Contrary to appearances bicycles are ubiquitous in Japan. But there is more to be done.

The word “Japan” conjures up many different images: from kimono-clad geisha and sushi to martial arts and otaku culture. Bicycles, however, are definitely not among them. When it comes to cycling the first places that come to mind are the Netherlands or Portland, Oregon (the most bike-friendly city in the US), to say nothing, of course, the hundreds of millions of cyclists in China. Nevertheless, Japan is one of the world’s great cycling nations.

With a population of 127 million, Japan has 72 million bicycles, with over 10 million new bikes sold every year. Cycling in Japan has always been a popular means of transport, and even today it is particularly convenient for short trips and shopping locally. Indeed, the average bicycle journey is less than 2km. In Tokyo alone 14% of all trips made in a day are made by bicycle. Though 14% may be a rather low figure, especially when compared to other cities, considering Tokyo’s sheer size and the total number of trips made in one of the world’s most densely populated metropolises, this is a noteworthy achievement.

One of the main reasons for this low percentage is Japan’s famously efficient public transport system. With so many trains and buses connecting residential areas and suburban neighbourhoods with schools and the central business districts, commuting by bicycle is definitely not a priority. Another reason is that many companies actually discourage or even ban their employees from cycling to work (in order to avoid accident-related problems). This said, over 20% of Tokyo’s 20 million daily rail passengers ride a bicycle from their homes to the local station, as it’s faster and more convenient than walking or taking a bus.

In the last few years more and more commuters have been choosing bikes over cars and trains; partly as a way to keep in shape, partly to avoid traffic jams and the infamously crowded rush hour trains. And some work places seem to be happy about this, going so far as setting up bike parking and shower facilities.

The events of March 2011 greatly contributed to making cycling more appealing. The big earthquake that destroyed the northeastern part of Japan paralysed all transport systems in the Tokyo metropolitan area, forcing many people to either walk long distances to return home or spend the night in temporary shelters in the city centre. Commuting by bike is a good way to avoid getting stranded away from home in the event of a major disaster.

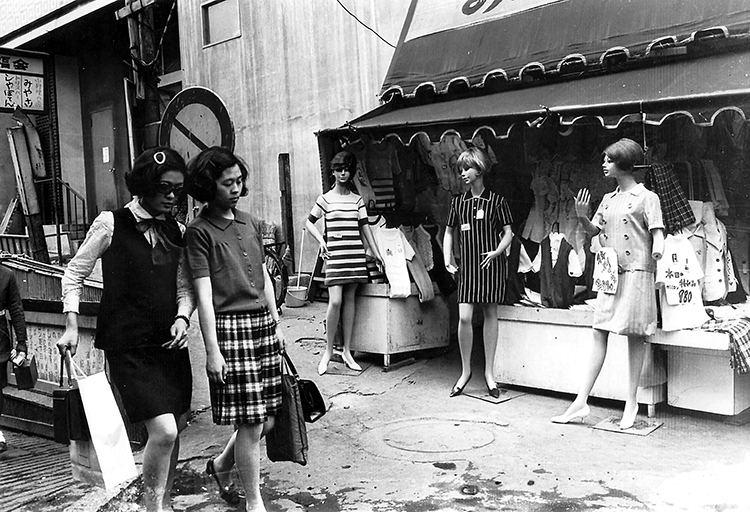

So why does cycling in Japan generally go unnoticed despite all those people using a bike on a daily basis? Probably the main reason is the attitude of the local cyclists themselves. While cycling is seen as a crusade against polluting cars, especially in Europe and the US, with activists even organizing Bike Pride and Critical Mass events, most Japanese consider riding a bike as just ordinary part of their daily life. Cycling, in other words, is not something to boast about, but a simple and efficient way to get things done, be it shopping, paying the bills, going to the doctor or taking the kids to nursery school.

Unfortunately bike culture in Japan still faces many challenges. For one thing, bikers are considered to be a nuisance by many people, both drivers and pedestrians alike. A recent rise in accidents involving bicycles has not helped cycling’s public image, and the police have become much stricter with cyclists. In addition the recent boom in fixies (fixed-gear, single-speed bikes) has been both a blessing and a curse: on the one hand owning a fixie has become a kind of fashion statement, creating a new interest in bikes and encouraging more people to buy one; on the other hand, however, all these inexperienced riders have flooded the streets and pavements in every major Japanese city, contributing to the aforementioned rise in accidents, especially those involving pedestrians and cyclists.

Although fixies are now the new cool thing to own, Japan’s most distinctive bicycles are the ubiquitous “mamachari”. Literally meaning “mum’s bike”, these heavy workhorses are the Japanese equivalent of the family estate car; practically every family owns at least one. These single-speed monsters can be incredibly slow and difficult to ride (they must be part of the reason why Japanese mothers are so lean, healthy and strong), and they are used to do all the heavy-duty work, from shopping, riding to the local station or taking the kids to school and the swimming pool. As each neighbourhood – especially in the suburbs – is a self-sufficient world where residents can find everything they need, a mamachari is a much better, more efficient option than a car given the lack of parking, narrow streets, and the relatively short distances one has to cover in order to reach ones destination.

Today bicycle manufacturers have come up with slicker, better looking models, even motor-assisted bikes for those who live in hilly areas, but the basic appearance of the mamachari has not changed in a long time: a top tube bent low (which is easy for women in skirts to step over), a shopping basket at the front, a luggage rack at the back, mudguards, chain guards, dynamo lights, an integral lock, a bell, and a hefty rear stand that keeps the bike stable and upright when parked.

They are usually quite cheap (they cost between 10,000 and 20,000 yen) and are essentially considered as disposable, like all those plastic umbrellas people buy for a few hundred yen and leave around everywhere. Mamachari are regularly left outside the house, exposed to rain, wind and snow, and their owners don’t know or just don’t care about bike maintenance, letting their bikes rust until they just throw them away and buy a new one. As Japanese mothers use their bikes to taxi little kids everywhere, mamachari often sport one, two, sometimes even three child seats. Watching these shaky pieces of rusting metal on wheels slowly moving through traffic is a heart-stopping sight, similar to a group of acrobats in a Chinese circus. Yet these fearless mums just get on with their daily business. When the government recently implemented a ban on carrying two children on a mamachari, mothers across Japan campaigned against the ruling and the government was forced to back down.

If the suburbs are relatively safe havens for cycling, cyclists have a much harder time navigating heavy traffic in the city centres. A metropolis like Tokyo, for instance, only has 10km of dedicated cycle paths – a ridiculously low figure when compared to Paris (600 km), London (900 km), or New York (1,500 km). Part of the problem is that the planning of cycling infrastructure is the responsibility of each of the 23 wards within Tokyo, leading to confusion and a lack of coordination. Just recently a few central wards have begun to create more cycle paths and even to offer a cycle sharing service.

Despite these problems one can definitely see more bikes on the road. As Brad Bennett (of the bike tour website Freewheeling) says: “People even go on dates by bike and hang out at Blue Lug bike shops at the weekend. Cycling in Tokyo is still dangerous, but it’s finally cool. And hopefully, elected officials will create a better infrastructure for pedestrians and cyclists throughout the country”. According to Australian-born Byron Kidd (one of the people behind the Cycling Embassy of Japan), “Japan is already leagues ahead of most of the world when it comes to utilitarian cycling. Cycling should be supported and promoted as it brings enormous environmental, health, economic, and social benefits to society”.

The 2020 Olympic Games have given cycling advocates in Japan a unique opportunity to have cycling discussed at the highest levels of government. We just have to hope that those in positions of power will see beyond the Olympics and build the kind of infrastructure a city like Tokyo deserves.

Jean Derome

Leave a Reply