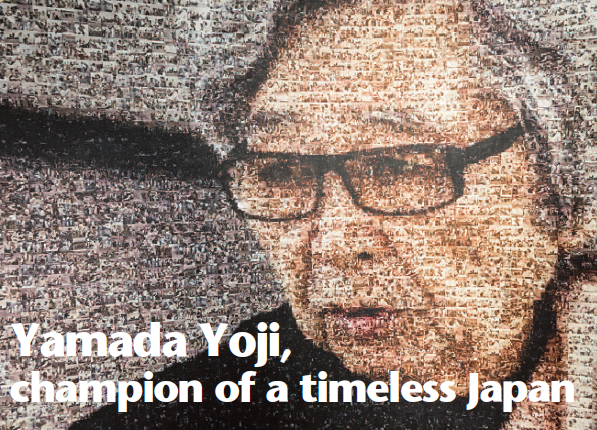

The famous columnist Kawamoto Saburo remembers this very important period for post-war Japan.

The famous columnist Kawamoto Saburo remembers this very important period for post-war Japan.

For 45 years writer Kawamoto Saburo has chronicled Tokyo’s past and present. Born in the city’s Yoyogi district 69 years ago, Kawamoto has witnessed all the main events that have shaped Japan’s capital through the years. Among them, he is particularly fond of the circumstances surrounding the 1964 Olympic Games. Kawamoto shared with Zoom Japan his reminiscences about those heady times, during a torrid August afternoon at the posh cafe inside Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel. “When Tokyo was awarded the Games in 1958, people’s reaction was rather mixed, but the more preparations progressed, the more popular enthusiasm grew, so much so that in 1964 at least 80% of the Japanese supported the event.” It was a very special time. Japan had been defeated in the Pacific War and for about ten years life was very hard for everybody, but then things began to improve and the Games came to symbolize the birth of a new Japan. Even more important than the sporting event itself, there was a well-thought-out national economic plan behind Tokyo’s drive to host the Games.

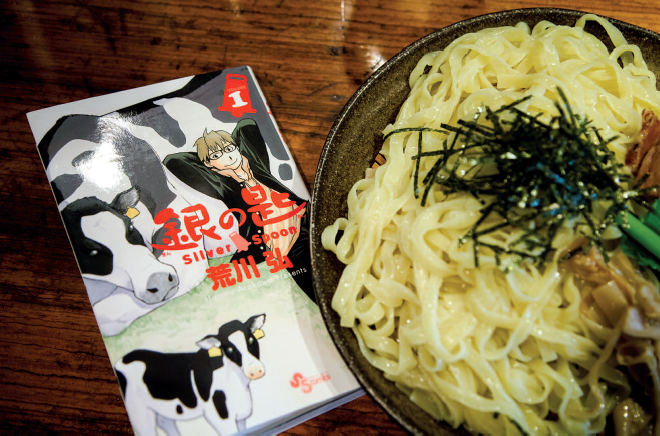

“For me the biggest changes were those that affected daily life the most. For example, many smelly rivers and canals were filled in and roads were built on them. But the greatest change of all happened in many people’s homes. It was around 1964 that ownership of the TV set, the vacuum cleaner and the washing machine became more and more widespread, and pit latrines were replaced with flushing toilets. This said, despite the developments at a macro-economic level, for most people everyday life didn’t really change. We still lived in wooden houses with tatami-matted floors, ate our meals sitting at the chabudai (low dining table), in other words our lifestyle was still far different from those of the American households portrayed in the dramas we used to watch on TV”. Speaking of foreigners, as many visitors were expected from abroad, the authorities issued a number of “suggestions” to the local population. “The most conspicuous being “Do not piss in the street” so that the nation wouldn’t lose face in front of the whole world (laughs). As for me, in 1964 I was 20 and a college freshman, and if you were a fun-loving guy there wasn’t a better place to be than Shinjuku, the western district whose station is used today by an average of more than 3.5 million people daily. There you could find many cinemas, jazz cafes, and especially MEETING The man who experienced the revolution The famous columnist Kawamoto Saburo remembers this very important period for post-war Japan. the ever-popular Kinokuniya bookstore. Of course I loved to read, but even more appealing to me was the record store on the second floor.

In 1963 the Beatles had brought about a musical revolution everywhere, including Japan, so as soon as The Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan or Joan Baez put out a new album, it was available in Tokyo too. You could say we were really experiencing a cultural revolution at the same time. “Then of course I would go upstairs and buy a copy of Heibon Punch. This magazine (“the magazine for men,” as they proudly declared on the cover) started in May 1964 and greatly contributed to the spread of youth culture in Japan. Until then youth had only been seen as the stage leading to full-blown adulthood. As such, the students’ role in society was negligible. But the Beat Revolution raised youth’s visibility, and Heibon Punch greatly contributed to shape our tastes in fashion and music while also covering such topics as cars and even sex. Up to the mid-60s, for example, most students used to wear their school uniform all the time, so they didn’t really have a chance to think about clothes, plus few of them could actually afford to buy any. But just around this time VAN became very popular in Japan, especially their button-down shirts. Writer Murakami Haruki even now still sports that same look (laughs)! One notable element of this magazine was its cover that in the beginning was always illustrated by Ohashi Ayumi. Even now after 50 years, her art looks very stylish. The fact that a woman illustrated the cover of a men’s magazine was in itself something special. It was thanks to her work that the professional figure of the illustrator came to the fore and became central to the creation of a certain cultural mood”.Kawamoto confesses that he feels increasingly estranged by the way Tokyo has changed in the last few decades. “Probably it’s because I’m too old now, but Tokyo has grown too big for my tastes,” he says. “Also, what at the time was seen as progress is now considered as a big mistake. Take, for example, filling in all those rivers; in the ‘60s that was considered a good idea. It was the ultimate sign of progress. You must take into consideration that Tokyo was in the midst of a pollution emergency. In particular, the many rivers had turned into smelly receptacles for refuse, their waters looked reddish brown and all the fish had gradually disappeared, so many citizens had welcomed the idea of covering them. But in retrospect that was a bad decision and things should have been handled differently. Of course it’s easy to judge the past when you are 30 or 40 years removed from those events. The same thing could be said for the city’s widespread tramway. Tram use reached a peak in the mid-50s, after which the Metropolitan Government began to close one line after another until in the first half of the ‘70s only the Arakawa Line had survived (and still operates to this day). Now many cities worldwide are adopting this system because it’s ecological, but in 1960s Tokyo, with the gradual increase of privately owned cars – the so-called “my car” boom – those trams were seen as a traffic-slowing nuisance. That was just too bad. I really love them…”.

Interview by G. S.

Photo: Kondo Keiichi