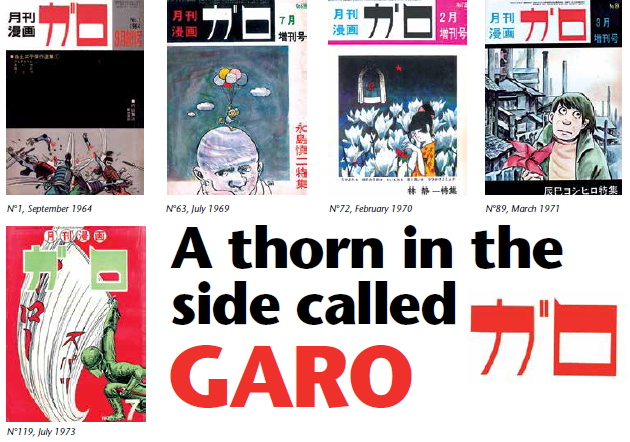

First published just fifty years ago, this magazine has not only had an impact on the world of manga, but also on Japanese society as a whole.

First published just fifty years ago, this magazine has not only had an impact on the world of manga, but also on Japanese society as a whole.

Just fifty years ago, Japan was ready to move on and leave it’s past behind. Tokyo was about to host the Olympic Games and launch the first fastest train in the world (the Shinkansen bullet train). Four months previously, the country had joined the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a symbol of Japan’s economic success barely 20 years after the country’s surrender. Japanese citizens had worked hard to rebuild their economy and bring it back up to the same level as the Western powers. In the same year, 1964, Japanese citizens gained the right to travel abroad freely. For the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which had been running the country for the previous ten years, everything was going well and it intended to broadcast to the world a positive picture of the archipelago, at a time when all eyes would be on the country hosting the Olympic festivities.

Yet behind the veneer of success, many problems remained and there was unrest among those Japanese left behind by the economic growth, or dissatisfied by the way the country was being run. By this time there had already been two major protests, when a large part of the population took to the streets to demonstrate their opposition to the signing of the USJapan Security Treaty that, according to them, would make Japan little more than a vassal of the US. In high schools and universities, there was great discontent about foreign policy and especially about the rigid system of education. It was in this context that a new magazine devoted to manga made an appearance. Called Garo, it was put together to allow one of its founders, Shirato Sanpei, to explain to the very young that the world they were to grow up in was far from being a bed of roses. Quite the contrary, it promoted the message that it was essential to fight hard to make the world a better place. He intended to “educate” these young children by means of his seminal saga, Kamuiden. In fact, at the start Garo was not aimed at adults or even young adults. As early as its second issue, the monthly magazine proudly flagged up that it was a “junior magazine” to show that it was targeted mainly at children. One of Kamui-den’s main characters is a child called Shosuke, who sets an example through his behaviour as he tries to help his village free itself from the yoke of it’s feudal lords.

However, there were many obstacles for Shirato to overcome in his attempt to seduce younger readers. At 130 yen for 130 pages, Garo was a bit too expensive for pocket money, especially compared to Shonen Magazine or Shonen Sunday, both on sale for 50 yen, with pages full of heroic role models and free gifts. Even though it didn’t succeed with young children, the magazine quickly became a hit with student readers. This convinced the management to drop the strap line appealing to younger readers from May 1966. This was an important development for Garo, which saw its contents change with the arrival of new authors who did not have children in mind. Themes were tackled more subtly and required more thought to understand them. Meanwhile, intellectuals were invited to contribute to the magazine to discuss the great issues of their time. The magazine’s content became more complex to meet the expectations of more discerning readers. Shirato Sanpei also adapted Kamui-den to fit with this new strategy, and sales really took off. 80,000 copies of the monthly magazine were sold in 1967, a rate that was maintained until the early 70s, after which it experienced a slow decline, finally disappearing in 2002. While university culture remained buoyant, Garo supported the trend and published new essays in each issue to convince readers of the need to rethink the way Japanese society was evolving. Mizuki Shigeru, well known for his stories about ghosts and other traditional Japanese characters, published many stories in Garo denouncing the country’s modernist excesses and the risks inherent in becoming a country totally in thrall to technology. In November 1965, it published a story about Tokyo being destroyed by giant plants created by pollution.

In his own way, he blew the whistle at a time when industrial accidents were multiplying, resulting in ever increasing casualties. A great number of stories published by the magazine tried to warn the Japanese about the determination of those in power to sweep away the cherished Japan of yesteryear, to the detriment of the population. It is not surprising that authors like Tsuge Tadao and Tatsumi Yoshihiro often discussed these issues in their dark stories. Others, like Takita Yu (1931- 1990) cultivated a kind of nostalgia for working- class Japan, which though not rich, was socially cohesive. His best-known work, Singular Stories from the Terajima District (Terajimacho kidan), released between December 1968 and January 1970, appeared around the same time as the film series Otoko wa tsurai yo [It’s hard to be a man], and addressed the same subject, one that the Japanese were to firmly support for more than 25 years. The slow atrophy of social ties and communication between people was also a popular theme for Sasaki Maki who, while mostly dealing with the Vietnam War, did not shy away from illustrating this worrying development by drawing speech bubbles that were either left empty, or filled with words completely out of context. Fifty years later, as Japan is again faced with making crucial choices, it is of great regret that there is no longer such a publication capable of encouraging and adding to contemporary debate and reflection.

Odaira Namihei