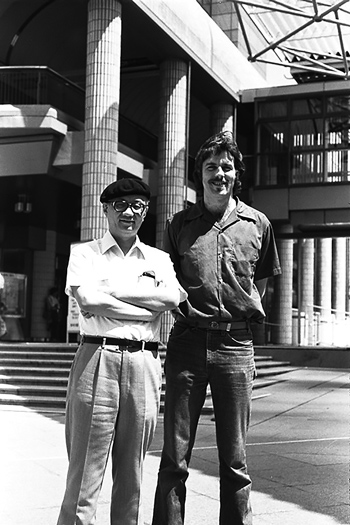

A major player on the art scene of the period, Yokoo Tadanori recalls his years in this emblematic district.

Yokoo Tadanori in his studio designed by Isozaki Arata, 15 March 2018.

world-renowned graphic designer and painter Yokoo Tadanori is famous for his iconic posters and easily recognizable style. However, less is known about the role the artist played in the second half of the 1960s, when he collaborated with the leading figures of Japan’s cinematic and theatrical new wave. I had a chance to talk with Yokoo about those intense years of activity when I met him at his Isozaki Arata-designed studio in Tokyo’s western suburbs.

You moved to Tokyo from your hometown in Kobe in 1960, during the first Anpo protests. What did you make of the student movement?

Yokoo Tadanori: At the time, I was 24; I was already working and hadn’t even been to university for a start. I’d gone straight from high school to the printing company. So it was hard for me to relate to the student’s anger. Also, it would have been hypocritical to rail against the establishment while we were doing advertising work for big companies (laughs). In a sense we were selling our souls on behalf of capitalism. But one of the directors at my company, Kamekura Yusaku (who later designed the posters for the Tokyo Olympics), insisted that we had at least to get a feeling of what was going on in Japanese society at the time. So we all climbed into a taxi and went to the Diet Building where a big demonstration was taking place. It was crazy, I really didn’t understand what was going on, and on top of that I ended up with a broken thumb and couldn’t work for six months.

What happened?

Y. T.: We got there without really thinking about what we were doing, but when we arrived at the Diet, it was complete chaos: the riot police on one side and the students on the other. Bricks, wooden sticks and iron pipes were flying everywhere. Of course, in those conditions you’re going to get hurt sooner or later. Anyway, we found ourselves with right-wing students on one side and left-wingers on the other. And we were in the middle holding a placard with a white dove on a blue background — the peace symbol.

In the second half of the 1960s you had an opportunity to work with some of the stars of the Japanese avant-garde such as Oshima Nagisa, Terayama Shuji, and Kara Juro. How did you meet them?

Y. T.: Actually, the first person I met was photographer Hosoe Eikoh, around 1962. I heard that he’d made a collection of portraits of Mishima Yukio, who was one of my idols. In my youthful naivety, I went to his studio, and asked him to let me design the book – what would become Ordeal by Roses. Of course, I didn’t get the job, but some time later, I got a call from Hosoe who told me that Terayama was working on a musical and he wanted me to design the poster. Even that project fell through, but I got close to Terayama, and that was the start of our friendship and working relationship. Even when we didn’t meet, we used to call each other every day. Sometime later, I met Kara too. I was having coffee with Terayama at TV broadcaster TBS, and he introduced me to Kara. He was a few years younger and totally unknown to me. I remember he had this smooth, child-like face and looked like Momotaro [a popular hero of Japanese folklore whose face looks like a peach]. Soon after, he asked me to design the flier for his new play, and that was how I went on to do John Silver’s poster and other projects for his Situation Theatre troupe. In other words, I first met Terayama, but started working with Kara before I actually did anything with Terayama. Finally, Tanaka Ikko, who was my senior at my company, told me that butoh dancer Hijikata Tatsumi was looking for someone to make a poster for his show. Tanaka was into Modernism, and MEMoRIES Yokoo, oshima and the others A major player on the art scene of the period, Yokoo Tadanori recalls his years in this emblematic district. found his style didn’t suit butoh, so he passed on the job to me. And so you see, job opportunities are born of these human interactions, and human bonds are strengthened by working together.

Speaking of human relations, how would you compare your collaboration with Kara and Terayama?

Y. T.: Terayama was extremely intelligent and very good at dealing with people. He wrote so quickly, he churned out one script after another. When the script was ready, he’d explain what he wanted from me. The problem was, his explanation was so thorough that in the end there was nothing for me to add. I found it boring to work on these projects. Kara was the complete opposite. He’d talk about a new play before the script was even ready. I’d say, ‘How the hell am I supposed to work like this?!’ So he’d try to explain the ideas spinning through his mind. He was very intuitive and impulsive, while Terayama was logical. Kara had this physical, almost animal approach to his material, it was hard for him to put it into words, so I had to make an extra effort to join the dots. But because of that, I find my work for Kara is superior to the work I did for Terayama… Sorry Shuji (laughs).

How about Hijikata?

Y. T.: Oh (laughs)! With him, you weren’t even sure he was actually speaking Japanese. It was all Greek to me. So I’d work on a poster without having the faintest idea of what he wanted from me. But somehow, he was always happy with the result. ‘Yokoo-san, nobody understands me the way you do,’ he’d say. ‘How do you do it?’ Beats me!

I know you are a big fan of Mishima Yukio.

Y. T.: Yes, I met him a little later, in 1965. Of course he was a star in comparison with our underground group. He approached me when he wanted to do something with kabuki or bunraku. His method was different again from the others. He’d actually make a sketch of the poster he’d have in mind and add ‘I’ll leave the rest to you’. But he wouldn’t leave me alone! He’d constantly peer over my shoulder. I found it so annoying.

For Terayama’s troupe, Tenjo Sajiki, you even worked as the stage designer, didn’t you?

Y. T.: Yes, it was an interesting job, even though I was constantly struggling with limited budgets. And anyway, I only stayed for a short time, mainly because I didn’t get along with Higashi Yutaka, the stage director. I had a good relationship with Terayama, but he was always busy working on new projects, writing books and articles, so he left the day-to-day management to Higashi, who’d just finished university. We worked together on Tenjo Sajiki’s first three plays, but I had a run-in with Higashi while working on the third one, Kegawa no Marii (Mari in Furs). So I left the company, and Higashi followed me a little later, in 1968, to form his own company, Tokyo Kid Brothers.

What happened between you and Higashi?

Y. T.: Each play was staged at a different place. Our debut work, Aomori-ken no semushi otoko (The Hunchback of Aomori Prefecture), was performed at the prestigious Sogetsu Art Centre, which was the home base of Ono Yoko, composer Takemitsu Toru, novelist and playwright Abe Kobo, and others. However, Oyama debuko no hanzai (The Crime of the Fat Girl from Oyama) was staged at Suihiro-tei, the last remaining vaudeville theatre in Shinjuku, and Kegawa no Mari was performed at the Shinjuku Bunka Art Theatre. Now the problem with the Shunjuku Bunka was that it was designed to screen films, and the so-called stage was actually just a narrow empty strip. The set I’d designed was too big, but it was Higashi’s fault as he’d given me the wrong measurements. When he tried to cut it down to size with a saw, I couldn’t take anymore and just left. I later heard that Miwa Akihiro, who starred in the play, managed to repair the damage just in time for the performance.

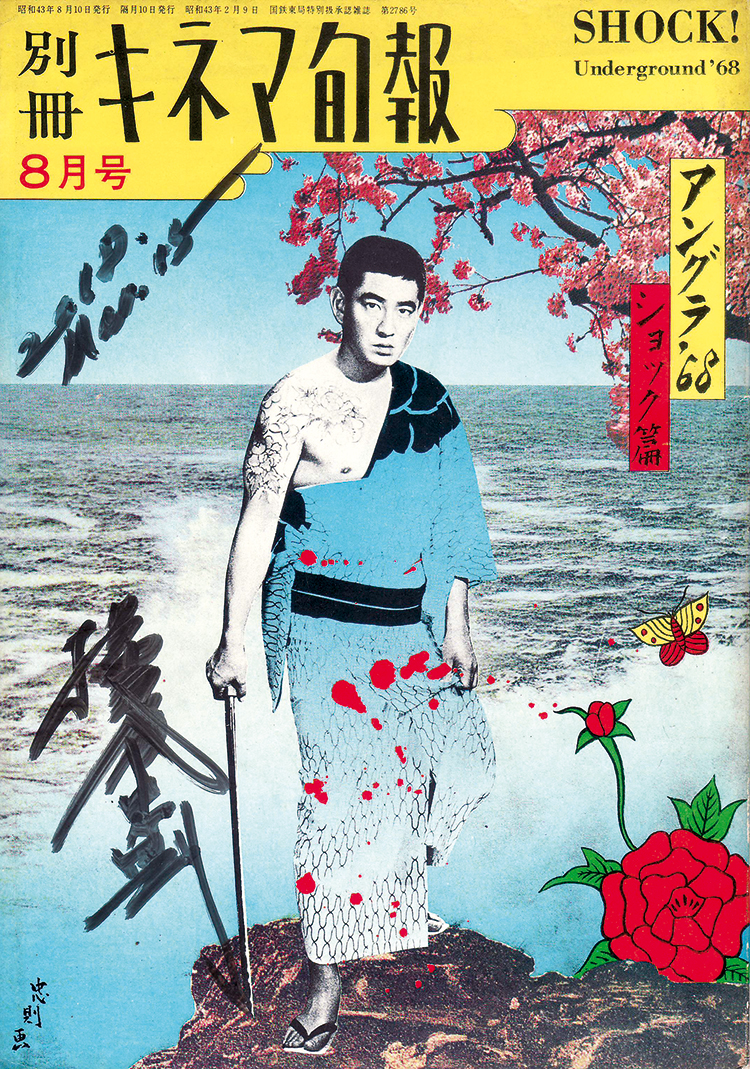

The cover of the special issue of Kinema Junpo, August 1968, with the actor Takakura Ken, signed by Yokoo.

Your graphic work from that period has become justly famous. You created an iconic ‘Yokoo look’ that’s easily recognizable. How did you arrive at that look?

Y. T.: As I said, in 1960, I moved to Tokyo from Kobe and worked for advertising agency Nippon Design Centre, which was pushing Modernism in Japanese design. Coming from a very different environment, I’d never come across these new ideas. Instead, I decided to make use of the images and atmosphere that I recalled from my childhood – the local festivals; the picture story shows (kamishibai) I enjoyed as a kid; the labels my adoptive father put on the kimono fabric he sold – all the pre-modern design I grew up surrounded by. I was clearly going against the grain, and the top critic at the time told me so: what did I think I was doing, denying the new direction in Japanese graphic design?! But even though my approach was rejected by the other designers, it was embraced by Terayama, Mishima, and other intellectuals, and by the younger generation. Ironically, my old-world style was seen as something fresh.

Do you find it strange that the students liked your work?

Y. T.: Well, those youngsters were supposed to be all for progress and modern ideas. But, apparently, they were attracted by my brand of ‘traditional Japan’. There was something contradictory about them, because on the one side they were left wingers and belonged to Marxist groups, but on the other hand they were all fans of actor Takakura Ken whose yakuza films were about traditional, even conservative values. The students at the time had a lot of energy but didn’t know what to do with it. In particular, they didn’t really follow a specific ideology. They just wanted to throw their energy at something.”

Were you influenced by any artist or genre in particular?

Y. T.: It may sound strange, but I didn’t really like the world of graphic design. I was more attracted to film and literature, music and theatre, and art, of course. I was essentially into foreign things: American Pop Art, French Nouvelle Vague and Nouveau Roman. Each one of them was a source of inspiration.

Let’s talk about Diary of a Shinjuku Thief. How did you end up in Oshima’s film?

Y. T.: I didn’t know Oshima well, but I knew his cameraman, Yoshioka Yasuhiro. I loved films, of course, but I’d never acted in my life. So when Yoshioka told me that Oshima wanted me to take part in his film, I was very surprised. I had many doubts about being able to do the job, but, apparently, my being inexperienced was the reason Oshima chose me. Actually, I was sort of tricked into playing in Diary….

What do you mean?

Y. T.: Well, at first I was told it would be an action film with lots of gun battles, and I’d be playing a hoodlum. I was very excited, but then Oshima said Diary was better suited for me. In the end he chose another actor, Tamura Masakazu, for the action film, and I ended up working in Diary, which could be considered a symbol of New Wave cinema, but for me it was much less interesting.

Still, it’s an important documentary of the period.

Y. T.: Yes, but I was already 32 at the time. Can you imagine a 30-something guy playing a student during the Anpo and anti-Vietnam War demonstrations (laughs)?! I really didn’t know how that could possibly work. Then I told myself it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, and anyway, if things went wrong, only the director would be blamed. So I accepted his offer. Then Oshima – who’s never been good at dealing with women – asked me to name an actress for the film. I found that strange too, but, anyway, I was a fan of Asaoka Ruriko, so I suggested her. Asaoka, at the time, was the star of Nikkatsu films and a box office star. In the previous ten years, she’d appeared in more than 100 films. But when she read the script, she didn’t like all the risqué scenes and turned down the film. Eventually, he chose Yokoyama Rie, a theatre actress who was new to film.

Do you remember any particular episodes during the making of the film?

Y. T.: To my surprise, the script was full of empty pages. Every day, when the shoot was over, Oshima would write a few new pages for the next day, depending on the mood on the set. Nobody, including Oshima himself, knew what the final story would look like. It felt like improvisation every time. I guess you could call it the New Wave approach to making films. Then you had these scary types hanging around, like co-writer Adachi Masao, who later joined the Japanese Red Army. I was in a daze, never sure about what I’d be asked to do next. Also, as a non-professional, learning new lines at short notice was always a challenge. I could never remember them. On the plus side, I didn’t have to say exactly what was written in the script I was handed, and Oshima didn’t even mind my Kansai accent.

Was Oshima a demanding director on the set?

Y. T.: He was very strict with everybody but me, probably because I had no experience whatsoever. I guess he was afraid that if he got angry with me, I’d quit the film. So he was soft on me. On the other hand, I was scolded by the assistant director for not hitting my mark or forgetting my lines. But Oshima didn’t mind so much. After all, I wasn’t very important: the film’s real protagonist is Shinjuku itself.

How was your relationship with Yokoyama Rie on the set?

Y. T.: As a non-professional, I was expecting her to take the lead, but like me, she was rather new to films. Then, just before a sex scene, she told me: ‘You know, I’ve never even kissed a man. What shall I do?’ What?! Why are you saying this to me?! As if I could do something about that. Well, I guess for her, this film what quite a trial.

One of the more famous scenes in the film is the opening, when you get caught by Yokoyama stealing books at the famous Kinokuniya bookstore in Shinjuku. Were you into reading at the time?

Y. T.: Not at all! I was so busy with my work that I had no time for reading. I’d just buy books and put them aside for future reading. Anyway, that was another interesting shoot. Oshima told me to go in, choose a few books I liked, and leave the shop without paying. So I began walking around, not even knowing where the cameras were hidden. I chose three books and made for the stairs, but in order to reach them, I had to pass in front of the cashiers. I was so scared, because nobody in the shop knew about the shoot, not even the sales assistants. Only Kinokuniya’s big boss, Moichi Tanabe, knew what we were doing. I guess Oshima was a little disappointed that everything went smoothly. Probably he was hoping I’d get caught or something (laughs).

Did you have any favourite spots in Shinjuku?

Y. T.: I often went to Najia, a bar that was always full of artists and intellectuals. I didn’t drink, but I liked to talk to the mama-san, Mariko, while having some rice balls or fried rice. It was also interesting to observe that crowd, a sort of culture mafia. Sooner or later they would start arguing about something, and, typically, it would escalate into a free-for-all with people punching each other outside in the street.

At the time, were you already living in the suburbs?

Y. T.: Yes, in this same area. For some reason, I didn’t like public transport, so I’d go to Shinjuku or to work by taxi. I guess most of my salary was spent on transport, eating out, and fashion (laughs). But I liked it that way. When I think back to those years, it was like heaven and hell – all mixed up together. Tokyo might have been on fire, but many people didn’t really worry about the future. There was a lot of optimism and incredible energy. It was what you could call a movement, a cohesive creative scene. After 1970, the mood changed considerably; everybody went their own way, pursuing their own projects, but in those short years between 1967 and 1969, it seemed that everybody was working with everybody else. I doubt those times will ever return.

INTERVIEW BY JEAN DEROME