The sight of Mount Fuji always has a magical, even mystical quality.

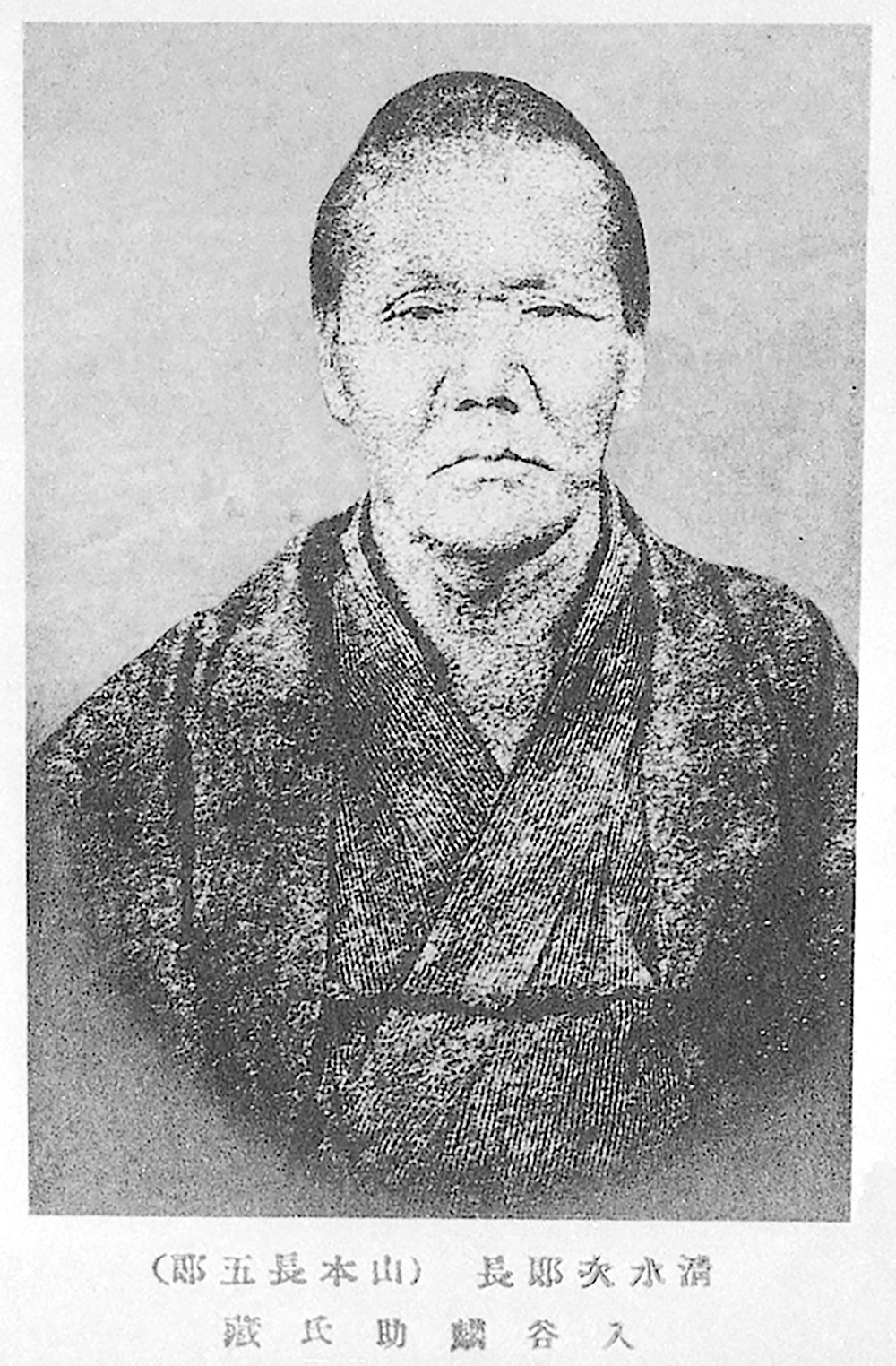

An extraordinary historical figure, the former yakuza promoted the opening up of the country.

After spending two nights in Shimoda, I took the first bus leaving for Toi, on the Izu peninsula’s west coast. From there, I crossed Suruga Bay by ferry to reach my next destination, Shimizu.

After spending two nights in Shimoda, I took the first bus leaving for Toi, on the Izu peninsula’s west coast. From there, I crossed Suruga Bay by ferry to reach my next destination, Shimizu.

I was still asleep when, around noon, our ferry made its triumphant entrance into Shimizu, Shizuoka City’s port district. Too bad, because it’s considered to be together with Kobe and Nagasaki – one of Japan’s three most beautiful ports. Shimizu’s ideal position in the middle of Japan’s east coast has historically made it an important strategic site and trading centre. Even the first Tokugawa shogun, Ieyasu, moved to this area when he retired, resulting in a naval garrison being stationed in Shimizu. The port was also opened to foreign trade in 1899, a move that coincided with the arrival of the steam engine and industrial modernisation.

Starting with the export of green tea, the port began handling products from Shizuoka and its neighbouring areas – first citrus fruits and canned goods, then Japan’s internationally famous motorcycles and musical instruments (both Suzuki and Yamaha are based in Shizuoka Prefecture).

The port responded swiftly to the start of the container era to become one of the leading exporters in the country and to play an important role in the era of high economic growth.

However, the scene that unfolded in front of my eyes when I disembarked was quite different. It might have been the time of day or the fierce sun beating down on the city, but I found a sleepy town almost bereft of people.

In recent years, the area has come up with plans to fight competition from other ports such as Yokohama and Nagoya, “create liveliness” and attract more tourists. Close to the waterfront, for instance, they have built S-Pulse Dream Plaza, your standard-fare commercial complex featuring the Shimizu Sushi Museum (the first in Japan!), a football shop (the Shimizu S-Pulse are a founding member of the J-League, the country’s top division) and Chibi Maruko-chan Land, a museum devoted to the anime character created by Shimizu-born artist Sakura Momoko. However, though I’m very fond of Chibi Maruko-chan, this time I was on the trail of another character one of Japan’s most colourful historical figues: Shimizu no Jirocho.

Jirocho could be considered a sort of Japanese version of Vidocq; like this French criminal who became a private detective and went on to found his country’s National Police, Jirocho was a yakuza turned public official and community leader.

Born in 1820, the second son of a local boatman, he was adopted by his maternal uncle, a rice wholesaler, who had no children. At the time, it was from this port that the feudal lords in central Japan sent their ‘annual tribute’ (tax) of rice to Edo, and the local shipping companies had a lot of power. When his adoptive father died in 1835, Jirocho became head of the family, but he liked to gamble and get into fights, and eventually gave up his business and became a bakuto (itinerant gambler), getting involved in organised crime and killing a few people in the process. Eventually, he became the leader of a 600 strong gang.

After a reign of terror, the yakuza became a well-respected man who is still revered.

For the next 20 years, Jirocho lived a fugitive life, constantly pursued by the police. However, during the bakumatsu (the last 15 years of the Tokugawa rule) he became a supporter of the imperial forces while becoming an instrument of reconciliation between the new Meiji authorities and the former Tokugawa rulers, which had repeatedly clashed both around Shimizu and at sea. In one particular episode, for instance, he also helped to recover the corpses of sailors killed in a naval battle between the shogunate and imperial ships and to arrange proper funerals for them. On this occasion, he famously said, “When you die, everyone becomes a Buddha. There is no difference between the government army and a rebel army”. Or maybe this is just an invention of his adopted son who, in 1884, published a popular book about his life, turning Jirocho into a folk hero.

When it comes to Jirocho, history and legend may be indissolubly intertwined, but the fact remains that as a result of his deeds, his past crimes were forgiven and in 1868, he was asked by the Governor General to provide security to Shimizu Port, completing his transformation from outlaw to public officer.

Whether a criminal or an appointed official, Jirocho was a natural born leader. He used his charisma (and perhaps even his former reputation as someone you had better not contradict) to help resolve disputes between underworld gangs and stop them from threatening local businesses. At the same time, he had a strong sense of community and worked ceaselessly to improve the provision of education, and Shimizu’s economy.

After leaving my backpack at the hotel, I retraced my steps to the waterfront where I knew I would find some of the sites related to Jirocho’s life. The placid Tomoe River, with its yachts and seabirds basking in the sun, almost gave the area the feel of a resort, but the shuttered shop arcade and old crumbling buildings were a reminder of a somewhat harsher reality.

It was near the river that I found Jirocho’s birthplace, a pleasant, almost quaint example of a Tokugawa-era merchant’s house. Though long and narrow, it was surprisingly well lit and had an atrium containing a well. Two old ladies, after overcoming their surprise at the sight of a visiting foreigner, made me sit in front of a large TV screen to watch a video about his life. They later told me that in 1854, the house was damaged by a large earthquake and the second floor had been added when it was renovated.

My pilgrimage next took me to Suehiro. During the latter part of his life, Jirocho tried to clean up his public image by getting involved in many philanthropic projects including opening this sailors’ lodge. The current building is just a copy, but it was constructed with reference to period photographs and includes sliding doors, support posts and other features that belonged to the original lodge.

When I climbed to the second floor, I was surprised to find five people sitting on the tatami floor and looking in my direction; two kimonoclad children were poring over a book while a man on the right, much taller than the others, had a sort of long cane in his hand. After recovering from my surprise, I realised they were dummies and, as I learned from a plaque in front of the tableaux, the tall guy was a blue eyed English teacher. It turns out that Jirocho wanted the people of Shimizu to be ready for the imminent opening of Shimizu port to international trade by learning English. Jirocho himself never received a formal education, but believed that studying English was important for the local youth.

This is just one example of how Jirocho, now a respected member of the community, tried to improve the local economy. Among other things, he pushed to expand the tea trade and appealed for the improvement of the port so that it could welcome the larger foreign steam ships. He also founded a shipping company to operate regular routes to Yokohama.

In the end, after a tough life, countless gang wars, and even one year in prison while in his 60s, he succumbed to a cold in 1893. He was 73 years old. However, his fame has outlasted him as scores of novels, films, TV dramas and even an anime series have contributed to further enhance his persona, turning the former violent gambler into a sort of Robin Hood.

G. S.