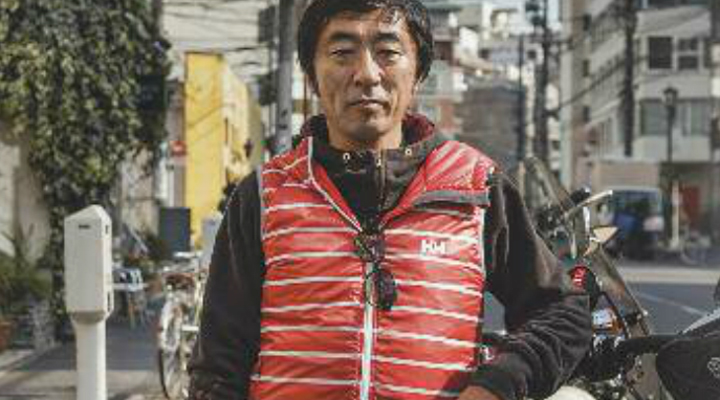

Nikita, 28, takes a break between shifts at Soapland Paradise, in Kawasaki.

Nikita, 28, takes a break between shifts at Soapland Paradise, in Kawasaki.

Despite being banned, prostitution continues to thrive with the existence of particular establishments.

Look for Yoshiwara on the map and you won’t find it. Officially, the name does not exist anymore, the district having been renamed Senzoku 4 Chome, in Taito Ward. The area itself, though located in central Tokyo (not very far from Asakusa’s tourist attractions), is cut off from the rest of the city as it is relatively far from any train or subway station, and nobody ends up there by chance. To put it simply, it is one of those districts that both the authorities and most Tokyo residents try not to think about. But official topography aside, everybody knows Yoshiwara; even those people – the great majority – who have never set foot there. After all, this land of carnal pleasure has been there for more than 400 years.

Yoshiwara, together with Kabukicho, is one of Tokyo’s and Japan’s most famous red-light districts. But while in Kabukicho these “naughty” places share space with eateries, cafes and even a multiplex, Yoshiwara’s quiet streets are just row upon row of soaplands and brothels, occasionally interrupted by a convenience store, cheap hotel or the odd shop catering for the local working population. There are so many, in fact, that they occupy four full city blocks.

Each entrance is guarded by at least one darksuited male tout. In the past, they might have tried to lure passersby inside, but with the advent of the internet, most clients now make reservations in advance, so the main job of the guys in the street is to welcome customers and keep unwanted people away. This includes foreigners. But though Japan may be trying to lure as many Asian and Western tourists as possible, so far, and with few exceptions, the sex industry has failed to attract foreign currency.

Another thing that distinguishes Yoshiwara from Kabukicho and other similar districts is its drab and undistinguished character. Seen from the outside, all those grey, anonymous-looking exteriors are hardly picture-worthy. So if you plan to add some salacious photos to your Instagram page, save yourself a trip to Senzoku and look elsewhere. Even inside, things don’t improve much. Gone is the elegance and pageantry of the good old days, when high-ranking oiranwelcomed their customers wearing gorgeous kimonos. Today’s soaplands, in contrast to hostess clubs (at least the high-end Ginza bars), are gaudy, often tacky places. After all, their customers couldn’t care less about their interiors and atmosphere. They are not interested in chandeliers, an air of sophistication, or intelligent chit-chat. They only want one thing and one thing only.

Yoshiwara soaplands are the result of the meeting (or the mating, if you prefer) of two different strands of social history: public bathing and mercenary sex. Let’s have a look at the former first. The original models for the Japanese public baths were born in India and arrived in Japan through China in the Nara period (710-784). At first, they could only be found in Buddhist temples and were exclusively used by priests and the sick. In fact, we have to wait until the Kamakura period (1185-1333) to find the first mention of a commercial bathhouse. Like their religious predecessors, these mixed-sex establishments were closer to steam baths as there were no taps on the premises and each customer only received a small ration of water.

Things became “interesting” between the 16th and 17th centuries, when bathhouses added a second floor where guests could relax and enjoy a cup of tea after their bath. They even began to hire female attendants who first washed the guests’ backs, then joined them on the second floor after working hours to entertain them playing the shamisen and performing magic tricks. The government tried to ban this practice more than once during the Edo period (1603-1867) and finally succeeded in 1841, when the bath attendants were forcibly moved to Yoshiwara, by then the city’s official red-light district. Finally, the banning of mixed bathing in 1890 put an end to the selling of sex in public baths.

However, it takes more than laws and rules to stop people’s desire to have a good time. Fast forward to 1951, when a massage parlour called Tokyo Hot Springs started offering individual Turkish steam baths. Similar establishments popped up all over the country, and in no time, the so-called Miss Turkeys who staffed these private rooms began to offer a variety of more titillating services.

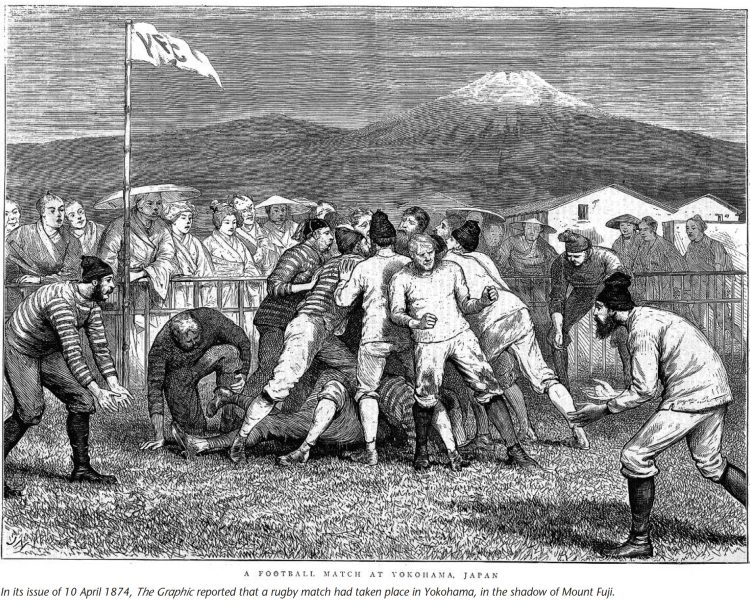

The so-called shasei sangyo (ejaculation industry) has thrived in Tokyo since future shogun TOKUGAWA leyasu made the place (then called Edo) his capital. Planning to turn the small village into a city, Ieyasu ordered large-scale construction work including land reclamation of Edo Bay, river improvements, the digging of new canals and moats, and a system to supply the city with water. The construction rush attracted tens of thousands of men, so much so that by 1733, according to government records, out of a population of 540,000, only 200,000 were women. These figures, moreover, did not include the 500,000- man strong samurai contingent.

Room where men select the young women at Soapland Paradise, in Kawasaki.

Room where men select the young women at Soapland Paradise, in Kawasaki.

By this time, the Yoshiwara red-light district had been open for more than a century. First established in 1617, near Nihonbashi, in 1656 it was moved to its present location north of Asakusa (then the city’s edge) and promptly burned down – together with the rest of Edo – one year later. It was damaged again by fire in 1913 and nearly destroyed by the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake, but it was rebuilt every time and remained in business until prostitution was finally outlawed in 1958.

This, of course, is not the end of our story. Indeed, it’s just the beginning. Common brothels may have disappeared – or just went deep underground – but the officially innocuous Turkish baths were still around. Many of them moved into Yoshiwara and by 1960 were offering sex again. About ten years later, there were more than 200 in Tokyo and more than 1,000 across Japan.

As a humorous aside, the name soapland originated in 1985 after the Turkish Embassy in Tokyo started complaining about their country being associated with prostitution. Always careful not to run foul of the authorities, the 110-member trade association of Turkish bathhouse owners was quick to respond to the diplomatic crisis: with a brilliant stroke of genius, they held a nationwide contest to find a new name. Eventually, they got 2,200 suggestions, and the name “soapland” (the brainchild of a Tokyo office worker) came out on top.

Parking at a soapland in Kawasaki. Vehicle licence plates are concealed to ensure clients’ anonymity.

Parking at a soapland in Kawasaki. Vehicle licence plates are concealed to ensure clients’ anonymity.

Today, soaplands must fight the competition of a variety of often cheaper sex services (from “fashion health” massage parlours to pink salons), but their unique mix of bathing and sex still attracts a satisfying number of loyal customers. Though prostitution is still officially banned in Japan, these places remain in business because they are registered with the authorities under the classification of “private room bathhouse.” In other words, the customers officially pay only to have an assisted bath. What happens during or after the bathing is another story.

Technically, the girls are self-employed and rent their rooms from the soapland. They are either responsible for buying their own work equipment (lotions, condoms, towels, etc.) or the soapland provides them for a fee.

The police, of course, know why guys keep flocking to Yoshiwara, but they usually let them be as long as they keep a low profile. Once in a while, they come up with a reason to crack down on them, especially after some incident appears in the news. The other notable time when they made their presence felt was during the buildup to the 1964 Olympic Games. Aiming at showcasing a clean, wholesome country to the foreign visitors, the government decided to put the squeeze on those establishments that threatened to blemish Japan’s international image. At that point, the bath association came up with its own set of regulations in a show of “voluntary” self-restraint (never mind that the new rules were never carried out). Since then, the whole industry has gone with the tide, adapting to circumstances while striving to offer their clientele an impeccably “clean” service.

G. S.