Rice dominates the landscape in the archipelago whatever the season.

At the heart of Japanese culture, today this cereal is threatened by changing eating habits.

Rice and Japan are inseparable. Rice is such an integral part of Japanese life that it pops up everywhere. Indeed, some of the food foreign visitors always rave about is made with rice: from sushi to onigiri (rice balls) sold at convenience stores and specialist shops, and then, of course, the ubiquitous obento (boxed lunches), which come in endless varieties and can be bought in supermarkets, department stores and even railway stations.

But rice is not only food: it is at the heart of Japanese life and culture. Collaboration and sharing, for example, are very important values in Japanese society, and the origin of this can be found in the way rice is produced at a communal level. During the course of history, rivers have been dammed, their flow changed to slow it down, and ponds and irrigation canals were constructed to water the rice fields. A system created by valuing water is the reason why water entrances and exits exist in the rice fields, and many rice fields are connected so that the water flows from one to another in sequence.

This attitude of sharing is also stressed during the local festivals that are held first in the summer, when people pray for a plentiful harvest, and then in the autumn, this time to thank the gods.

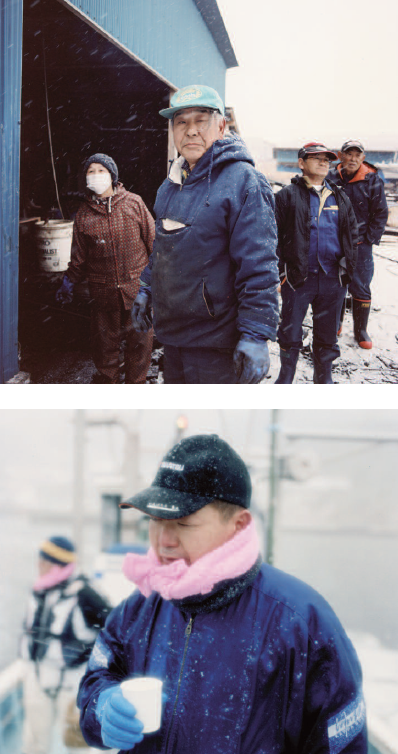

Rice is also a central feature in the Japanese landscape. You only have to leave the big cities to encounter seemingly endless stretches of the countryside and even suburban areas full of neatly cut paddy fields whose changes in appearance and colour remind us of the changing seasons. In spring, after planting the rice, the surface of the water shines like a mirror; in summer, the beautiful rice ears grow quickly in the strong sun, sea of green undulating in the breeze which then turns golden in autumn just before harvest; and everything goes quiet in winter, when the rice fields endure the harsh cold while the soil quietly recuperates.

Rice cultivation became popular in Japan because this country’s hot and humid climate was ideal for growing rice, and the water, which contains plenty of underground minerals, is a nutrient, making it possible to grow rice in the same fields year after year.

Improvements in cultivation techniques over the centuries has allowed rice to flourish.

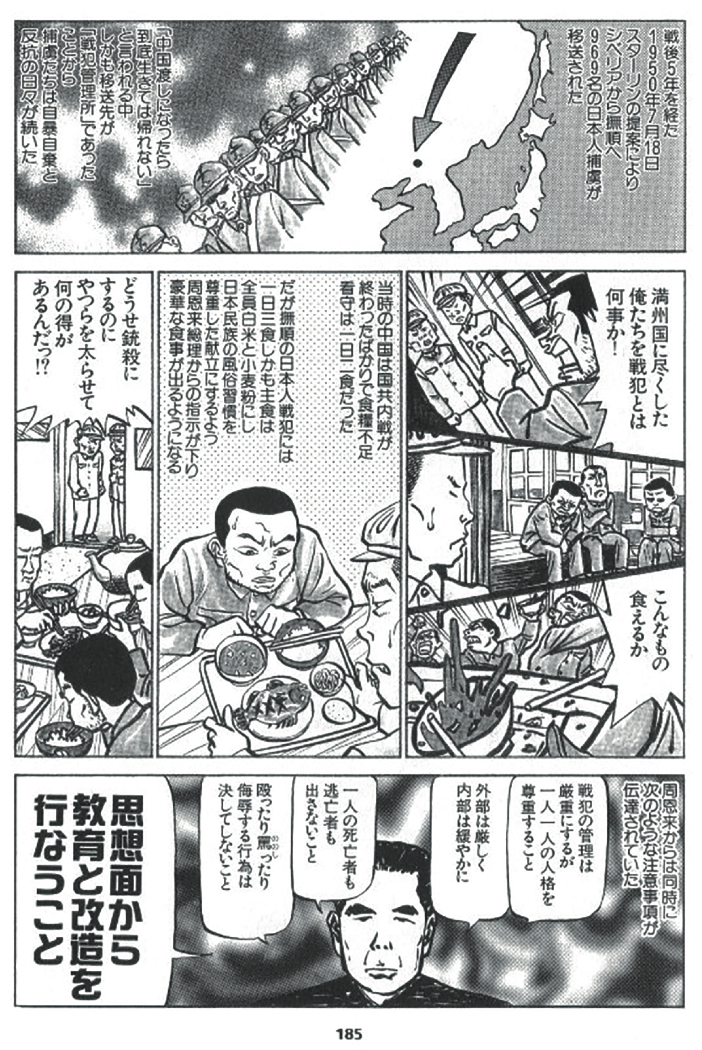

Since rice cultivation was introduced from China as long as 3,000 years ago, it has become Japan’s staple food, supporting the lives of millions of people. The technology of its cultivation rapidly spread eastward through the Japanese archipelago. Since similar pottery culture is seen from Kitakyushu to the Tokai region, it is estimated that technology spread rapidly in about 200 to 300 years. In this respect, the Yayoi period is thought to have been a turning point as rice replaced nuts as the country’s staple food. The spread of rice culture also increased the number of people that could be fed, at the same time improving the nutritional content of their diet and their health.

What’s more, rice yields more than any other cultivated plant, so those who controlled the paddy fields were able to gain wealth and power very quickly. As a result, from around the Kofun period (from the 3rd to the 7th century), there was a gradual transition from a regional nation to a centralised nation, and the gap between aristocrats and the common people widened accordingly. At that time, rice was used to pay the tax on the rice fields.

In the Nara period (710-794), white rice began to appear on Japanese tables. However, it was reserved for the aristocratic elite. Common people, on the other hand, ate low-polished glutinous rice called “black rice”. Sometimes it was mixed with millet.

From the Kamakura period (1185-1333) to the Muromachi period (1336-1573), productivity increased due to the introduction of new techniques such as double cropping and the use of cows and horses, the development of irrigation facilities using water wheels, and the development of fertilisers.

In the middle of the Edo period (1603-1868), cooking pots with heavy lids, which had never been seen before, became widespread, and the way to cook delicious rice became established. The amount of water needed to be adjusted depending on whether old or new rice was being cooked, and the cooking was not completed until the rice absorbed all the water. It is said that it was around this time that people began to debate how to cook rice.

Around the same time, the habit of eating three meals a day became established, together with the development of a modern diet. Also, from the latter half of the Edo period, rice varieties began to be improved.

The Meiji government changed tax collection from rice to a money-based system, and from 1868, large-scale cattle breeding started in order to increase the productivity of agricultural products.

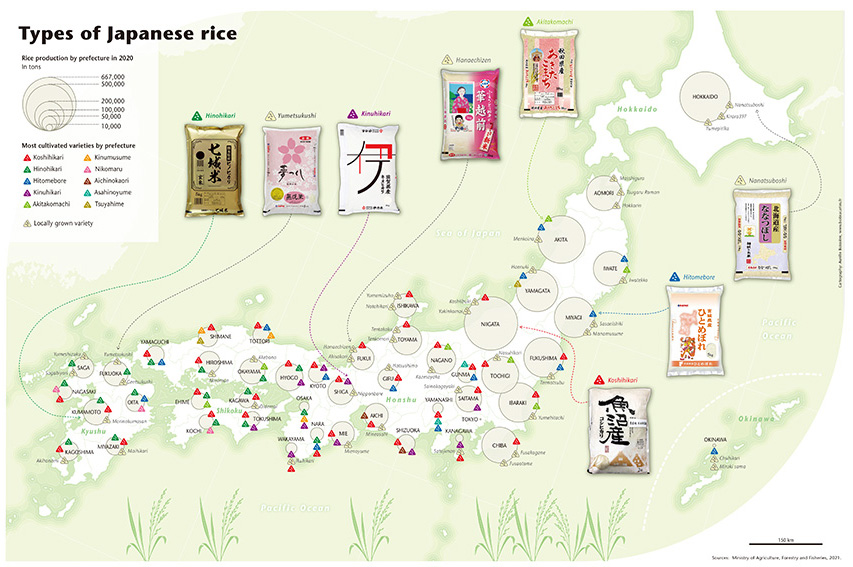

Currently, Koshihikari is the most widely available rice in Japan. It was developed in 1956 and quickly established itself as a top variety because of its excellent quality and taste and its resistance to the most serious disease at that time, “rice blight”. Production has progressed in various places around the country, and since 1979 it has been the number one planted variety in Japan. Since then, rice varieties have improved steadily, and as of 2019, there were 800 registered varieties, of which 271 were grown for staple food. Unfortunately, there is also a dark side to this story: the farmers who work the paddy fields are growing old and dwindling in number. Abandoned, overgrown plots are a common sight. Because of how small their farms are and how low rice prices have fallen, many farmers find it impossible to make ends meet. Indeed, according to certain commentators, Japanese agriculture has no money, no youth, and no future. In 1960, for example, the average annual consumption was 118.3 kg per person. Now, on the other hand, it’s only 53.5 kg, i.e. about half the rice they used to eat 60 years ago.

Throughout the postwar years, the government has taken upon itself to protect farmers’ interests, and things have not changed, particularly when it comes to the threat of rice imports. Even in the 2019 trade deal with the United States, tariffs and quotas on U.S. rice imported to Japan set in the early 1990s remained in place, reversing the provisions of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, according to which Japan would have accepted 70,000 metric tons of American rice per year tariff-free.

So what’s the future of rice farming in Japan? According to a 2018 government paper, premium brand rice, which sells for relatively high prices on the market and can boost the income of farmers, is receiving plenty of promotional support from local governments. While competition among regions growing brand-name rice intensifies, rice used for feed – which is subsidised by the national government – is fast becoming a popular crop with farmers as well. The National Agriculture and Food Research Organisation is now focusing its efforts on creating safe and reliable domestic rice varieties that produce high yields, have a good flavour, and are easy to cultivate, matching supply and demand between producers and businesses.

Gianni Simone

MAP Types of Japanese rice