Faced with numerous difficulties, the Kochi Shimbun is not giving up and is seeking a way froward.

The Kochi Shimbun Headquarters is inside a modern-looking glass and reinforced-concrete building, its dark structure starkly contrasting with the white old-fashioned Prefectural Government Office located just a stone’s throw away. It’s as if Kochi’s main daily paper wanted to keep a close watch on the seat of political power.

On a freezing-cold afternoon, I climbed to the 8th floor of the Kochi Shimbun building to meet editor-in-chief Yamaoka Masashi and his deputy, Ike Kazuhiro.

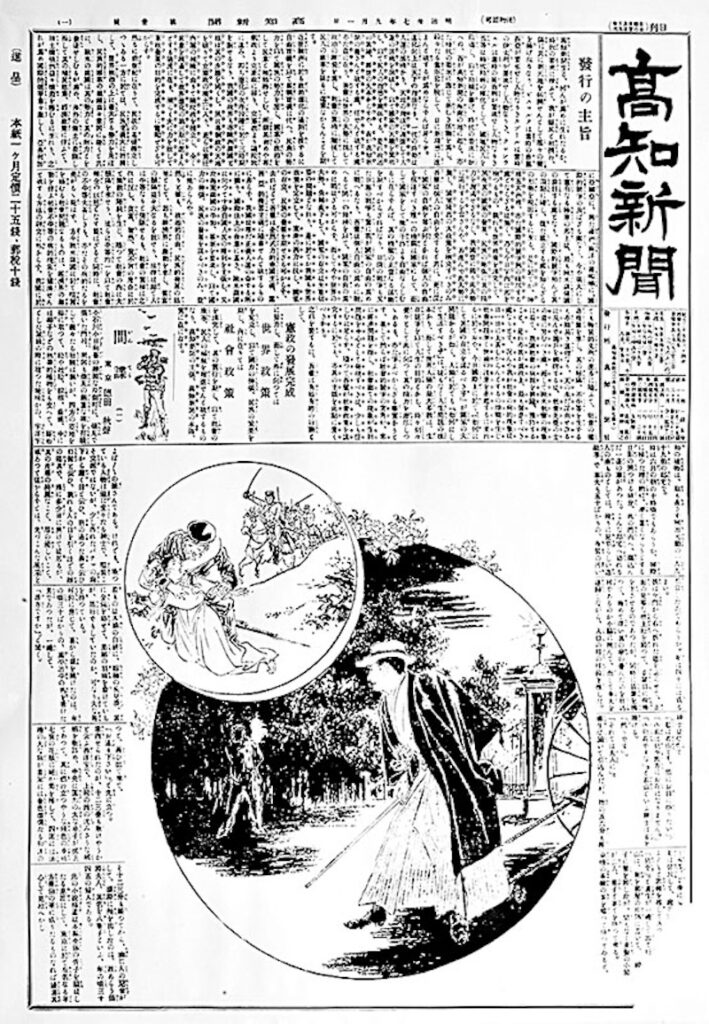

The Kochi Shimbun was established on 1 September 1904, during the Russo-Japanese War, when it broke away from the Doyo Shimbun. The latter periodical was the official newspaper of Risshisha, a local political organization founded by Itagaki Taisuke in 1874, which was at the heart of the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement. Later, in 1941, the two dailies merged again and became Kochi Prefecture’s only newspaper. This “reunification”, however, was the outcome of the campaign for newspaper control carried out by the Imperial Japanese Army, which dominated the government at that time.

“As this year is the 120th anniversary of our paper,” Yamaoka says, “starting in January, we’ve devoted some of our pages to the people who started the democratic movement.” Risshisha proclaimed fundamental human rights and set out goals for developing people’s knowledge, and advancing welfare and freedom. Several Kochi-born people played a central role in the alliance to form the National Diet and drafting the so-called Risshisha Constitution based on democratic ideals such as popular sovereignty, a unicameral parliament and human rights guarantees.

“Though some of those men were former samurai and belonged to the feudal regime, they were influenced by Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s thought,” Yamaoka says. “Among them, there was a man who studied French and translated his books into Japanese. And now, some 130 years after the proclamation of the first Japanese Constitution, we want to remember those people.”

Ike Kazuhiro tells the story of the “Newspaper Funeral” as a striking and humorous example of Kochi’s rebellious spirit and unique character. “The Meiji government severely suppressed the Kochi Shimbun because it sought political participation from the common people,” he says. “In 1882, the paper had its publication suspended five times, and on 14 July of the same year it was banned. In response, those involved launched an alternative periodical, the Kochi Jiyu Shimbun (Kochi Freedom Daily), and continued their protest movement, placing an ’obituary notice’ in the paper and calling for people to participate in the ‘newspaper funeral’.

“According to reports at the time, the coffin containing the Kochi Shimbun was paraded from the front of the newspaper’s main office for a distance of about seven kilometres by people in formal attire. A monk also attended the funeral, which was unprecedented in Japan, and made a scathing joke about those in power. More than 2,000 people reportedly attended, and the roadside along which the funeral procession passed overflowed with onlookers. Unfortunately, there are no photographs left of that funeral, but 125 years later, in 2007, the event was reenacted in Kochi City.”

Today, the Kochi Shimbun’s editorial department has 130 people, about 100 of whom are investigative reporters, making it one of the smallest newspaper companies in Japan. In 2022, it had a circulation of almost 145,000. “We are a small local paper,” Yamaoka says. “Then again, even Kochi’s population is quite small. I must admit, though, that we’ve seen better days.”

Indeed, after peaking at the turn of the century, circulation has decreased by 100,000 in the past 20 years. This said, its share in Kochi Prefecture is 88.36% (as of January 2021), which is very high even when compared to the rest of the country. Yamaoka himself has worked at the Kochi Shimbun since 1987 and became editor-in-chief three years ago. “Everybody wants to be a reporter when they join a newspaper, and I was no exception,” Yamaoka remembers. “But as people get older, they have less time to do their own reporting. I confess I don’t really like looking at the daily updates. This is a really bad time for newspapers, and there are times when I catch myself thinking about when I was working in the field as a reporter. Things are quite different now, but what can you do?”

Another recent source of problems is distribution. Though narrow in shape, Kochi Prefecture is Japan’s 15th largest prefecture and its coast extends for some 300 kilometres from end to end. Most of the region is also very mountainous. In the past, as was common everywhere in Japan, there were both morning and evening editions, but due to the prefecture’s size, only some areas could get the latter. For the same reason, the paper’s content varied depending on the location. However, the evening edition was suspended on 25 December 2020. The Kochi Shimbun, by the way, was the last general newspaper in the Chugoku and Shikoku regions to do this.

“Currently, there are 120 locations where the Kochi Shimbun is delivered,” Yamaoka says, “but finding people to distribute the paper is a daunting task. There aren’t many who want to do the job these days as it doesn’t even pay all that well.”

In big cities such as Tokyo and Osaka, international students and other foreigners are replacing those young Japanese who used to work in convenience stores or delivering papers. “In Kochi, however, there are still relatively few foreigners,” Yamaoka says. “I guess this place is a little hard to access and the barriers to living here are a bit high.

“On the other hand, since distribution is difficult, the national newspapers such as the Asahi, Yomiuri and Mainichi have always had problems getting established in this market, so you could say that the Kochi Shimbun was protected by its geography. That’s why we had a stable circulation until recently.”

In order to get more readers, particularly among the younger demographic, Yamaoka is now trying to usher the Kochi Shimbun into the digital age. “The main challenge for us, as it is everywhere, is digitalization,” he says. “Our paper edition is still our bestseller, but we also have a digital version. For example, for local readers, a monthly subscription to the paper edition currently costs 3,500 yen, but for a surcharge of 880 yen you can also read it on your smartphone. That’s been our subscription plan until now. The problem is, many people now don’t have that kind of money anymore. So now they can choose to subscribe to the digital version alone. Also, this year, for the first time, we’ll be sending our readers not only the paper digitally but also all kinds of fast-paced news and other things, with more pictures, videos, etc.

“I know we’ve started late compared to other newspaper companies nationwide. The fact is, the paper edition is sold through distributors, and until now they were strongly opposed to digitalization because, obviously, when people get used to reading on a smartphone, they forget about paper copies. Store managers put a lot of pressure on us. That’s one of the reasons why we put off taking the big digital step for so long. But we’ve reached a point where we can’t wait anymore. Anyway, more and more elderly people are watching the news on tablets and smartphones, so we need to create more digital products aimed at them.”

It’s no coincidence that Yamaoka mentions Kochi’s elderly population. “The data regarding our readership is a little old, but over 70% of our subscribers are over 60,” he says. “In Japan, they represent the hard core of newspaper readers. Kochi, in particular, is the second prefecture in the country in terms of an aging population.”

Unfortunately, though many elderly people keep subscribing faithfully to the Kochi Shimbun, they’re not going to be around for long, and getting young people interested is a major challenge for newspapers across Japan.

“We’ve come up with a new strategy,” Yamaoka says. “Our young employees have formed a team that is developing a new app that will probably be released this year. I’m not involved and I’ve had little time to follow this project due to all the other things I have to do in the editorial department, but I hear they’re doing a good job. They should be releasing new content in the next few months, focusing on subcultures and informational content, which young people can enjoy.

“Even if it doesn’t translate into a source of income right away, it’s important that we can create a dedicated app that everyone can use. Right now, we have fewer than 150,000 subscribers, but if we can get 200,000 or 300,000 people to have the Kochi Shimbun app in their pockets, they’ll easily be able to access more services, information and content, and we hope this is going to generate some money for our company. If you have any ideas, please let me know (laughs)!”

The younger generation are in everyone’s thoughts; even recently reelected Governor Hamada Seiji is looking for ways to keep them in Kochi and stop the population’s rapid aging process. Yamaoka, on his part, is still sitting on the fence about the performance of the governor’s first administration. “It’s still hard to judge,” he says. “For many years, Hamada was just a public servant, and as a politician he’s not shown strong leadership qualities. Granted, his first term was quite difficult because he spent two or three years fighting the pandemic, so now the time is right for him to leave a mark with new policies that reflect his personality.

“As I said, he’s a former bureaucrat who does what is expected of him, one step at a time, without trying to change things radically. I think he’s an excellent administrator, but he’s by no means the type of leader who will warm everyone’s hearts and minds with his speeches. Last year he was reelected thanks to the fact that there were virtually no opposing candidates. The only real contender was a member of the Communist Party. For many years, Kochi was actually a Communist stronghold, but things seem to have changed.

“As journalists, we want to keep an eye on what Hamada is going to do. So far, I don’t think we’ve given him too much praise, but I’m looking forward to seeing what his new administration is capable of.”

One thing that bothers Yamaoka is the growing urban concentration of Kochi’s population. “Out of Japan’s 47 prefectures, Kochi ranks third in terms of population concentration after Kyoto and Miyagi,” he says. “However, the rural areas in those two prefectures are not as large as in Kochi. In practical terms, about 48% of people in our region live in Kochi City, and it’s probably going to increase. What is happening is that small towns and the countryside are being neglected. Many things are missing in those places, and schools for children are disappearing. That’s one of the reasons why young people are increasingly moving to other prefectures to study and work, and if we don’t solve this problem quickly, the population will continue to shrink. This one, however, is not Hamada’s fault. Former administrations have implemented policies such as reducing schools and closing hospitals, making it difficult to live outside the main cities. This has been going on for decades.”

The housing problem is one of the local issues that the Kochi Shimbun has been following closely. “We have been serializing this topic for some time now, and have published about 70 stories,” Yamaoka says. “More and more apartment buildings are being built in Kochi City as people are flocking to this area. The other side of the coin is that akiya (vacant houses) are everywhere. As a matter of fact, Kochi is the prefecture with the most akiya. Also, many elderly people take buses and trains, but public transport is getting scarce, too.”

Ike-san, for his part, led an investigative team to report on whitebait poaching, an illegal activity in which yakuza are involved. This difficult investigation, conducted in 2021, was highly praised and won the Japan Newspaper Association Award that year. “Whitebait is traded at a high price,” Ike says. “It’s also called ‘white diamond’ and is subject to rampant poaching and underground distribution by organized criminal groups. Our reporting team conducted interviews for five years to get to the bottom of this situation, and published a three-part series (39 articles) between January and June 2021 on fishing, distribution and regulation. When we approached them for an interview, many people kept their mouths shut or told us to stop. Nevertheless, our reporting team didn’t give up. This series is neither big news nor a national scoop. It’s just classic reportage based on steady investigative work to unearth what we think is an important local issue.”

As Japanese newspapers all face a difficult situation, Yamaoka believes that collaboration is the key to their survival. “The local newspapers network has become stronger over the past five years,” he says, “and I think we’ve a chance to create a new system. In my opinion, two main problems affect newspapers. First of all, dailies cannot compete with TV and the internet in terms of delivering news quickly. By the time a story appears in the newspapers, it’s already been featured online. In this respect, there’s not much point in publishing the same news. The other problem is that newspapers all too often rely on large news agencies such as Kyodo News to get the stories. If you have a look at the Kochi Shimbun, you’ll find both content that was created by our editorial department and stories we got from a news agency. These latter articles, of course, are the same in every newspaper. This practice is outdated and has no future. I think it’ll probably disappear soon.

“Instead of relying on major media outlets, local newspapers should act like a cloud network, sharing and exchanging stories and disseminating information readers can’t get otherwise. Throughout Japan, there’s a treasure trove of interesting local stories that only a local journalist can write. NHK can’t do it; the Asahi Shimbun can’t do it, but a paper from Fukushima, Niigata or Kochi can.

“A trend is starting to emerge where small newspapers all over the country work together to protect local journalism. I’ve been talking with several friends in the industry and I think that offering stories the readers can’t find anywhere else is the path we should follow if we want to survive. In any case, if newspaper companies don’t find a new approach, things will become increasingly difficult.”

Gianni Simone

To learn more on Kochi , check out our other articles :

N°138 [FOCUS] Battling to attract people

N°138 [TRAVEL] A wealth f beauty

N°138 [ZOOM GOURMAND] Yuzu today, yuzu forever

N°138 [CULTURE] For the love of nature

Follow us !