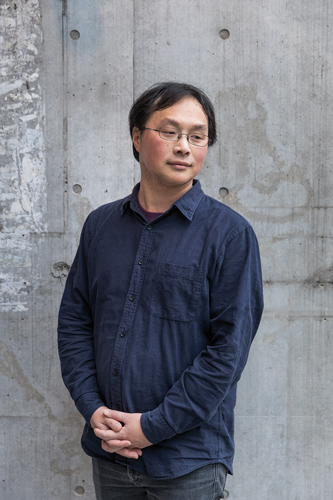

The rising star of Japanese cinema, Fukada Koji, takes a hard look at the family unit in the archipelago.

Fukada Koji’s Harmonium (original title: Fuchi ni tatsu, Standing on the Edge) was one of Japan’s best films last year, winning many accolades abroad. Fukada’s film is a tense, dark story that, for once, breaks the mould of traditional Japanese family drama.

What was the inspiration behind this story?

FUKaDaKoji :I first wrote a one-page synopsis in 2006 with the intention of exploring two distinct issues. The first one is the idea that senseless violence can happen to any of us. It could be anything – a murder, a natural disaster or an act of terrorism – but it always disrupts our lives. The second one is the concept of family. In particular, I wanted to challenge the naive and simplistic image of the Japanese family as portrayed all too often in TV dramas and in other media.

In 2010, you made the film Kantai (Hospitality), which seems to have many points in common with Harmonium. What’s the relationship between these two stories?

F. K. :Originally Kantai was supposed to be a pilot for Harmonium, and then it took on a life of its own. As you’ve noticed, the two films share the same setting (a machikoba), and the mysterious man who intrudes in the life of a lower-middleclass family, and proceeds to turn their quiet suburban life upside down. While working on the plot, I began to think that it would be interesting to include a few Marx Brothers-like gags, and in the end it became this sort of black-humour comedy.

Zoom Japan devoted its april issue to machikoba, so I’m curious to know why you decided to use such a place as the main setting for both of your films.

F. K. :Ten years ago, when I wrote the onepage synopsis that would eventually become Harmonium, I decided I wanted to use a small printer as the main setting for the film. I liked the image and noise of printing machines at work, which I had seen in many old films. But then I ended up using that setting for Kantai, so when I finally made Harmonium I switched to a metal workshop. I really like that kind of setting because it’s private and public at the same time. The father works downstairs, while the family’s living quarters are upstairs. Traditionally, this used to be a very common arrangement for many families in Japan. Also, it’s not just a matter of physical space. Because the private and public environments coexist, the family is morally and emotionally affected in many ways by what’s going on inside and outside the house. As a storyteller, I find this very interesting.

You have often declared your love for French cinema. When comparing Kantai and Harmonium, some reviewers have said the former reminds them of Eric Rohmer, while the latter is closer to Robert Bresson’s serious approach to film-making. Do you agree with their opinion?

F. K. :Different people often see different things in a film, and I’m not going to argue with that. I actually love both Rohmer and Bresson, so if my films remind people of these two great directors, I’m very happy. It’s even possible that I was unconsciously influenced by their style while working on my films. At the same time, though, I want to point out that I never set out to make a film which would be more acceptable to foreign audiences. It bothers me, for example, when someone says that my aim is to get my film screened at Cannes. My only purpose is to tell a story that, though set in Japan, deals with universal issues.

Why do you like Rohmer so much?

F. K. :I just love the way he tells his stories; his camera work and the dialogue. His films have a very contemporary feel. Rohmer’s characters are constantly talking about all sorts of things, but their words often hide their true feelings. It’s left to the viewers to sort out what they’re really trying to say.

What kind of family did you want to present in Harmonium?

F. K. :It’s a broken family; a nuclear family whose emotional ties – especially between husband and wife – have been broken for too long, until an unexpected tragedy makes them realise their situation. I

don’t know if they represent a typical Japanese family, but my parents were certainly like them. There was no dialogue between them, and eventually they divorced. Therefore, for me there is nothing special in the family I’ve portrayed in my film. When I was in Cannes, a few foreign journalists (probably from Europe) pointed out that Western family dramas usually focus on the husband-and-wife couple, while Japanese films seem to be more about the family as a whole. I guess it’s a cultural thing – not only in Japan but in East Asia as a whole – to preserve and foster traditional family values. It’s the same thing the Abe government is trying to do in this country.

The “romantic” relationship between husband and wife is never as important as their role as mother and father. This, unfortunately, all too often works to the detriment of their relationship.

What do you think about the Japanese government’s policy regarding the family?

F. K. :think it’s very inconsistent and full of contradictions. On the one hand Abe talks about fostering women’s role in society and the labour market through “womenomics,” but on the other hand it’s clear that for many members of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party a woman’s place is at home raising children. In Japan, it’s extremely hard to be both a mother and a career woman, and statistics show that many women prefer to keep working and be independent, even if this results in not having children or even not getting married at all.

How about the parent-child relationship in the film?

F. K. :In Japan we say, “Ko ha kasugai”, which means that children are a bond between husband and wife. Indeed, the daughter in this film is the glue that keeps the family together. Her parents have reached a point where they have nothing to say to each other. If it were just the two of them they would certainly be getting a divorce, but they decide to stay together just for the sake of their child. Again, this is a very typical situation in Japan, especially when the children are still very young. That’s why when the children leave home their parents suddenly realise they have become strangers to each other.

Judging from your film, one is left with the impression that you don’t think the family is a very warm place to be.

F. K. :You’re right. That’s exactly my main message, even more important than a meditation on violence. I believe each one of us is fundamentally alone in this world. Because living in this state of loneliness is extremely hard, we all look for some kind of support. This can be friendship, a family, or religion as I show in the film. Some people actually manage to forget about the sense of existential isolation that is part of the human condition, and are able to lead a happy life. However, there are moments when a particular event shatters the illusion, and you’re left facing your own isolation. We can be married, have children, etc., but

in the end we’re alone.

Your film was made on a small budget, and I heard that you didn’t spend a lot of time on rehearsals because of financial restrictions.

F. K. :Yes, this is definitely a small film, not only compared to films made in Europe, where directors usually have a lot more money to spend, but even compared to other Japanese productions.

So it’s still difficult to turn this kind of story into a film?

F. K. :It’s very difficult indeed. My film, for example, is an original story (i.e. it’s not based on a popular TV drama or manga) with an intricate plot. It’s not a romantic story or a light comedy, which

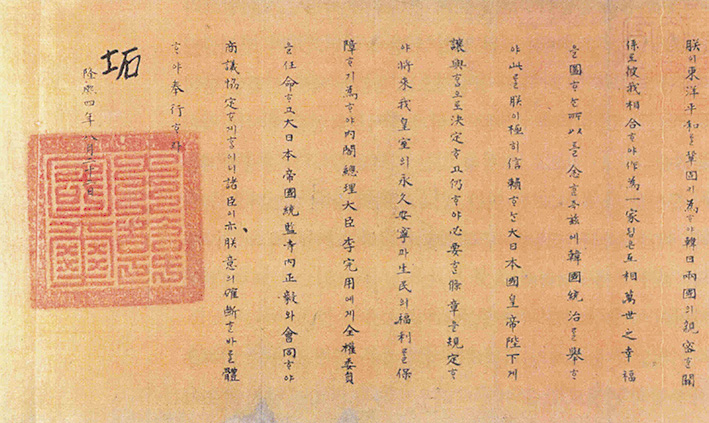

made finding financial backing even harder. I’ve made films for the last ten years, and the conditions in which I work have gradually improved because my films have been relatively successful, but, in general, I think that making films in Japan has actually become more difficult for a number of reasons. First of all, DVDs don’t sell anymore, and this badly affects our revenues. Also, major companies like Toho have a stranglehold on the domestic market, making it very hard for independent makers like me to survive. Usually it’s the state that should support small independent makers, but in Japan this is not happening. We don’t even have an organisation, like France’s CNC, to be responsible for negotiating subsidies and promoting smaller, non-commercial productions. In Japan, we only have the Agency for Cultural Affairs with a measly budget of 2 billion yen at its disposal. South Korea’s KOFIC, in comparison, has 40 billion, while the CNC has 80 billion. Our Cool Japan initiative has 20 billion yen on offer, but it must be shared among all kinds of cultural projects ranging from anime to crafts, even food.

The real problem is that in Japan, cinema is still regarded merely as an industry. As such, only what is guaranteed to sell (i.e. commercial blockbusters) gets financial support. We should change the whole system, but of course such a thing is very difficult to accomplish.

INTERVIEW BY J. D.

Leave a Reply