Perception of tattoos in Japan is paradoxical. The archipelago has inherited a long tradition that fascinated the first western visitors and strongly influenced foreign tattoo artists, but tattooing is also subject to strong prejudices and those bearing tattoos are often ostracized. They are banned from public baths, saunas, swimming pools, sports clubs, thermal hot springs (onsen) and even some beaches. In preparation for the 2020 Olympic Games the Japanese tourist agency has encouraged these establishments to lift the bans in order to prevent any incidents with tattooed athletes, but apparently this tolerance will only apply to foreigners: Japanese people with tattoos will still not be allowed to enter. Over the past twenty years tattoos have grown in popularity in Japan, under the influence of American culture and early 2000 J-pop stars such as Amuro Namie and Hamasaki Ayumi. Tattooists used to have to be discrete about their art, but tattoo parlours have now appeared in trendy neighbourhoods such as Harajuku and Koenji in Tokyo. In the late 80s there were only 250 parlours across the archipelago, but there are ten times as many now, and several specialist magazines covering the topic are now being published.

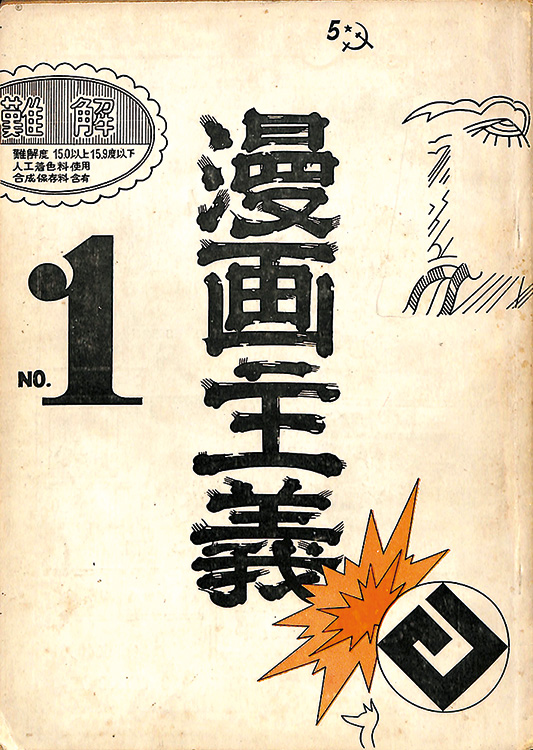

In Europe and the United States an estimated 10% of the population are said to have tattoos, but the number in Japan remains small. Most people have little tattoos (one-point tattoos), which have very little to do with the tradition of “brocade skins” (nishiki hada), the colourful tattoos that cover the whole body, and have been largely associated with criminals (yakuza) as depicted in films and the media in the 60s and 70s.

Not all yakuza have tattoos, just as everybody with a tattoo is not a criminal; this is just as true today as it was in the past. The exhibition Tatouages et Tatoues (Tattoos and Tattooed) at the Quai Branly Museum of Primitive Arts in Paris incorrectly highlighted the underworld connections aspect, says anthropologist Yamamoto Yoshimi in his book Irezumi to Nihonjin (Heibonsha, 2016, only available in Japanese). However, this cliche isn’t only prevalent abroad and 45% of Japanese people also believe that tattoos are associated with criminals, according to a survey by the Kanto Bar Association (Tokyo region). For most Japanese people tattoos are specifically connected to the underworld.

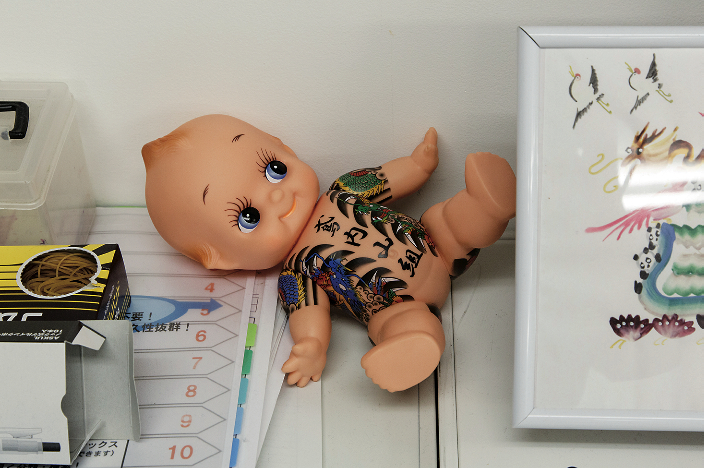

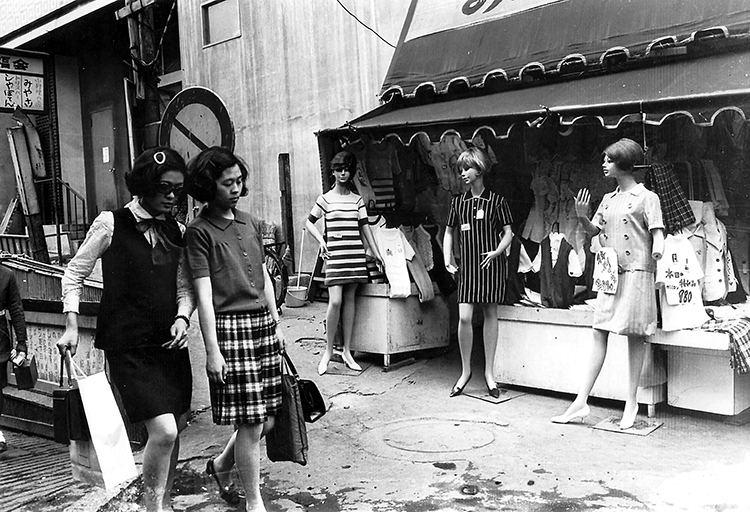

Tattooists, traditional ones included, have noted that their clientele is changing. Until the 80s people getting tattoos were associated with certain social groups: craftsmen, salesmen, artists, bar hostesses, criminals, etc. Nowadays they come from more varied backgrounds, and the number of women is increasing, though the phenomenal growth experienced in the early 2000s is starting to drop. The wabori (Japanese tattoo) style of “engraved” body is still confined to a small minority of people who are proud of being part of this age-old tradition. However, this heritage isn’t what attracts young Japanese women, who often prefer more discrete patterns. Tattoos are part of their everyday life, like dyeing their hair, piercings or colourful nail polish. Contemporary tattoos take inspiration from traditional iconography as well as from manga and anime. Nowadays many of those getting tattoos, as well as the tattoo artists themselves, have no idea of their symbolic meanings. “Traditional tattooing is not just a technique”, says Horiyoshi III (see page 4), one of the most famous contemporary tattooists and a disciple of Horiyoshi I (Muramatsu Yoshitsugu), a legendary figure of tattoo art. “Tattoo motifs are linked to stories, mythical figures, legends. You need to know their significance, study the ukiyo-e. Without this knowledge, which is revealed in the details, the result will always be unsatisfactory”.

The first tattoo artists were wood carvers working for famous ukiyo-e painters, sourcing their themes from the rich body of polychrome etchings and reproducing the work of Kuniyoshi, Yoshitoshi and others. Pictorial tattoos were called horimono (carved things). Irezumi (to inject ink), the style more common nowadays, appeared later. The tattooists sought inspiration in traditional imaginary: mythical figures, dragons and carp denoting strength, or flowers with symbolic meanings. Tattooists were closely connected to the world of etching in terms of both their technique and iconography.

Women weren’t the last to embrace the fashion for tattoos. In red light districts lovers would get a dot inked on the back of their hands as a sign of their love for each other. This practice was called irebokuro (to insert a beauty spot), and when their hands touched the dots would cover one another. These love tattoos were described by Fujimoto Kizan in his anthology on love, the Shikido-okagami (Great Mirror Of Love), published in 1678. Finally came the mind-boggling fashion of having one’s body completely covered with breathtaking tattoos. It reached its peak during the first part of the 19th century, a decadent time for the Shogunate, marked by the peasants’ revolt (ikki) and libertarian movements that saw crowds pillage and ransack everything in their path while shouting “eijanaika” (“We don’t care!”). In this way, “Man honoured the noble virtue of frivolity”, Tanizaki Junichiro wrote in his essay on tattoos (1910), “and bodies were covered with entangled lines and undulating colours”.

The first foreigners to travel to Japan were fascinated with these “brocade skins”. Fearing that these ukiyo-e on the skin would be perceived as sign of barbarism by westerners, the Meiji oligarchs banned tattoos in 1872. Tattooists continued to practise their art in secrecy, particularly in port cities (Yokohama, Kobe, Nagasaki), with sailors and celebrities as their clientele: Pierre Loti, Tsar Nicolas II, Prince George (later King George V), Francois- Ferdinand of Hapsburg-Este, the Archduke of Austria, Queen Olga of Greece and many more.

It was only in 1948, under the American occupation, that tattoos became legal again. They flourished among manual workers, miners and the yakuza – who turned getting a tattoo into a kind of rite of passage. This is not the case today, when fewer and fewer criminals are getting tattoos. Tattooing began to change from the 80s onwards as the bamboo stylus equipped with needles, used for handmade tattoos (tebori), was replaced by the electric tattoo machine, which has made tracing lines easier, faster and cheaper. Japanese tattoo artists recognize that their American peers have talent, but consider that their “skin etchings” generally lack balance.

By becoming fashionable Japanese tattoos have lost another of their characteristics: the wabori was supposed to be a hidden beauty, seen only on certain occasions (neighbourhood festivals, for example), and not always on display. In spite of being part of centuries-old popular culture, traditional tattoos, just like erotic etchings, have limited social acceptance due to a kind of Victorian prudishness, however admired they have become abroad as expressions of artistic refinement

PHILIPPE PONS

Philippe Pons used to be a correspondent in Tokyo for the french daily newspaper Le Monde, for which he still writes. He is the author of several books on Japan and Japanese society, including Peau de brocart: le corps tatoué au Japon. Published in 2000 by seuil, unfortunately, it has sold out and copies are hard to find.

Leave a Reply