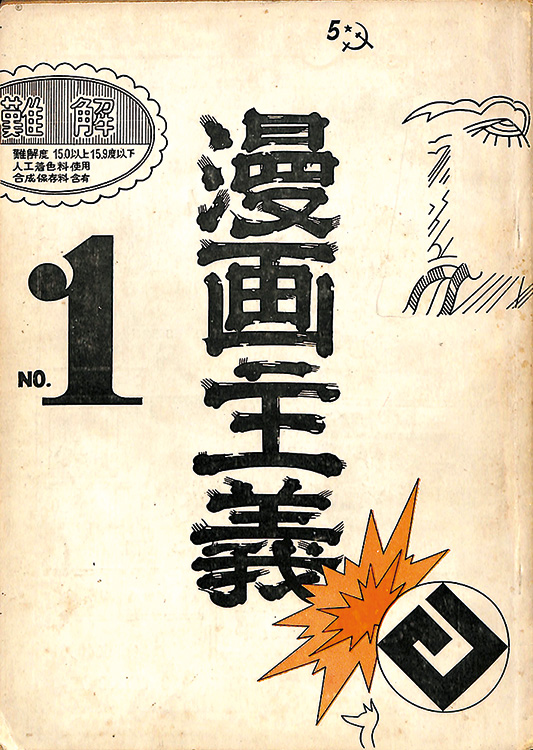

The first issue of Manga shugi (March 1967) was almost wholly devoted to Tsuge Yoshiharu.

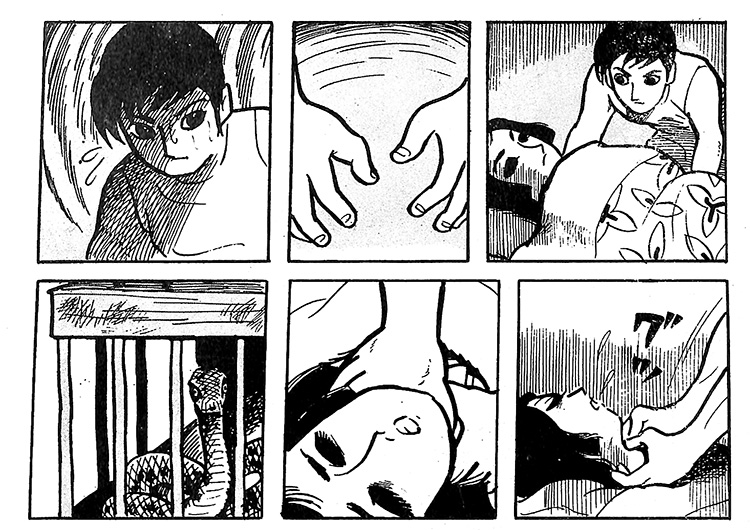

The work of Tsuge Yoshiharu was influenced by his experiences as a traveller. Takano Shinzo tells us about them.

The name of Takano Shinzo may not mean much even to hardcore manga fans, but in the last 50 years he has done a lot for Japanese comics both as an editor and essayist. While artist Shirato Sanpei and editor/publisher Nagai Katsuichi are usually praised for co-founding the trailblazing alternative manga magazine Garo in 1964, Takano (who joined in 1966 as managing editor) is the one who actually oversaw the artistic content and did many of the interviews, turning the magazine into one of the most influential publications of the New Left. Then, in 1967, and under the pen name Gondo Susumu, he co-founded Manga shugi (Mangaism), arguably the world’s first journal devoted to manga criticism. When, in 1971, Takano felt that Nagai was no longer supporting his editorial vision, he left Garo and created his own periodical, Yagyo, which inherited many of Garo’s contributors. However, it wasn’t comics we talked about when we met at his office not far from Shibuya. In fact, Takano is probably the greatest expert on Tsuge Yoshiharu’s travels around Japan – an activity the Japanese artist started when he was around 30, and which resulted in a series of acclaimed travelogues besides forming the inspiration for his tabi-mono (travel story) manga.

Tsuge is often said to be a difficult, very private person. What was it like when you first met?

TAkAnO Shinzo: I was introduced by Mizuki. Apparently, Tsuge was intimidated by me because, at the time, I was already working for the Japan Reader’s Newspaper, which had a rather large following, so he regarded me as a great intellectual. Anyway, I went to his apartment and spent a couple of hours talking about this and that. Tsuge did most of the talking… Well, actually there were many long moments of silence during our conversation, when we just smoked one cigarette after another. Still, you could feel that he was different from other kashihon mangaka (writers of rented manga). He could actually hold his own talking about literature and other things. Eventually it got so dark in the room that we could barely see each other (laughs).

So eventually he got used to you.

T. S.: Yes, I guess you could say so. He understood we were similar – we were both loners, had no friends, but were not sad about that – and shared the same interest in travelling. So when I later joined Garo, I had no problems working with him.

Speaking of journeys, for a long time you both travelled around Japan, often visiting the poorest parts of the country in search of god-forsaken villages and dilapidated mountain onsen (hot springs).

T. S.: Actually, during my student years, I was attracted to more classic tourist locations such as Kyoto and Nara. I was into history and liked to visit temples. Tsuge, on the contrary, has always been obsessed with the places where nobody goes, like when he used to travel with Tateishi- san, another kashihon manga artist. Some of these desolate places have actually become famous (well, sort of) thanks to Tsuge. There’s an onsen I visited two years ago where the locals have organized a Tsuge-related event for two years in a row.

Have you ever travelled together?

T. S.: Unfortunately not. I think we always feared the other one wanted to be alone, so we never gathered enough courage to say the words: let’s go together. He probably thought I’d be trouble, and have my own ideas about travelling. Other people, like magazine editors and photographers, did accompany him mainly because it was work related, or they just left every decision to him and followed him around wherever he went.

Starting in 1976, Tsuge began to write a series of travel pieces for new poetry magazine Poem, whose editor – and poet – Shozu Ben often followed him around Japan. Shozu later said that though Tsuge seemed to enjoy his company, he probably wished he could travel alone.

T. S.: Solo travel was certainly what Tsuge enjoyed the most. Although, as a matter of fact – this is something not many people know – he rarely travelled alone. For example, when he wrote for a magazine, like Poem or Asahi Graph, he had to go with an editor and photographer, which sometimes resulted in an awkward atmosphere between Tsuge and his travel companions. It was completely different in the case of his friend Tateishi. They’d known each other since the kashihon period, when they were in their early 20s. They often travelled together and every time, without fail, ended up fighting and parting ways after a few days (laughs). Tsuge’s wife used to say, “Why go with Tateishi if you quarrel all the time?”

In the autumn of 1967, Tsuge undertook a long trip around Tohoku, in the north-east of Japan. This trip left a lasting impression on him and inspired his later tabi-mono. How were these two things related?

T. S.: Tsuge had been reading books about Tohoku and other regions, and was fascinated by those travelogues. He spent about one week visiting such places as Hachimantan and Iwase Yumoto for the first time, and was surprised not only by the landscape but by the kind of people he found there – mainly elderly people who had retained a purity and warmth of character that was missing in inhabitants of big cities. His discoveries clearly went far beyond his expectations and left him hungry for more. That’s why he tried later to replicate the same kind of experience while exploring the Japanese Alps and southern Japan. I remember when he returned from that first trip to Tohoku. He was so eager to talk about his wonderful adventure that he came straight to my place, that night, still carrying his backpack and hiking gear. The interesting thing was that, while listening to him, the way he explained things, you could picture the stories he would later turn into comics. Of course, this doesn’t mean his stories are simply a dramatisation of his travel experiences. He usually came up with a story idea first, and only later added as locations the places he had photographed, or introduced a few reallife episodes. So to answer your original question, while these comics are called tabi-mono, they are fundamentally works of fiction. The funny thing, though, was that many readers took them at face value. Shiina-san, for example, was a writer who also travelled a lot. He used to say, “In all my travels, I’ve never had such interesting experiences as Tsuge.” Of course, they were the result of his creative imaginaiton!

Sometimes people want to believe that a certain incident has actually happened, don’t they? And in Tsuge’s case, many of the details featured in his travel comics are true, which adds an additional level of realism.

T. S.: You’re right. Even now many Tsuge fans visit the onsen he made famous, looking for traces of his comics. And funnily enough, the ryokan owners themselves believe that everything he wrote was true, and in turn repeat those stories to their guests without realising that they were just a figment of his fertile imagination. In a sense those stories have become part of local mythology.

Why do you think Tsuge was so attracted by those decaying, seemingly unappealing places?

T. S.: Everything goes back to his childhood years, which, as you know, were far from happy. These countryside onsen and mountain villages reminded him of his hometown. Not literally, of course, because he mostly grew up in Tokyo, after all. But they share the same atmosphere; they resonated within him. He wasn’t so much interested in the landscape itself as in the people who lived there, for whom he felt a genuine empathy.

It’s also true that in many of his writings he said he longed to hide in such places; to leave everything behind and disappear.

T. S.: When he was a teenager, he even tried to board a ship to America – not once but twice. He had no plan whatsoever. He only knew that he wanted to disappear. Even now, he says he wants to live quietly and undisturbed. Of course, it’s just a dream, a sort of private utopia. You only have to point out that living up a mountain is impractical – especially for someone like him who doesn’t even have a driving licence – to bring him back to reality.

How did he choose the places to visit in Japan?

T. S.: He was a fan of ethnologists Miyamoto Tsuneichi and Yanagida Kunio, and religiously read all their works. He had the Nihon Chiri Taiken (NCT) (Experience Japan’s Geography) series too. Those books were his main source of inspiration. The NCT volumes featured tiny grainy pictures of each place. They didn’t appeal to me at all, but somehow he looked at them and was able to choose where to go next. I guess he saw something in them I couldn’t see.

You’ve been to many of the places that Tsuge featured in his comics. What were your impressions at the time?

T. S.: I understood why Tsuge loved them so much. In other words, visiting those places (Kita Onsen especially comes to mind) is like getting to know the man himself, his mind and soul. Of course many of those places have changed, the ryokan have been torn down and rebuilt, so it’s difficult to recapture the original feeling, but they’re still worth checking out.

How about Chiba, where he spent part of his childhood and set many of his stories?

T. S.: Many of the original locations are still there. Again, Chiba is a very plain, unglamorous prefecture. That’s why Tsuge likes it so much. In Futomi, where scenes from “Neji-shiki” are set, the local government has put up a plaque where Tsuge’s name, Yoshiharu, has been misspelled [the second Chinese character is wrong]. People have pointed this out, but apparently the authorities have no plans to replace the plaque. “Neji-shiki”, of course, is a surreal, dream-like story, but even in a more realistic story such as “The Nishibeta Village Incident” you can see Tsuge’s creativity in action. A patient from the local mental hospital, for example, really did escape before Tsuge visited, but the story he tells is completely different. Also, the guy who actually got his leg stuck in a hole in the ground was not the escaped patient but comic artist Shirato who was travelling with Tsuge.

How has your approach to travelling been affected by Tsuge?

T. S.: I used to visit hot springs even before meeting Tsuge, but because of his travels I began to seek out the same kind of unpopular onsen he preferred. In some cases the pupil has even surpassed the master: for example, he’s been three times to Kita Onsen, in Tochigi Prefecture, but I’ve been there ten times (laughs). Even when I take pictures, I feel like I disappear and see things through his eyes. In the end, I’ve become more Tsuge-like than the man himself.

What’s the difference between Tsuge the comic artist and Tsuge the travel writer?

T. S.: It’s the difference between fiction and reality, art and documentary. His travel essays read like a diary, they detail what he did and what he saw, the people he travelled with and those he met. Sometimes, he stops to meditate on something or take in a particularly poignant scene, so there’s also a certain element of philosophy in his travel writing. The comics, on the other hand, are pure literature.

Do you still see Tsuge sometimes?

T. S.: Of course. He’s the kind of guy who literally keeps talking for hours. Most people eventually get tired of his sometimes philosophical sometimes nonsensical ramblings, but I love to listen to him, so I guess we complement each other well.

INTERVIEW BY J. D.