The current Imperial Palace in the centre of Tokyo has a long and turbulent history.

A lot of literature about Tokyo is fond of pointing out that the city centre, which was previously occupied by Edo Castle, is a void – a vast area where people are not allowed and underneath which even the subway trains cannot run. This is only partly true because though a good bit of the Imperial Palace grounds is off-limits, some areas – the East and Kitanomaru gardens – are open to the public and there is even a small part of the Imperial Palace grounds that can be visited free of charge (more about this later).

For centuries, this huge place (with a total area of 2.30 square kilometres) was the seat of political power in Japan. In particular, during the Edo period while the Imperial Court was in Kyoto, it was here, in the heart of the city that used to be called Edo, that all the political decisions were made by the Tokugawa clan and the shogunate (hereditary military dictatorship) government.

The music is only one of the many things that make Kogane-yu different. For one thing, the typical sento’s old, musty image gives way to an exposed concrete structure and an open-plan lobby in the middle of which, like an island, stands a front desk that seems more fitting for a bar. My first impression is actually not far from the truth because the guy behind the counter both serves drinks (Kogane-yu’s original craft beer and homemade non-alcoholic drinks) and mans the DJ booth.

Today, a visit to the Imperial Palace can hardly convey the look and atmosphere of the original place and the kind of activity that went on in and around the Tokugawa stronghold. The precursor to Edo Castle was built on the eastern edge of the Kojimachi plateau in 1457 by Ota Dokan, a military commander whose clan descended from the Minamoto family. Though much smaller than Ieyasu’s castle, it was a three-tiered structure surrounded by moats whose different parts were connected by gates and bridges.

After Dokan was killed in a rebellion in 1486, the castle changed hands a few times. Then, in 1590, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who was Japan’s de facto ruler at the time, conquered Odawara (some 80 kilometres south of Tokyo) on his way to defeat the Hojo clan, and on 30 August of the same year, Ieyasu, his junior ally, moved from his headquarters in Sunpu (now Shizuoka City) to Edo.

After Dokan was killed in a rebellion in 1486, the castle changed hands a few times. Then, in 1590, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who was Japan’s de facto ruler at the time, conquered Odawara (some 80 kilometres south of Tokyo) on his way to defeat the Hojo clan, and on 30 August of the same year, Ieyasu, his junior ally, moved from his headquarters in Sunpu (now Shizuoka City) to Edo.

According to a popular story, when the future shogun (military dictator) arrived, he found that Dokan’s old castle had fallen into disrepair. As for the rest of Edo, it amounted to 100 houses with thatched roofs. The lowland to the east of the castle was covered by grass and was much smaller than today – the equivalent of fewer than ten city blocks – since it ended abruptly at the seashore. On the southwest side, a plateau stretched as far as the eye could see towards Musashino while to the south of the castle was Hibiya Cove, part of what is now Tokyo Bay. In the beginning, the cove was used as a commercial port, but in the 1620s surplus soil from construction was used for land reclamation and the area became a district for daimyo (feudal lord) residences. Today, the moats to the southeast of the Imperial Palace are said to be remnants of Hibiya Cove.

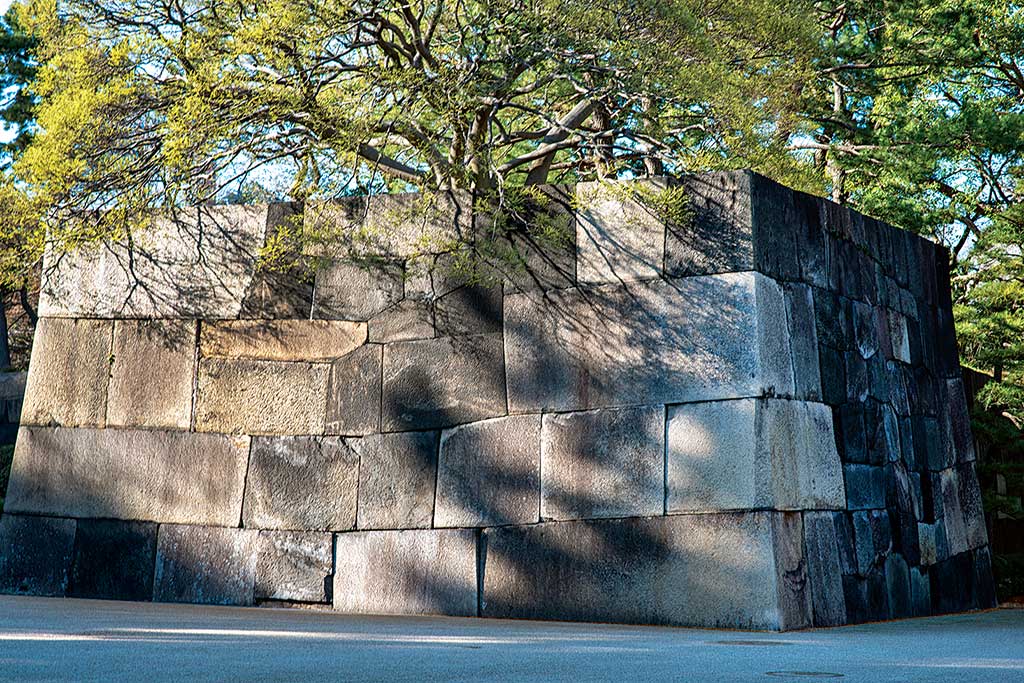

Ieyasu did not waste time in starting a colossal construction programme, which in 40 years turned Edo Castle into a citadel. In 1606, he had stone transported from various feudal domains to expand the building. In the following year, some daimyo were ordered to repair the castle tower and stone walls. In the end, 800,000 stones were gathered from around Japan, 200,000 of which were used to build the stone walls of the castle towers. The prized stone from Izu was particularly important in the construction of Edo Castle. Almost all of the stone for the magnificent walls was transported by ship from the western side of the Izu Peninsula, located more than 100 kilometres south of Edo. In 1614, Ieyasu announced the Siege of Osaka to complete the destruction of the rival Toyotomi clan, and all the daimyo, with few exceptions, were forced to participate. For this reason, after the end of an exhausting campaign, construction work was interrupted for three years. In 1618, however, the project was resumed and further expanded to encompass an even grander design. In 1636, for instance, a total of 120 families, including 62 daimyo in charge of the stone walls and 58 in charge of the moat, excavated the area from Iidabashi to Yotsuya and Akasaka, in what is now central Tokyo. When the project was over, Edo Castle had become the largest fortress in Japan, and for about 260 years, it was the site of the shogunate government, the place where fifteen Tokugawa shogun and their vassals conducted their affairs.

Alas, this Herculean effort came to nothing when, in 1657, much of the castle structure including the keep was destroyed by the Great Fire of Meireki, which lasted for three days, destroyed 60-70% of the city and is estimated to have killed over 100,000 people. That was not the only disaster to strike the place. Indeed, parts of the castle were repeatedly destroyed either by fires or earthquakes and rebuilt over the years.

The castle was a complex, maze-like structure comprising 25 outer walls, 11 inner walls and 87 buildings. Among them, Honmaru Palace played a central role as the residence of the shogun and the nerve centre of the Tokugawa bureaucracy. Divided into three parts, the front was the shogun’s audience room and housed offices of various government officials; the middle was the shogun’s living space; and the inner part – the fabled Ooku – was where the noblewomen lived. A sort of Japanese-style harem, it was the residence of the shogun’s official wife and her children, the shogun’s concubines and their children, the past shogun’s official widow, and his widowed concubines – each party, of course, occupying different quarters. The Ooku was connected to the rest of the Honmaru by a single corridor (later two) that was usually locked. In fact, the women living inside could not leave the castle nor could male adults be admitted inside the Ooku without the permission of the shogun.

A complex bureaucratic machine was assembled to keep the country under control, and an army of officials commuted to work every day from their residences around Edo Castle. Among them were the roju (senior councillors) who served as assistants to the shogun and the young toshiyori (lower-ranking officials). Then there were the metsuke (inspectors who were charged with the special duty of detecting and investigating instances of maladministration, corruption or disaffection), the magistrates, the pages and so on. The roju, for instance, worked from 10:00 to 14:00. The magistrates, on the other hand, were much busier as their job was the equivalent of today’s governor of Tokyo, superintendent of the police, chief of the Tokyo District Court, chief of the Tokyo Fire Department, and chief of the Tokyo National Highway Management Office all rolled into one. The time they spent at Edo Castle was the same as the roju but after that they would return to their respective magistrate offices to file lawsuits and petitions, and investigate criminals, typically working until after midnight. Last but not least, a place such as Edo Castle needed a lot of guards. Called bangata, they worked in three shifts. All in all, it is estimated that about 6,000 people were in Edo Castle during the day, including 5,000 men with different occupations and 1,000 women inside the Ooku.

The Tokugawa rule lasted until 1868. During the first part of the Boshin War (1868-69) fought between the shogunate forces and a group of rebel daimyo seeking to seize political power in the name of the emperor, the imperial forces lay siege to Edo Castle and only a last-minute meeting between Katsu Kaishu, the former head of the army of the shogunate, who was entrusted with full negotiating power, and Saigo Takamori, then leader of the Imperial Army, spared the castle from an all-out attack and ensured its bloodless surrender.

However, that did not mean that the place was safe from other disasters: in 1873, Nishinomaru Palace, which by now was used as the Imperial Palace, was destroyed by fire and was replaced in 1888 by the newly built Meiji Palace. Finally, on 1 September 1923, the remaining structures of the old castle were severely damaged by the Great Kanto Earthquake and many of them were not restored.

Even Meiji Palace did not last long: during an American air raid on 25 May 1945, the General Staff Headquarters along the Sakurada moat (where the Constitutional Museum is currently located) was bombed and burned to the ground, causing sparks to ignite Meiji Palace, which also burned down. 19 members of the Metropolitan Police Department’s special fire brigade were killed while trying to extinguish the fire. However, Emperor Hirohito and other people took refuge in the Imperial Library in the Fukiage Gardens and were safe.

The emperor used the library as a temporary palace, and for some time after the war, the Imperial Palace was not rebuilt. Irie Sukemasa, who served as the emperor’s chief chamberlain, later wrote in his book that the emperor thought the reconstruction following the war damage and the accompanying improvement of people’s lives should be given top priority, so it was not possible to immediately rebuild the palace. Finally, in 1968, the current Imperial Palace was built on the site of the old Meiji Palace.

Though today the palace grounds look very different from Ieyasu’s times, the place is still very much worth a visit. Even from the outside, for instance, we can admire Fujimi-yagura, one of Edo Castle’s old keeps. All the keeps were destroyed during the Great Kanto Earthquake, and only this one was restored.

Visitors to the East Gardens enter through the Otemon Gate (the main gate) which is open from 9:00 to late afternoon (between 16:00 and 18:00, depending on the season).

In the Edo period, imperial envoys, generals and daimyo often entered and exited the castle through this gate, and the security was extremely strict. After being destroyed in the Great Kanto Earthquake, the interior was initially rebuilt in concrete, but was later restored to the original wooden structure.

Another of the few buildings that still survives in its original form is the Hyakunin Bansho (100-people guardhouse), a low structure that used to protect the paths leading to the Honmaru and Ninomaru. It was filled by an elite 100-man-strong military unit whose members had a direct connection to the Tokugawa family and included the Koga group, also known as Koga ninja, and the Twenty-Five Horsemen.

The Hyakunin Bansho was an important checkpoint and only members of the Owari, Kishu, and Mito families of the Tokugawa clan were allowed to pass through it while riding on palanquins or on horseback. All the other daimyo had to dismount and undergo inspection, and their attendants would often wait here for their master’s return.

Somewhere that should not be missed is the Ninomaru Garden, which has been restored based on the drawings of the 9th shogun, Tokugawa Ieshige. The garden features 260 trees from each of Japan’s 47 prefectures and is planted with 84 varieties of Japanese irises, which were inherited from the Meiji Jingu Shrine in 1966.

Unfortunately, what should have been – in every way – the high point of the visit, the pièce de résistance, is the castle tower, which is missing. At 45 metres high, it was the country’s tallest – its stone base alone was 14 metres high. As a comparison, the Osaka Castle and Himeji Castle towers are only 30 and 31 metres high. As mentioned earlier, the Edo Castle tower was destroyed in the Great Fire of Meireki in 1657 and was never rebuilt, partly due to economic reasons, partly because in a period of prolonged peace, it had become redundant. Therefore, the Fujimi-yagura watchtower was treated as a de facto castle tower. The stone base that we can see and even climb today was actually built one year after the fire and, at 11 metres high, is slightly shorter than the original one.

The non-profit Rebuilding Edo Castle Association was founded in 2004 to promote a historically correct reconstruction of the tower. In March 2013 Kotake Naotaka, head of the group, said that “Japan’s capital needs a symbolic building” and that the group planned to collect donations and signatures on a petition in support of the project. A reconstruction blueprint was drawn up based on old documents, but the Imperial Household Agency has not indicated whether it will support the project.

As mentioned at the beginning of this story, even the Imperial Palace grounds can be visited free of charge. Tours are conducted twice a day, at 10:00 and 13:30, and those who wish to join the tour can register either in advance or on the spot, both on a first-come, first-served basis – which means that you will need to register well in advance or start queueing in front of the palace very early if you hope to secure a place. The tours are conducted every day except on national holidays (excluding Saturdays), Sundays, Mondays and between 28th December and 4th January.

One of the spots visitors get to see is the Chowaden, a 163-metre-long building that is used for receptions and audiences. Most famously, the emperor addresses the people who assemble in the plaza in front of the building on 2nd January and 23rd February (Emperor Naruhito’s birthday). On that occasion, members of the imperial family appear before the public, standing behind bulletproof glass on the veranda of the Chowaden.

Gianni Simone