Before being published in widely distributed magazines, many work their magic in alternative publications.

Before being published in widely distributed magazines, many work their magic in alternative publications.

In the age of blogs and electronic communication, Japan seems to be one of the few countries left where people consistently enjoy reading printed media and such independent events as the Tokyo Art Book Fair are visited every year by thousands of young enthusiasts.

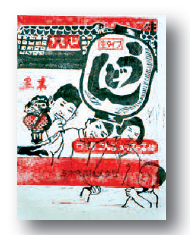

A small but fascinating niche is represented by zines – cheap, self-published booklets with a tiny print run (100-200 copies), generally photocopied and created either in the classic cut-and-paste style typical of the DIY philosophy or with the help of a computer. Zines belong to a parallel editorial world and are usually traded with friends or sold by mail or at independent festivals. In Japan in particular, the zine scene is very small and mostly flies undetected under the radar of mainstream culture. The only notable exception are dojinshi or underground comics that typically take characters from established publications or famous novels and movies and place them in new stories, alternative relationships or parallel worlds. Some of them are so popular that they sell thousands of copies. They clearly infringe copyright laws but the publishers seldom sue them because they ultimately play an important role in creating a faithful fan base. 35-year-old Narita Keisuke (see interview) is the leading figure of the local zine scene. For years he has been promoting a DIY lifestyle through his “infoshop” Irregular Rhythm Asylum (IRA) and the Zinester Gatherings he periodically organizes in Tokyo. His Expansion of Life zine explores such themes as veganism, feminism and queer identity. While Narita comes from the older angura (underground) scene, the new generation is represented by people like Nakano Nami. Her comics (such as the ironically titled Romantic Friendship) have nothing to do with the cute manga that are so popular abroad. Her erotic stories often feature lewd dialogue and are closer in spirit to the old Garo magazine or American comics. As Nakano explains, “Rather than trying to shock my readers, I only want to say that we should live more spontaneously, without hiding behind a mask”. As in other countries, current Japanese zines are ideologically connected to the punk scene or the countercultural spirit of the 1960s and often focus on music and alternative lifestyles. Currently the best-known music zine is probably El Zine, which covers both the international and local punk/hardcore scene and whose fame has crossed the national borders. Women are well represented and they often contradict the stereotypical image of the demure Japanese female. Women like Yayoi for instance who, published Catch That Beat! between 1996 and 2002. “Apart from interviewing my favorite bands, like Le Tigre,” she says, “or people like sex shop owner Kitahara Minori, I wanted to share with my readers our ideas about sexuality and politics. I was often criticized for being a feminist”. Now 35, Yayoi is an office worker and has exchanged her t-shirts and jeans for a business suit, but has not forgotten the Riot Grrrl’s philosophy. Her message has been followed by people like Kanatin and Yumeko who put together the NAMAE zine. Their mission is to “sail the seas of love and joy with the help of a map of the imagination”. Less politically committed than Yayoi, the dynamic duo behind NAMAE write in a “pop & cute” style of their invention which often borders onto nonsense. Yet they present different sides of alternative culture both in Japan and in other East Asian countries. Popdrome Service is another Tokyo-based group with an eclectic spirit. Their photocopied zines (Carson Zine, Kathy Zine, Romangetic Island) mix punk, comics and children’s illustrations while displaying a highly subjective vision, which transcends social conventions.

The world of alternative fashion is featured in a number of zines that approach this subject in different ways. While Cantera prefers the cute side and Jasmine Zine features elegant black and white pictures that are closer to mainstream publications, other zines look at fashion from an alternative, lefty perspective. A typical example is Naturalo Punk, which claims to feature “fashion for everybody” and displays a somewhat rougher approach to the typical trends of what is usually called “street fashion” that in Japan has a long tradition. A growing trend is represented by art zines – higher quality booklets that are usually printed in colour on good quality paper and are comparatively more expensive. Works like Miyazaki Chie’s Watermelon Zine can be found more easily in art bookstores and galleries than at DIY distributors like Narita’s IRA and unlike other independent publications, they are often just a way of advertising one’s own work outside the mainstream network. That’s why they are often dismissed by the more hardcore side of the DIY scene as something that has nothing to do with the underground, rather a way of getting access to the commercial art circuit. An interesting exception is a free photo zine called Doo Fanzine by Osaka-born artist Terasawa Dougen. Its first issue focuses on graffiti art and falls into the local tradition of what the author calls “street snapping”.

Gianni Simone