As one of the oldest breweries in the archipelago, it endeavours to preserve traditional methods of production.

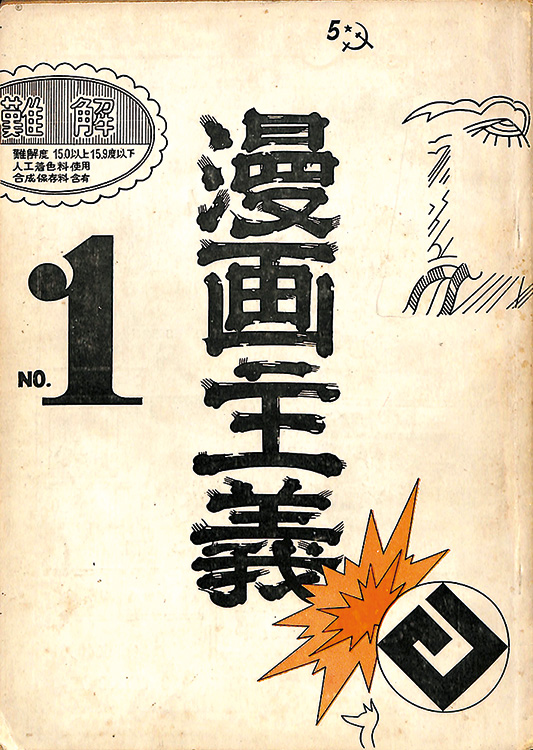

The celebrated logo of the Kenbishi brewery, founded in 1505.

Kenbishi is more than just the name of a sake brewery. Founded in 1505, it’s historically one of the oldest and best known in Japan. Barrels displaying its brand name are often seen in depictions of Edo, in prints by Utamaro, Hiroshige or Kuniyoshi, and the name Kenbishi has also appeared in kabuki theatre plays. History relates that the celebrated 47 samurai drank Kenbishi before setting out to avenge the death of their daimyo (feudal lord), Asano Naganori, unjustly condemned to commit ritual suicide. Though situated in Kobe in the west of the country, the brand was a favourite of the inhabitants of Edo, to the point that it almost became a synonym for “sake”, and is part of the culinary history of the period. The brewery also possesses major archives, and continues to collect material about the history of Kenbishi.

Ever since it began, the brewery has kept its original logo (it was the first to invent the idea of a “logo”) and still offers just five different blends, which has little to do with its capacity to produce 3,500,000 magnum bottles (1.8 litres) a year. It is renowned for not producing novelty or other types of sake: and it sticks to this principle. Kenbishi is quite unique in the sense that it’s a large scale brewery that produces sake at affordable prices without resorting to industrial methods, but instead uses the traditional Yamahai method, by which fermentation takes place naturally thanks to locally occurring yeasts and “lactobacilli” present in the surrounding air, which takes a great deal of time.

But, at a time when the world of sake is enjoying increased interest from abroad, and with the appearance of new kinds of sake created by the current generation of producers, does this brewery have a new vision for a “21st century sake” after more than 500 years of history? Doesn’t it suffer from a rather old-fashioned image of a “sake of a former generation”?

“No!” the present owner of the brand, Shirakashi Masataka, replies succinctly with a calm smile. “The slogan that we’ve observed for generations is “we must be like a clock that’s stopped”. Taste changes with passing time. If you chase after what’s fashionable, you become like a clock that’s always slow and never shows the right time. On the other hand, a clock that’s stopped shows the right time twice a day without fail.” The taste of Kenibishi is very distinctive. It could be the model for sakes from the Nada district of Kobe, which are known as “masculine sakes” due to the high mineral content of the region’s water. All the blends, each slightly different, share a taste that’s rich in umami, both complex and powerful, but never too dense thanks to its metallic quality. It’s a taste that, once tried, is never forgotten, which can be recognised even in a blind tasting. It’s not a taste that pleases everyone, but it has many faithful fans, both young and old.

“It’s a taste we want to perpetuate. And our production is entirely geared to always being able to supply our clients with the same sake. We don’t use traditional methods just for the sake of it, but we make every effort to use traditional means to ensure the preservation of the Kenbishi taste,” maintains Shirakashi Masataka. In fact, visiting this brewery has been a unique experience. It formerly had eight cellars, but seven were destroyed during the Great Hanshin/ Kobe Earthquake in 1995, in which four employees lost their lives. Since then, Kenbishi has rebuilt three cellars in the same location, and in these four cellars, a total of four toji (master brewers) and a hundred employees work during the sake production season from October to April.

From outside, these enormous recently-built concrete buildings are rather intimidating, and resemble a factory. But inside, we can see large and small wooden barrels, and can smell kakishibu (fermented juice of unripe persimmons), traditionally used as coating to seal and preserve wood. At the time of our visit, it was out of season, and they were taking the opportunity to repair and maintain the production equipment. On the terrace, fish were drying in a basket. “Members of staff who have lunch here prepare the food themselves,” explains Shirakashi Masataka. It was as if a traditional workshop was enclosed inside this large modern box. Whereas in a similar sized brewery, usually only around forty people are needed on average, Kenbishi employs double that number. “Our brewery is quite large, however it’s not machines that do the work, but our skilled workforce, which allows us to employ traditional methods.”

In addition, all the materials used have been carefully selected. For instance, they prefer to continue using wooden barrels to steam the rice because the results are better in comparison to metal barrels. On the other hand, the barrels to store the sake are made of metal, as they reckoned that there was a higher risk of hygiene problems with wood, and they did not improve the taste. However, wooden barrels are still used in order to help control the temperature during the fermentation of the shubo, (the starter), as the temperature change is gradual, in contrast to metal, when it can be rapid. In the koji room where the koji fungus is prepared, an essential stage in the fermentation process of sake, steam cooked rice is spread on small trays, so that they can be removed easily as soon as the spores develop. It’s an age-old process, and no electric heating is used to control the temperature in this room. “In general, other producers only use these small sized trays for special brews as they necessitate a lot of care. But now we’ve decided to take on people so that we are able take this kind of care to produce all our sake, across the board,” Shirakashi Masataka assures us.

Nor do they produce namazake (unpasteurised sake), which has lately become very popular due to its fresh taste. “Namazake is good, and I’m not against this method. But if everyone starts to produce sake that can be drunk immediately, we’ll lose the ability to imagine a sake whose flavour improves by waiting a year or two. Of course, you lose this fresh flavour with pasteurisation, but on the other hand the umami taste increases. Our sake is made so that its taste improves with time. Normally, we keep it for two or three years before bottling it, after mixing it with some older vintages to add complexity to its flavour. We even have a thirty-five year old vintage; we taste it every year to check it and decide when it would be best to market it, but every year we think that there’s still room for it to develop,” observes the boss of Kenbishi. This long-term point of view also represents the same investment Kenbishi makes in the maintenance of its equipment, as it’s necessary to be certain that there’ll always be craftsmen to replace it. There’s only one person in Osaka who knows how to make large barrels. When Shirakashi Masataka learned he was going to close his workshop in 2020, he sent two of the brewery’s employees, who wanted to learn the secrets of barrel making, to be trained by him, and then built a workshop next to the cellar to make barrels so that they could continue to use them. To make small barrels, he officially employed the craftsman who produced them, and asked him to use his workshop to teach barrel making.

Now, this workshop not only provides tools and equipment for Kenbishi but aims to fulfil orders from other producers in the future. He has acquired a machine to make mats from rice straw to wrap around sake barrels to serve as temple offerings. Nowadays, throughout Japan, these straw mats have been replaced by those made of plastic. Shirakashi Masataka thought long and hard before obtaining this machine, as it doesn’t directly concern the taste of sake. “To give an offering to the gods of sake, the sake must be decorated with ears of rice, however, with plastic it becomes an offering to the petrol god. That complicates the lives of our gods, doesn’t it?” he adds jokingly.

This workshop making machines and tools brings to mind what Imada Miho (see pp. 8- 10), a female toji told us. She doesn’t conceal her admiration for these master brewers from a former generation who possessed a comprehensive knowledge of the world of sake: they knew how to cultivate rice (many of them were farmers) and how to weave the rice straw, as well as repair the barrels and the cellar roofs… Today, the world of sake is very specialised, but she explains that if, for example, it was necessary to make sake from nothing, these toji of yesteryear would have been able to do it. Contrary to what you might think, it’s only because they lack the time and the means that the small producers of hand-crafted sake are unable to undertake all these things. Regretfully, wooden equipment and straw matting must sometimes be abandoned. Only some of the larger breweries, those concerned about handing down the tradition, have the capacity to employ extra people so that this knowledge can be passed on. Kenbishi is a good example.

“It’s been suggested that I should buy forests in order to grow our own bamboo to hold the wooden barrels together… That would mean we’d be totally self-sufficient. But without going quite that far, I’d very much like to have somewhere to cultivate our own rice. As you’ve seen, we have to make our own equipment, otherwise we’d risk losing skilled workmen with the necessary know-how. It’s the same with rice: the farmers who are contracted to us are elderly. Rice for sake is more difficult to cultivate, and needs more care and manual labour. If the situation remains the same, soon there’ll be a shortage of rice suitable for sake. To create the means of cultivating our own rice is a way of guaranteeing both the quantity and quality of the rice. We obtained the appropriate licence to do this several years ago, so that we can prepare the land and ensure there’s work for those who come to work here for six months of the year. There’s no fixed retirement age for our workers, they can work for as long as they want and are able to. But if they were able to cultivate rice for the other six months of the year, it would be a way of guaranteeing them financial security, and our brewery would be, in that sense, self-sufficient… Just another dream…,” says Shirakashi Masataka with a knowing smile. But those who have seen all his previous efforts to make sure this know-how is not lost, know that it’s not just a dream, but rather a realistic and promising project that will come to fruition.

Naturally, after this visit, we are well aware of the real “meaning” behind the immutability of this timeless process. Of course, it’s a commercial product above all, but apart from this aspect, we can sense the feeling of responsibility, a “noblesse oblige” to preserve this sensory heritage. This is made possible thanks to the judicious and methodical archiving of material and old recipes dating back hundreds of years. Everything that’s done to safeguard this taste also contributes to the preservation of a tradition, the “culture” of sake as a whole.

In the period when sake was graded as “special”, “first class”, “second class” (the law was abolished in 1992), there was very little choice. It was unfashionable to taste and compare several different sakes at a time, rather a case of each to his own sake. As for my grandfather, he remained faithful to the brand with the double-lozenge logo. I can still picture him with a bottle of Kenbishi beside him at mealtimes. Of course, as I was still a child, I couldn’t join him in a drink, but when this sake is poured into a glass, I can smell a familiar aroma and recognise the taste I’ve known since the very first time I drank this sake a quarter of a century ago.

“That’s the reason we preserve this taste. It would be sad if you drank a Kenbishi and no longer recognised the taste your grandfather loved, wouldn’t it? You drink sake not just for the sake of drinking it, but to enjoy the way its taste has the power to bring back past memories. We believe in this power of sake,” maintains the owner of the brand.

“The metaphor of the stopped watch doesn’t mean we can sit back and do nothing. You need to imagine being at sea, always at the same spot, with the wind and the waves. The impression is that you always remain in the same place, but to achieve this, you need to move your arms and legs constantly, and observe the stars and the sky. We mustn’t skimp on the time and energy it takes to do it this way, or to stick to our principles and the conviction that we’re right,” he adds. To revel in this “real moment” together, our watch can also decide to be out of time with Kenbishi sake. At any rate, this brewery’s initiatives appear to be more relevant than ever, and the watch is bang on time!

SEKIGUCHI RYOKO