According to gerontology specialist Akiyama Hiroko, Japan should be a pioneer in the management of aging.

As Japan and the rest of the world’s population is getting older, we need to reconsider the role of elderly people in our society. Regarding this urgent issue, Zoom Japan talked to Akiyama Hiroko, Professor Emeritus at the University of Tokyo and a member of The Institute of Gerontology (IOG). Akiyama is an expert in gero ntology who has spent 30 years in the United States, where she obtained a PhD in Psychology from the University of Illinois.

How did you get interested in gerontology?

Akiyama Hiroko: Actually, I originally specialised in social psychology. Gerontology is an interdisciplinary field as it has links with medicine, economics, psychology and sociology. That’s why each expert’s background is different. It is not possible to approach and solve social issues through just one academic discipline, so this is a system where everyone works together. The Institute of Gerontology (IOG) includes researchers from all the ten faculties at the University of Tokyo, including medicine, economics, etc. Anyway, to answer your question, I have been studying issues related to an aging society from the citizens’ point of view. It is a new field full of possibilities because we are approaching a society where people will live for 100 years. In this respect, Japan is the ideal place because it is among the fastest aging countries in the world and the percentage of elderly people is already about 30% of the total population.

It seems that aging-related research in Japan is mainly geared toward geriatrics (prevention and treatment of elderly people’s diseases and disabilities), while there are few opportunities to study gerontology. Why is that?

A. H.: The reason why Japan is lagging behind in the comprehensive study of the problems of the elderly is that, traditionally, the family has been expected to take care of them. In the past, multi-generational families (older people living with their children and grandchildren) were common in Japan. The government entrusted the younger generations with the care of the elderly and didn’t get involved. However, as you know, the family structure has changed rapidly, and the number of households where the elderly live alone have increased significantly. After all, we are living longer, and children can no longer shoulder the responsibility of looking after their parents all by themselves. Even the current public welfare system can no longer cope with the situation. Therefore, we have to come up with different policies; a new system that reflects the changing times.

Indeed, it is quite hard for people in their 60s to look after their parents. We sometimes hear of middle-aged people who have killed their parents because they couldn’t bear the physical and mental stress.

A. H.: The so-called baby boomers are now around 75 years old, and their opinions on getting old are quite different from that of their parents. For one thing, many of them don’t expect to be taken care of by their children. That is especially true in urban areas. It could be different in the countryside, but an increasing number of people in Japan don’t want to be a burden on their children and are aiming to be independent and live in good health.

Even now, there’s a prevailing idea that old people are no longer useful.

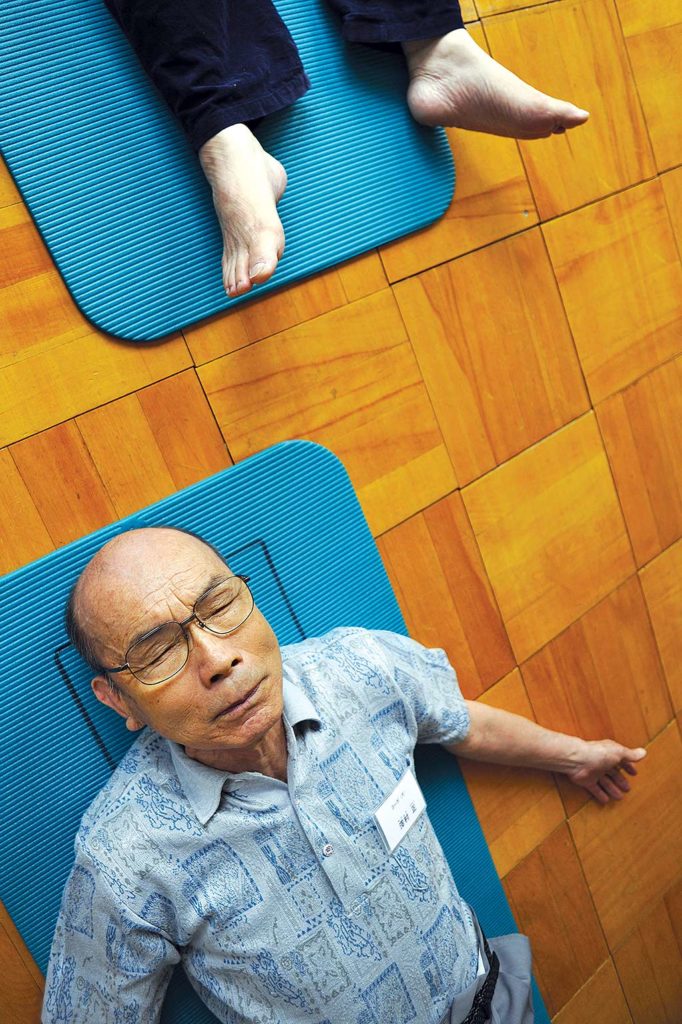

A. H.: That’s a very common misconception. Think about it. Now more and more people live to the age of 100. How can you say they are old when they reach retirement age? How can you say their life is over at 60? In any case, you only have to look at the statistics to see that elderly people’s level of health today is completely different from a generation ago. For example, they walk faster, their hand grip is stronger, and they are generally healthier. Not only that, but they are also more active. Many people in their 60s and 70s, for example, decide to further their education. In other words, they want to be active as much as possible. This, I believe, is particularly true in Japan.

Now we often talk about a Second Life starting after retirement. I’ve been to Italy and France and talked about it with the locals, and their usual reaction is, who wants to work? (laughs) As you know, Italians are happy if they can retire earlier than the normal retirement age. They want to get rid of their job as soon as possible, and once they become pensioners they just want to enjoy their life. To them, it is like a long vacation. That’s not always the case in Japan. Many people in their late-60s and 70s decide to keep working, but in a different, more flexible way, maybe only twice a week. They look for a job where they can decide when and how much they are going to work, that’s the important thing. And they don’t do it only for economic reasons (e.g. having a small pension). Many want to keep playing a role and be connected with society. This being the situation, we’re aiming to create an environment where the elderly can work as long as they want to. Of course, we’re living in an age when the Japanese population is shrinking and the number of young workers is declining. In this sense, I think older people can be an important human resource.

For some years, everybody has been talking about “the aging society”. However, some people now prefer to call it choju society, which is a society with “a long and healthy life span”. I guess you agree with them?

A. H.: Of course. There was a time when people in Japan aspired to the same kind of life. The trajectory of men’s lives (at least for those who lived in cities) consisted of getting a job as soon as they finished university and working for the same company until they reached retirement age. Women might work after graduating, but would leave their job upon getting married and having a child. This was considered the proper, decent way. However, many things have changed in the last 30 years or so. We live longer and can plan our lives differently. Now, for example, you can have two careers instead of one, and you can change it at any time. Recently, it has even become possible to have another job on the side. It is a very different lifestyle from that of our grandparents. I think this is a very positive change.

Now, I don’t mean to say that life is getting easier. Of course, there are various problems left to solve. More old people, for example, may be physically healthy but suffer from dementia. At the same time, though, I think we’ve reached a new degree of freedom as there are new possibilities that never existed before.

This is good news for the economy as well. More people living longer means new challenges, but also new opportunities for innovation. There’s a new expanding market; it is a veritable gold mine. Therefore, many companies can be proactive in solving the problems related to old age. It could be housing or transport or food, the possibilities are endless. If done well, we can create a new economy, and Japan is a front runner in this respect because we are already in this kind of situation. However, all countries’ populations are aging too. Even in Africa, life expectancy is increasing. Until now, African countries had high child mortality, but chronic diseases have become the number-one cause of death today. That’s a sure sign that people in Africa are aging too.

However, though other countries are starting to have the same problems, they are five, ten, or twenty years behind Japan. Of course, they can follow our example. Japan, on the contrary, has no model to follow. We are the trailblazers and have to find the solutions. That means that we can then sell those innovations abroad. It is a huge global market that’s just waiting to be exploited. Let’s consider Asia. China’s population is aging rapidly; it is the same for India. Think about the world’s two biggest populations getting old. It is an extraordinary number of elderly people. Japanese companies should aim to penetrate this huge market – it is an opportunity not to be missed.

What should be done to change people’s opinions about aging?

A. H.: I’m aware that there are both many challenges as well as new possibilities. Therefore, it is better to focus on thinking positively and considering all the things that people in their 70s and 80s can do in the future. As I mentioned earlier, old people were used to being taken care of by their children. But now they want to be independent. They want to continue to make their own decisions instead of always deferring to their children.

The IOG launched the Kamakura Living Lab [Kamakura is a city south of Tokyo], a platform for open innovation. Many companies are coming up with and testing new ideas. One of them is a monitoring service. It is mainly geared towards the children, not their elderly parents. Manufacturers have developed various new technologies for adult children to remotely monitor their parents by placing sensors in the house so that they can check on their parents’ safety and health. That could be very reassuring for children who are unable keep an eye on their parents all the time. The problem is, old people don’t like it. They don’t want to be watched by their children. It is just annoying. They want to play a more active role and not be treated like children. For example, they want to be able to make up their own minds about whether it is the right time to take a bath, not just letting their children know when they fall down or feel sick in the bathtub. In this sense, a wearable sensor can tell you, among other things, what your heart rate and blood pressure are, and if your blood pressure is high, you know you should wait until tomorrow morning to take a bath. That’s a much better option for old people. It gives them the chance to monitor themselves and be in charge. In short, manufacturers must understand the real needs of elderly people. They should focus on those issues, not the needs of the children. Obviously, children worry about their parents and their own responsibilities; they want to be reassured their parents are alive and well. But that’s not the point; we can live a relatively normal life even when our body becomes weaker. These things should be done in a way that does not harm the parents’ sense of self-respect. So let’s focus on what they’re having trouble with, and what kind of life they want to live.

You’ve met and talked to many elderly people during your research. What are their most common complaints?

A. H.: They don’t like to be categorised as inherently weak and vulnerable. They think they can carry on living as before provided they get the right tools and a little support. After all, there are people in their 70s and 80s who are still quite healthy and active, so age is not necessarily a factor. Also, in the old days, there were not many options for old people in terms of where they could live, so most of them ended up living either with their children or in a long-term care facility. But now they have more choices. Yet another issue is the choice of when and how their life should come to an end, as depicted in the film Plan 75. I think more and more people want to decide for themselves how to set off on their last journey. Now, for example, if you have cancer there are various treatments available, but some people may not want to endure long and painful treatment and may choose to die sooner rather than later.

At the IOG you are not only engaging in lab research but are involved in a social experiment, also known as action research. It seems that you are particularly active in Chiba and Fukui Prefectures.

A. H.: We have been surveying 6,000 elderly people every three years since 1987. The main purpose is to identify issues we need to address in a rapidly aging society. However, when I returned to Japan about 25 years ago, I felt that what we need to do now is to search for solutions and take action. That’s how this new project got underway. The purpose of our research is community development in an age of increasing long life. Rebuilding the social infrastructure of ordinary cities in both urban and rural areas entails much more than just providing housing, roads or transport. We have to prepare an adequate medical and long-term care system. Also, we have to create more opportunities for lifelong learning and employment for the working elderly. Our ultimate goal is to rebuild the cities for a society where people are going to live for 100 years. As you can imagine, this requires a lot of work because the current structure of society was created when life expectancy was only 50 years or so.

Kashiwa, in Chiba, is a typical commuter town. We’ve created a research team together with the residents and government officials to look into the problems old people face now, such as transport and medical care. That’s why our team includes a professor of mechanical engineering and a law professor among other people. Companies such as Toyota, Nissan, Mazda, etc., are also involved. This way, we’ll be able to develop new means of transport. As for medical care, it shouldn’t be centred only around hospitals as it has been until now, but should be organised instead on a community-based, comprehensive care system. In other words, we want to create a model where you can receive medical and long-term care wherever you live without having to worry. There are many overlapping issues between metropolitan areas and more rural regions like Fukui, but each place is unique in some respects, and we need to address those differences as well.

How about you? Do you have any personal wishes for Japanese society of the future?

A. H.: I hope it will become a place where people can keep active well into their old age. In Japan, as in many other countries, there’s still a lot of agism. The Japanese calendar includes a day when we honour the elderly, but to truly respect someone means more than that. We (I include myself in this category) don’t want to be put on a pedestal and honoured like someone who’s already dead. We think that we can still contribute to society as we grow older, even if our contribution is small. People should be judged as individuals, not simply as members of a certain age group. After all, some people are really weak even at 60, while others are full of energy at 80.

In the past, we’ve focused on extending our life expectancy. Then, in the 1980s, the average life expectancy within developed countries reached about 80 years old. However, we saw many older people living in poor health, even bedridden. Now, we’re working on extending “healthy life expectancy”, which we define as the average number of years that a person can expect to live in “full health” (i.e. excluding the years lived in less than full health due to disease and/or injury). This, of course, is good for individuals and society as a whole. Healthy life expectancy is an important goal right now, but for me it is also essential that each person keeps engaged and connected to society, perhaps taking on a new role. Extending “engaged life expectancy” is our next goal. In this respect, the structure of the cities must be changed in such a way that it makes it possible for the elderly to go out and play an active role, and the social system must be reorganised so that old people can pursue new goals, including opportunities for further education.

Interview by Gianni Simone