Just like the Siena Palio, Fukushima prefecture’s Soma Nomaoi is an event where riders can represent their region with pride.

Just like the Siena Palio, Fukushima prefecture’s Soma Nomaoi is an event where riders can represent their region with pride.

The sun is rising over the Nakamura Shrine and Ito Kazuhiko is hard at work in the stables where he is preparing his horse for the annual Soma Nomaoi races. With velvet pompoms, a black and gold leather saddle blanket and black lacquered stirrups, nothing is too extravagant for this event that celebrates 1,000 years of the history of the Soma samurai clan and the city of the same name in Fukushima Prefecture. Translated literally as the Soma wild horse chase, the origins of the Nomaoi date back to the Sengoku era (mid 15th century – end 16th century) when samurai would train secretly by capturing herds of wild horses as offerings to the Shinto gods. “If you’ve seen the movie The Last Samurai, you know that those men were part of clan Soma!” Kazuhiko exclaims with pride as he strokes his horse’s rump. A native of the port city of Soma, he’s 31 years old and is riding at the great Shinki Sodatsuen race course for the first time.

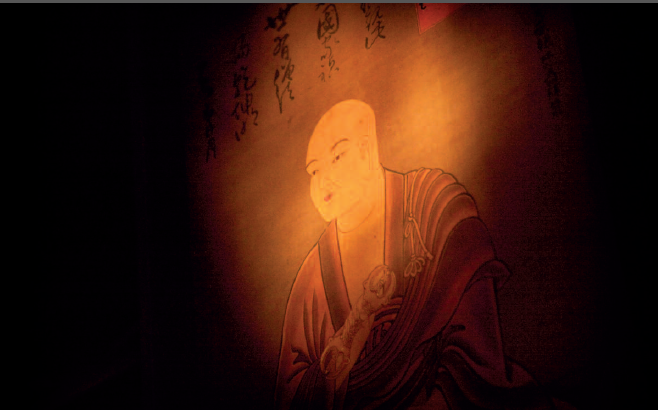

He been training for this event for over 10 years. Far in the distance the cicadas begin their song as the sun rises. Soon the heat will be unbearable, but for the time being, the shrine is still a sanctuary of peace where the riders can bond with their steads far away from the crowd. “We have prayed to the gods of the shrine to ensure that this festival will recapture all its former splendour, and to ensure that Soma recovers quickly,” explains Takahashi Makoto, who oversees the Nomaoi in the neighbouring city of Minami- Soma. The triple disaster on the 11th of March 2011 has left permanent scars across this coastal region, whose livelihood used to be fishing. The nuclear accident at Fukushima Dai-ichi, only 20km from here, forced 160,000 residents to leave the nearby villages, which were designated as exclusions zones. Many have found refuge in Soma and Minami-Soma and still live in temporary housing there. However, even in 2011, the local people did not miss out on celebrating this colourful annual event. Starting the day before with a procession of riders in Soma, the festival attracts hundreds of people from early morning. The growing crowd then heads for the Ota Shrine in Minami-Soma for the start of another procession. The Nomaoi festival recreates three samurai warrior rituals over a period of three days and takes place around the three local shrines of Nakamura, Ota and Odaka. In this splendid landscape of rice-fields surrounded by mountains, the cavalcade solemnly advances to the rhythm of drums and conch horns, what could be a perfect replica of a painting from the Middle Ages. Behind the commander-in-chief, monks, palanquin bearers, grooms and warriors, but also children dressed up as princes, all parade in an atmosphere both majestic and calm. The riders astride their proud mounts wave and laugh with the onlookers who gather alongside the rice-fields, fanning themselves as they curse the heat. Like all matsuri – traditional Japanese festivals – Nomaoi is an event when family and friends come together. For some, it’s also the opportunity to express their passion for horses.

“I’ve come from the town of Fukushima, I love horse riding and it’s the first time I will be part of the Nomaoi this year,” a young woman entrusted with keeping the riders to a walking pace reveals emotionally. Some horses whinny and pull, unnerved by the crowd and the slow pace of the procession. In days gone by, horses from Soma were renowned across the whole of Japan, but today another stronger, taller breed is favoured. “We had to adapt our horses to the height of Japanese people today. Our ancestors were no taller than five foot three!” Kazuhiko explains. He bought his horse 6 months ago, just in time to start its training. “The Nomaoi is a special festival. You can’t take part just because you want to, you need to find the right horse, and it’s not like a car, it requires more than money!” he tells us. Unfortunately, as he arrives at the Hibarigahara festival site where the first Nomaoi race is to take place, Kazuhiko has a bad fall from his horse. He’s taken by ambulance to hospital. The injury is not serious, but the doctor prefers to keep him in for observation. Later we head back without him to Mihosushi, the restaurant his parents run in Soma, which is a veritable little museum dedicated to the Nomaoi. Ichiko, his mother, smiles as she serves tempura and sashimi dishes as we sit on tatami waiting for her son. “A few years ago, I started researching my ancestors and where they came from, and I discovered that they were samurai. That’s why Kazuhiko decided to enter the Nomaoi. You need to wear the samurai insignia of your family to be able to enter,” she explains as she shows us the Ito coat-of-arms, a gentian flower, in pride-of-place above a display of a dozen sake bottles, gifts from family and friends. Kazuhiko soon returns with two of his most loyal friends. In a gloomy mood after his fall, he eats a little before going upstairs to his apartment to have a rest, and declares he will still enter the big race the next day. His family make no comment. Kazuhiko has been training for six months, leaving work after midnight to practise racing with his horse. The family has been through much worse however. The restaurant, which is also their home, was half destroyed by the earthquake, while Kazuhiko’s sister-in-law who’s from Namie – 3 kilometres from the damaged nuclear power plant – is now a refugee.

Finally, friend of the family Tadano Aiko, who was a worker at the power station, lost her mother and sister in the tsunami. For the Ito family, their son entering the Nomoai race for the first time is about safeguarding a tradition. There’s only a handful of young riders, including Kazuhiko, among the 500 who take part in this festival, which has been designated as part of Japan’s Important Intangible Folk Heritage. At 10am the next day the Ito family are gathered outside on their parking lot in the scorching summer heat and are hard at work fixing 30kg of armour onto Kazuhiko’s strong frame. The equipment is impressive: gauntlets, greaves, cuirass, coat of chain-mail, leather, wool and silk, all patched up lovingly by his mother. “We bought everything in Kyoto, but it was in such a poor state! Some of these pieces of armour date back to the Momoyama wars before the Edo era!” Ichiko tells us as she ties the white scarf over her son’s forehead. “Japanese armour is different from European armour, it doesn’t cover the whole body, only the most sensitive areas, like the heart, neck, and thighs, because the code of honour dictates that you fight face to face, never attack from behind,” adds Kazuhiko. All around them, other families are taking part in the same rituals, surrounding their sons, husbands or brothers who will be representing their ancestors today. “There are still a lot of people who use their greatgreat- grand parents’ armour that they have been lucky enough to keep,” Kazuhiko says as he puts on his helmet made of wild-boar hair and decorated with horns. At last he’s ready and, weighted down, he makes his way towards the petrol station that has been transformed into a medieval stable, with horses walking by the petrol pumps and a line of warriors sitting calmly, their sabres – katana – by their sides as they wait for the procession to start. It’s 3km to the Hibarigaha festival site where the big race will take place. “Careful, stand back!” the loudspeakers call out as the procession approaches. The city is now one vast traffic jam, everyone trying to make it to the stadium as quickly as possible. We accompany the Ito family onto the large grassy area in the centre of the stadium, which serves as a backdrop. Sitting on the grass, families are just finishing up lunch, huddling as best they can under parasols while some of the riders smoke a cigarette before the race. The thousands of spectators sitting all around us in the stadium are all wearing hats to protect them from the sun “Don’t forget to drink! Don’t forget to drink!” the speakers declare. Soon people on the steps start to call out to the first riders of the race with all the force the Japanese language can muster. Advancing two by two, the samurai try to keep their neighing mounts in check as best they can as the starting pistol is fired. They have a thousand metres to cover, quite a long distance if you consider the blazing July heat with temperatures close to 45°C.

A horse suddenly becomes faint and almost keels over as it is taken to the caravan that serves as a first aid station. A woman dabs his forehead with ice while two elderly men force him to swallow salt. “It’s to make him drink! Horses can die from sunstroke in this terrible heat!” one of them tells us. The festival was traditionally held on the 25th, 26th and 27th of May before it was brought forward gradually to the end of July. “In the past, we were all farmers and the festival respected the Shinto calendar for rice planting. Nowadays, most of us are ordinary company employees and have slowly abandoned the religious aspect of the Nomaoi, so it’s become a summer weekend event,” an old man explains. Every year, some horses die from the heat, but there’s no doubt that the date being set in the summer means the Nomaoi attracts more tourists. This is an economic advantage that has a major impact, claims Takahashi Makoto. He explains that with the help of the new motorway linking the city of Iwaki to Soma, the Nomaoi can welcome up to 210,000 visitors from across the whole of Japan. The race is coming to an end and, far off on the race course, Kazuhiko is turning his horse as if he’s reining it in. He hasn’t won this race, but there is still one last competition, and it’s the most important: the Hatatori. Forty flags have to be caught from the air while racing at top speed. With the sound of crackling fireworks, the flags are shot skywards one by one, followed by forty samurai racing to catch one. All of a sudden, the samurai are no longer solemn and calm, but a horde of warriors shouting and cursing each other, ready to grab and push each other as the flags fly through the air. As the conch sounds for the last time, marking the end of the festival, Kazuhiko throws himself into the fray and catches a flag at the last moment. Joyfully, he heads to the grandstand to receive the judges’ congratulations. But for him, nothing is worth more than what he holds in his hands. “This is the most beautiful gift I could give to my wife, who’s expecting, and to my ancestors. I am the youngest in the history of my family to have caught a flag!” he exclaims as he holds close the flag from Nakamura Shrine, from his beloved city of Soma.

Alissa Descotes-Toyosaki

How To Get There

From Tokyo, take the Tohoku shinkansen to Sendai, taking about two hours. Then change to the Joban line to Haranomachi, 100km to the south. Finally, there is a free shuttle service to the different sites of the festival. The 2016 festival takes place between the 30th of July and the 1st of August.

Photo by Jérémie Souteyrat