The trees clothed in their autumn colours are a stunning spectacle that’s not to be missed.

The trees clothed in their autumn colours are a stunning spectacle that’s not to be missed.

There’s something magical about the onset of autumn in Hiroshima. Summer’s suffocating heat is just a memory; the typhoon season has blown itself out, leaving bright days and refreshingly cool nights. The rice harvest is in full swing and joyous harvest festivals are held in celebration.

At Shinto shrines in town and countryside, colourful Kagura plays are performed, re-enacting ancient myths of slaying demons and appeasing the gods. But the season’s crowning glory is koyo: the spectacular colours of autumn leaves, and Hiroshima’s location – sandwiched between the Chugoku Mountains and the Seto Inland Sea – means there’s an abundance of koyo-viewing opportunities. City gardens, romantic islands and misty mountains are transformed by the autumn colour of maple, ginkgo, rowan, beech, chestnut and cherry into a blazing wonderland of red and gold. In Japan koyo inspires a reverence that borders on the spiritual. For a few brief weeks, momiji-gari (maple leaf hunts) become a national obsession, and no one can resist this annual call of the wild.

By early October, signs of koyo fever are everywhere. Shops are festooned with colourful fake maple branches and TV weather forecasts give regular updates on the leaves’ colour. At train stations, Momiji Diary posters chart the trees’ progress from green to red, region by region. At work, it becomes the main topic of conversation around the office coffee machine. The beer giant Kirin even produces a “Specially Limited Autumn Brew” every year, in cans emblazoned with – what else? – maple leaves. In the crisp cold air of the mountains that girdle Hiroshima, koyo starts a couple of weeks ahead of the lowlands. At this time, thousands of Hiroshima residents make the pilgrimage to Sandankyo Gorge, an Outstanding Scenic Beauty Spot about 70km north-west of Hiroshima city. One of the five most famous ravines in Japan, Sandankyo is renowned for its waterfalls and stunning autumn colours, the crimson maples and golden ginkgos contrasting with the emerald pines and cedars. For many Westerners, autumn conjures wistful images of solitary strolls and melancholy moods, but in Japan solitude is not on the agenda. At peak viewing times, the narrow footpath through the 16-km Sandankyo ravine becomes a human conveyorbelt: sprightly 70-somethings with bells, walking sticks and sensible clothing; salarymen in designer sportswear; young girls in mini-skirts, high heels and Vuitton backpacks. The whole world is here. If you tire of the crowds though, why not relax on one of the riverboats that run through the ravine? At one point, known as Sarutobi, the passage between the moss-covered canyon walls is just two metres wide.

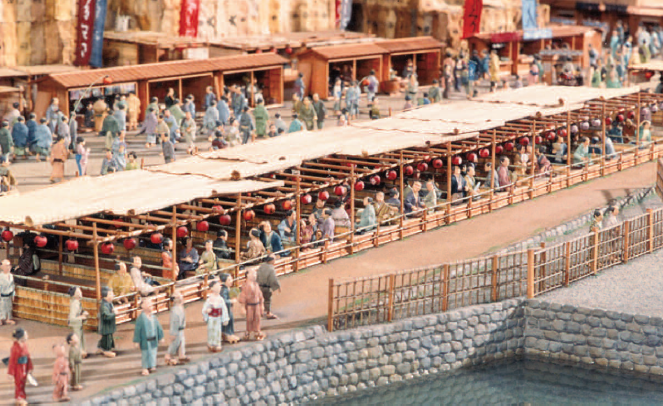

Momiji-gari has been popular in Japan for centuries. According to Shinto belief, mountains and forests are sacred places inhabited by deities, and so mass pilgrimages to the country to observe the changing foliage were therefore a spiritual act, a way of communing with the gods. Maple-viewing is still a collective activity, but unlike the hanami of cherry-blossom time, there are no boozy parties and the atmosphere is sedate rather than euphoric. People come to walk and watch, and, as was seen at the World Cup in Brazil, they take their rubbish home with them. Back down at sea level, it’s time to board the ferry to the sacred island of Miyajima, perhaps the place held dearest in the hearts of Hiroshima’s people.

Just a ten-minute ride across the bay, Miyajima is renowned for it’s great vermillion torii, or gateway, rising out of the sea. Miyajima is one of Japan’s Top 3 Beauty Spots, and the magical Itsukushima Shrine, floating on the sea against the velvet backdrop of Mt. Misen’s primeval forest, deserves a place on anyone’s bucket list.

However, come autumn, the place to be is Miyajima’s Momiji-dani Park – a maple woodland cultivated during the Edo period at the foot of Mt. Misen. Today it is home to 200 maple trees, herds of semi-tame deer and crystalline streams spanned by delicate orange bridges. No matter how crowded it gets, the enchanting spell endures. Maples are such an integral part of Miyajima that its most beloved product is Momiji Manju, a mapleleaf-shaped cake filled with bean paste, chocolate or custard. Mountains and forests aside, the next best place to enjoy koyo is a traditional Japanese garden. Shukkeien, in the heart of downtown Hiroshima, was originally built in 1620 as a garden for daimyo (feudal ruler) Asano Nagaakira by Ueda Soko, a warrior who became a Buddhist monk, teamaster and landscape gardener. As Steve Jobs remarked about similar gardens he visited in Tokyo “it’s the most sublime thing I’ve ever seen”. Shukkeien is a miniaturized version of the landscape at Lake Xi-hu in Hangzhou, China, in a space of just 40,000 square metres. In its centre lies the large Takuei pond, with its striking hump-backed Rainbow Bridge. Around it, winding paths lead you through miniature mountains, valleys, rice fields, bamboo groves and tea plantations. This garden is ideal for losing yourself along little side trails among the isolated nooks, waterfalls and lichen-covered stone lanterns. In autumn, sheltering in one of the half-hidden rustic arbors, with raindrops glistening on the moss, it’s easy to pretend you’re 17th century haiku master Matsuo Basho, composing seventeen syllable odes to the chattering frogs. Alternatively you can attend a maple-viewing tea ceremony in the beautiful Seifukan tea-house, with its thatched roof and lyre-shaped window. I feel that there is still hope for the world as long as people can take time out to have a cup of tea and contemplate the wonderful foliage.

Hidden away on the south side of town lies Hiroshima’s second most beautiful garden: the Hanbe Garden restaurant, onsen (hot bath) and ryokan (guest house) complex. Hanbe is enormously popular for weddings, chiefly because its gorgeous garden makes such a photogenic backdrop. So you’re likely to encounter brides and grooms there in sumptuous kimono, with camera crew in tow. The restaurant looks out onto the traditional Japanese garden – waterfalls, carp ponds, islands, bridges, pines – and then stretches up a steep hillside covered in maples (over 1,000 of them). Take the short hike up the hill and you will find yourself virtually alone. You might even spot a tanuki (Japanese badger) grumbling through the azaleas. Fancy something more spiritual? Hiroshima’s got that too. Just one Astram Line station away from the bustling downtown shopping precinct of Hondori lies the peaceful grounds of Fudoin Temple.

It’s the only temple to have survived the bomb, and the largest remaining medieval Kara-style kondo (Golden Hall) in Japan. Built around 1540, the kondo is Hiroshima city’s only designated National Treasure. The juxtaposition of the elegant temple, the orange pagoda and the maple trees skirting the little carp pond, the air sweet with incense, makes for a delightfully serene setting. Talking of temples, for an experience that verges on the mystical, don’t leave Hiroshima without visiting Mitaki. It’s only two stops from Hiroshima station on the Kabe line, but it feels like you’ve entered another world. The temple, which dates from 809, stands near the top of Mt Mitaki. The entire hillside is covered in dense forest, made lush by the three waterfalls that give Mitaki its name (Mitaki literally means “three waterfalls”). The path up to the temple is lined with hundreds of statues: larger than life bodhisattvas, many-armed, elephant-headed Buddhas and tiny red-hatted jizo.

In the autumn, 500 maple trees cast a red glow over the forest, filtering the sunlight like stained-glass windows. At the bottom of the hill you’ll find the charming Kutenan teahouse overlooking a carp pond and surrounded by maples, ideal for unwinding over some frothy macha tea and warabi mochi. Expect crowds at Mitaki too, but as at Sandankyo and elsewhere, the atmosphere is quietly cheery, with strangers bonded by the desire to catch Nature’s last great performance of the year before

it shuts down for winter.

Steve John Powell

Photo: Angeles Marin Cabello