The folklorist Ueno makoto was born in 1960. he is an expert on the man’yôshû, the first anthology of Japanese poetry that dates back to the year 760. he focuses on the founding texts of Japanese culture, including the Kojiki. he currently teaches in the literature department at Nara University.

The folklorist Ueno makoto was born in 1960. he is an expert on the man’yôshû, the first anthology of Japanese poetry that dates back to the year 760. he focuses on the founding texts of Japanese culture, including the Kojiki. he currently teaches in the literature department at Nara University.

Could you describe how you were introduced to the Kojiki? And does it have anything to do with your becoming an expert in this foundational text of Japanese culture?

Ueno makoto : I was born and grew up in Fukuoka on Kyûshû island. There are many sanctuaries dedicated to the empress Jingu in that region. So ever since I was a child, without even meaning to, I learned many stories about her that are drawn from the Kojiki. In Japan, people maintain a special relationship with the temples and sanctuaries in its regions. That is also the case with both the universe of the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki (The Chronicles of Japan). That is how I was introduced to the stories that are told in those books. But that’s not what drove me to start analyzing them.

What is the best way of defining the Kojiki, according to you?

U. m. : Literally, the Kojiki is the book of “ancient facts”. It’s a document in which the eighth-century Japanese compiled their ancestors’ stories. That is why they are “ancient matters”.

The Kojiki is mainly a compilation of Japanese myths. If we compare them to other myths, particularly the Greek ones, what are the main differences, if indeed there are any?

U. m. : As Levi-Strauss said, myths are a form of wisdom. I think wisdom is something that all human beings share. In fact, when you compare myths from one country to another, many similarities can be found. In a certain way, Japanese myths do resemble the Greek myths.

What does the Kojiki mean to the Japanese today?

U. m. : The year 710 is when Heijô-kyô [Nara’s former name] became the capital. And I believe that the appearance of the Kojiki two years later may have something to do with this change. In other words establishing a new capital, and the advent of a new era, favoured the emergence of nostalgia for the past. France is a country that is renowned for its scientific and technical expertise. Its agriculture is also one of its main assets. Nevertheless, for me, France is the Opera, the Louvre, or the Orsay museum. It is a country in which history, art and culture all converge. And that is what gives it all its charm. I’d like to say that in some way the Kojiki presents a concentration of history, art and culture for the Japanese.

Nature plays a major role in the Kojiki. When reading it 1300 years later, what lessons can Japan learn from it today?

U. m. : In Japan, mountains are believed to shelter gods, and rivers have their own divinities. When human beings die they, too, become ancestors that are worshiped. For the Japanese, gods are part of nature. It’s different for monotheist religions. In a universe in which there isn’t a unique god, things aren’t settled by rules that are set in stone, they adapt according to the fluctuation of relationships between people. In Japan, it is believed that things aren’t settled during meetings, they also depend on the nature of our relations towards and with others. That is why it sometimes takes time to establish what the nature of the relationship is. If you read the Kojiki, you’ll see that in important situations, the gods take a decision at the end of the meeting. For the Japanese, there is no one universal god; there is a multitude of them amongst which there are the good ones, the bad ones, the beautiful and the ugly. I feel that by using simple words to describe the way the Japanese think, it makes it easier to share their culture with the rest of the world.

Interview by G. B.

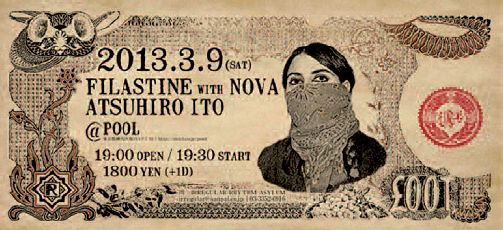

Photo: Ueno Makoto