During its wide-ranging attempts at changing people’s attitudes towards Japan’s past history and postwar constitution, Nippon Kaigi has gained increasingly strong support from a number of conservative and right-wing groups and individuals. One of the more outspoken personalities who has emerged since the late 1990s has been Kobayashi Yoshinori, a best-selling essayist and comic artist. The author of over two hundred books and manga, Kobayashi started as a comic artist in the mid-1970s, satirizing the Japanese education system (for example the testing obsessed “examination hell”), while in the 80s he targeted social privilege during the high-flying years of the bubble economy and won the 1989 Shogakukan Manga Award for children’s manga for Obocchama-kun (Little Princeling).

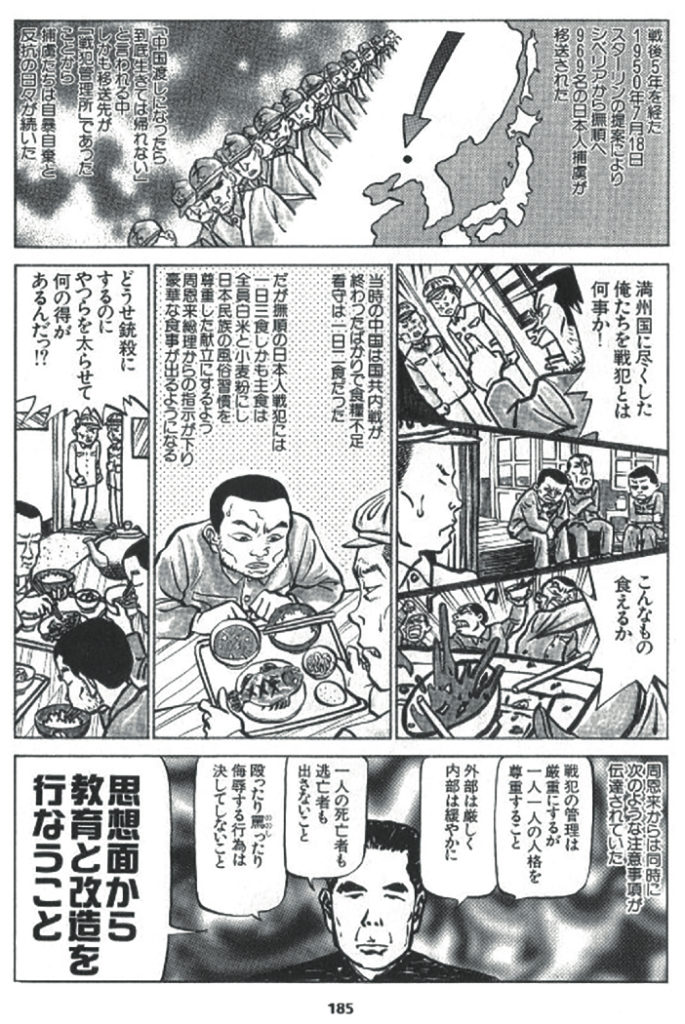

Kobayashi’s name became known outside manga fandom in the 90s when he began to publish a series of manga essays called Gomanism Sengen (Declaration of a Philosophy of Arrogance), in which he criticized and made fun of several aspects of Japanese society (doomsday cult Aum Shinrikyo was so “displeased” with Kobayashi’s antics that they famously tried to kill him in 1993). Most importantly though, Kobayashi used his penchant for controversy and argument in order to call for a conservative revision of Twentieth-century Japanese history in his usual arrogant and abrasive manner.

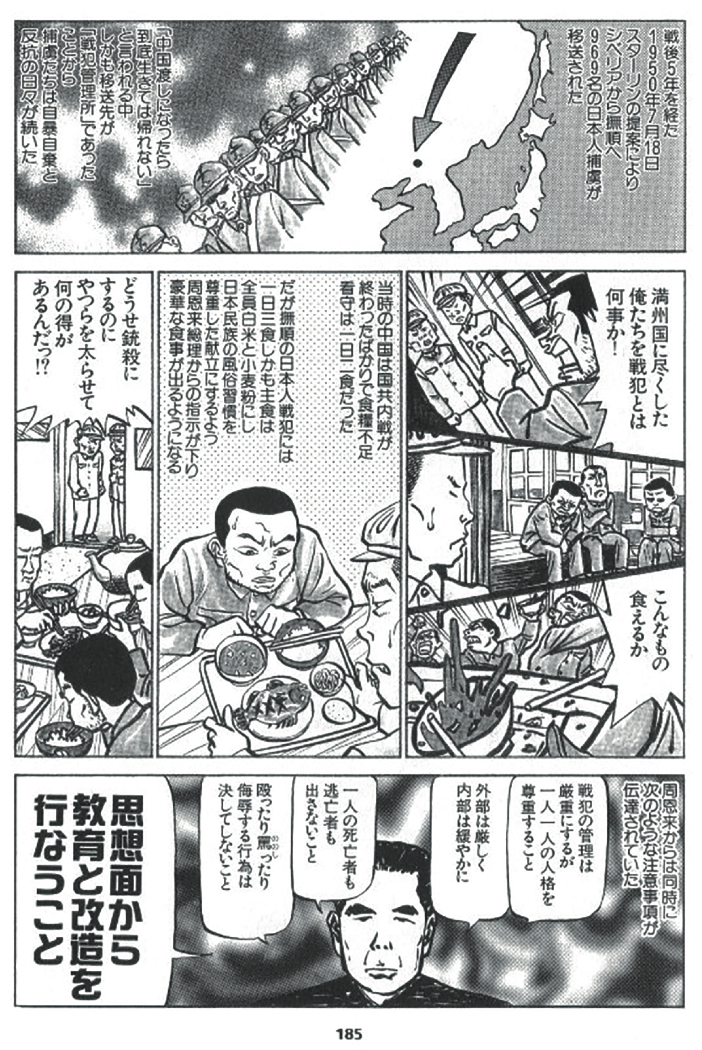

The book that caught the most attention – Sensoron (On War, 1998) – was only one of several works that heralded this growing nationalistic attitude toward Japan’s past. Other revisionist essays of the time include Akiyama Joji’s Chugoku Nyumon (Introduction to China) and Yamano Sharin’s Ken-kanryu (Hatred of the Korean wave), but Sensoron was by far the most successful, selling around 650,000 copies. As he later stated, Kobayashi conceived Sensoron as “something that intellectuals cannot write – something that young people find pleasure in reading and become completely absorbed in, and yet is not light but profound”.

Kobayashi’s populist, non-intellectual approach is exemplified by the manga technique he has consistently used throughout the Gomanism Sengen series: every book features a Kobayashi lookalike – a symbol of the common man – who uses logic and common sense in order to refute several issues related to WWII by pointing out the weaknesses in the accepted view of history (i.e. that of progressive historians and intellectuals). Among the topics he tackles are the so-called “comfort women” (women who were forced into sexual slavery by the Imperial Japanese Army), the Nanking Massacre and Japan’s war of aggression in Asia.

In the case of the comfort women for example, Kobayashi argues that “There were no women abducted by the Japanese military and turned into sexual slaves. There were women who sold their services to Japanese soldiers of their own volition or because of unavoidable circumstances”. As a consequence, he castigates surviving comfort women for being liars who are trying to blackmail the Japanese government into giving them money (one of his recent tirades on the subject can be found on You Tube, youtube.com/watch?v=Hpa- Nofy5bwQ&t=25s). The general idea informing this and other books by Kobayashi and other right-wing writers is that Japan went to war justly, in order to free other Asian countries from colonialism.

The problem with Sensoron is that Kobayashi only chooses historical sources and evidence that appears to back his opinions, and ignores any that contradicts his point of view. Much of the data, even when correct, is blown out of proportion and used out of context, leading to conclusions that would never stand up to a serious historical evaluation. Even so, his clever mix of pop culture (manga), anti-elitism and faux-scientific analyses have won Kobayashi many admirers, making him a sought-after columnist and TV commentator.

successful in Japan.

In 2010 Kobayashi demonstrated his complex relationship with the Japanese conservative establishment when he spoke with Abe Shinzo (then leader of the opposition LDP) for a collection of interviews entitled Kibo no Kuni Nippon (Japan, a Country of Hope). In this interview the two men agree that Japan’s strong prewar moral values were destroyed by the American occupation, and that the comfort women system (a real obsession for the political right) was, after all, practised by all the participants in WWII, with only Japan being criminalized because it was defeated. However, Kobayashi criticizes Abe for giving in to American pressure on historical issues.

In the last few years, particularly after Abe began his second stint as Prime Minister, the manga artist has increasingly found fault with the Japanese government, showing a more ambivalent (some would say ambiguous) attitude towards conservatism. In 2013 in particular, Kobayashi expressed his opposition to the new secrecy bill in a front page column in the daily Asahi (a very surprising choice, as this liberal newspaper is traditionally one of the conservatives’ favourite targets). Kobayashi compared the secrecy bill to the Peace Preservation Act of 1925, pointing out the fact that the new bill could be used to censor any kind of opposition and turn Japan into an authoritarian state.

Kobayashi’s new ideological position was further confirmed at a press conference he organized in August 2015 at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan in Tokyo. At this event, Kobayashi began by saying that people consider him a conservative; indeed, he is one in so far as he believes in conserving Japan’s identity, but he has changed some of his opinions following the debate on security legislation. “For instance, I feel strongly that the Japanese constitution should be revised and allow the so-called Self Defence Forces to become a military force,” he said, going on to add that: “However, I disagree with all those conservatives who want to preserve my country’s subordinate relationship with the United States”. He then gave the Iraq War (an event he has already covered in his books) as an example. “Now, everybody agrees that it was a war of aggression and it was wrong to invade Iraq,” he argues, “But Prime Minister Abe and the whole conservative establishment in Japan keep denying this. They don’t want to say it was wrong to follow America into war, and the reason is that Japan always has to follow American foreign policy.

The Japanese should be able to discern between a just war and a wrong war and decide if they want to commit themselves to that war. In the last 50 years, America has embarked on many wars of aggression including Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq. Every time they end up destroying those countries. The way I see it, in the past, even Japan has engaged in wars of aggression, but from now on we should avoid them”.

Regarding the constitution, Kobayashi said that he wasn’t among those who think that Article 9 should be preserved at all costs. “I disagree with the pacifist movement because, for me, Article 9 is the other side of the American military presence in Japan,” he explains. “But I believe that we must defend constitutionalism at all costs. That’s the only way people can put a check on the government”. Quite uncharacteristically for once, Kobayashi praised the USimposed constitution, explaining that the good thing about it is that civilian control over the military is clearly delineated.

At the end of the press conference he was asked if he considered the Great East Asia War (i.e. the Asia-Pacific War) to have been a war of aggression. He said that when Japan invaded China in 1937, that was obviously a war of aggression, but that in order to understand what happened we should look at the bigger picture. “In 1853 Commodore Perry arrived in Japan and forced our government to accept unequal treaties with the US and other Western countries,” he said. “Japan was suddenly thrust into the age of imperialism and was forced to become a colonial power itself in order to survive and be treated as an equal. We won both the Sino- Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese war. As a consequence, citizens began to respect their military leaders and failed to keep their foreign policy in check. Having said that, I think that Japan found itself in a situation where it had no choice but to fight against the US. After all, Japan would have liked to remain isolated from the rest of the world. It was forced open, and that put in motion a process that culminated in the war against the US. You may say it was our destiny”.

In the end, Kobayashi seems to be a man at a crossroads, trying to regain some of his lost charisma by repositioning himself along slightly more liberal lines without renouncing his brand of right-wing patriotism.

JEAN DEROME

Leave a Reply