Designated as a Unesco World Heritage site in 2004, Mount Koya, an important Buddhist shrine, holds many surprises.

Designated as a Unesco World Heritage site in 2004, Mount Koya, an important Buddhist shrine, holds many surprises.

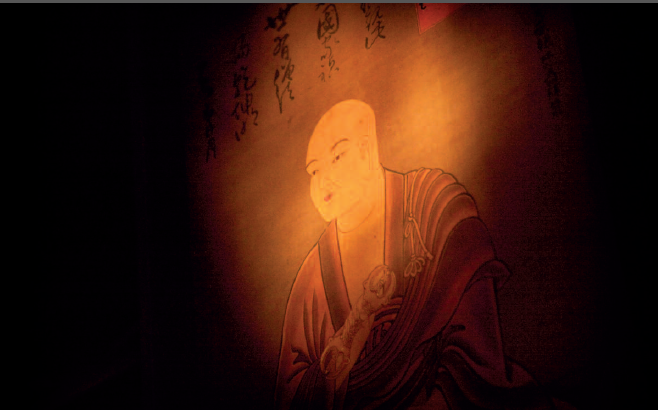

This place is often neglected by foreign tourists who prefer to visit Kyoto or Nara. Yet Mount Koya, or Koya-san to the iniated, is an amazing location that deserves a visit. Getting there is not very difficult at all and takes around two and a half hours from Osaka, Kyoto or Nara. The mountain temple complex is unique and captivating, especially if you visit at a time when the mist appears through the trees, the temples and other sanctuaries. It is a very mystical place that seduced the monk Kukai (renamed Kobodaishi after his death) nearly 1,200 years ago on his way back from China, where he studied Chanyang’s tantric doctrine. The legend says that it was the Shinto divinities that led him to this hard-to-access mountain, at a height of 1,000 meters. Having convinced the Emperor to give him the right to create a hermitage, the monk founded the Kongobu-ji temple here in 832, the first temple in which he preached his Shingon doctrine, adapted from what he had studied on the continent. It’s sphere of influence extended over the entire area of Koya-san as well. The temple that currently bears the name (open from 8.30am – 5pm, entry is 500 yen) is more recent, but it is still the principal monastery of Shingon Buddhism. Within its precinct shelters the biggest stone garden in Japan, the Banryu-tei, with rocks evoking mountains rising above a sea of clouds. The oldest building still standing on Mount Koya is the Fudo-do, dating back to 1197 and it escaped many fires that destroyed most of the other temples. Classified as a national treasure, the Fudo-do doesn’t possess the majesty of the other buildings, but it exudes a serenity that few can resist. It is situated on the Danjo Garan site, which is made up of five elements including the main gateway (Daimon). Placed at the entrance to the complex, the Daimon is a building 25 metres high, flanked on either side by the figures of two divinities, whose mission is to protect Koya-san.

Many tourists stop for the view of the inland sea and amateur photographers appreciate the mountain’s spectacular sunsets. They also like to stop outside the Daito, the big pagoda (8.30am – 5pm, entry is 200 yen) that was built by brother Kukai as a central element of the monastic complex. The original building was built in 816 over a period of 70 years, but alas it did not survive the fires. The current pagoda actually dates back to 1937. It measures 49 metres in height and shelters a statue of the Mahavairocana Buddha, with four Buddhas and sixteen bodhisattvas painted on the pillars. The way they are positioned actually forms a three-dimensional expression of an important mandala (symbolic images to aid meditation) in Shingon Buddhism. This Buddhist sect claims to have twelve million followers and professes a doctrine according to which anyone can aspire to enlightenment and becoming a Buddha, reaching Nirvana through the untiring repetition of mantras (incantations) and the visualisation of mandalas. Opposite the Great Pagoda, you can visit the Golden Pavilion (Kondo, 8.30am – 5pm, entry is 200 yen), where the main Buddhist services take place. Initially built in 819, the current structure dates back to 1932.

Right next to it is the latest addition to the Danjo Garan site, the Mie-do or “portrait pavilion”. This building is not accessible to the public but it still holds some importance, as it is where the monk Kukai is said to have lived. Inside is a portrait of Kukai himself, said to be painted by his disciple, the imperial prince Shinnyo. The building is opened once a year, on the eve of the 21st of March, the anniversary of the date when Kukai is meant to have entered meditation for all eternity in 835 (the date of his death). To see his artwork from Mount Koya’s various monasteries, we recommend the Reiho-kan museum (8.30am – 5.30pm May to October and 8.30 am – 5pm November to April, entry is 600 yen) situated on the other side of the road that runs through the Danjo Garan. The building contains many major pieces of Buddhist art, most of which are classified as national treasures. The second essential place to visit in Koya-san is Oku-no-in, a temple complex that is particularly spellbinding on a foggy day. It is surrounded by an ancient cemetery and the 200,000 tombs, scattered over an area of two kilometres, are in the midst of a forest of hundred-year-old cedars, which make the place somewhat more unsettling.

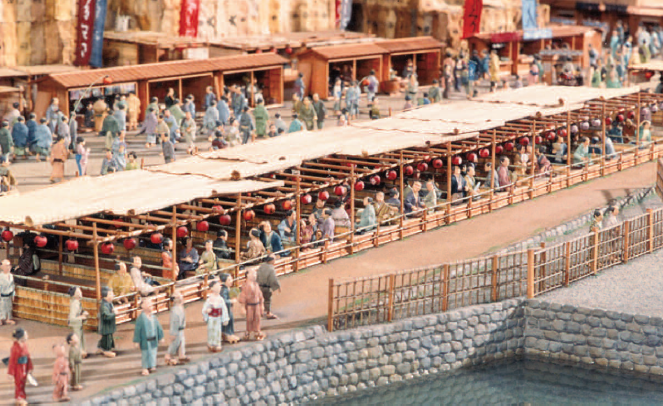

It is easy to understand why the Japanese are so fascinated by ghost stories when you find yourself in a place like this amongst thousands of tomb stones covered in moss. This sacred place, which begins at the Ichi no hashi bridge, is also notable for the diversity of the monuments it encloses. Amongst them is a rocket, part of a memorial by the Nissan Group in honour of their workers. The UCC society that specializes in selling coffee naturally chose to mark its presence here with two huge cups that many stop to stare at. Though these constructions catch the eye, most of the tombstones are quite simple.

There are many five story stone stupas with carvings of characters relating to the five elements of Buddhist cosmology (earth, water, fire, wind and void). In many strains of Buddhist doctrine, the Buddha Mahavairocana’s body as well as the human body and all of the physical world are made up of these five elements and they do not disintegrate after death. The most famous stone stupa is Ichiban sekito, which was built by Tokugawa Tadanaga, son of shogun Tokugawa Hidetda, in memory of his mother. It is 10 metres high and is the biggest in the necropolis. Along the path that leads to the Kobo daishi mausoleum there are little Buddhist statues wearing bibs. They are representations of the Jizo bodhisattva, which according to popular belief, takes care of children and looks after them in the next world. There are quite a few and many bear funny facial expressions.

A few dozen metres away from the mausoleum, the Gobyo no hashi bridge marks the entrance to the most sacred part of Oku-no-in. Here you will find the Pavilion of Lanterns (Toro-do), a prayer chapel that contains over 10,000 lanterns left by believers. On the other side is Kobo Daishi’s mausoleum, which according to tradition, is not the resting place for his corpse but houses the ever-living monk in a state of eternal meditation. That is why monks still serve him two meals a day. The mausoleum is the pilgrim’s last stop before reaching Mount Koya. Before the advent of public transport and the construction of roads suitable for cars, believers used to walk the pilgrim paths. There are seven in total (known as the Koya nankuchi), and the most famous is the Choishi-michi that is 24 km long. This path connects the Jison-in monastery in Kudyama to the main gateway (Daimon) that marks the entrance to Koya-san’s sacred site. It’s name comes from the stone markers every 109 m. Like all of Mount Koya, this road was given Unesco World Heritage status in 2004 and if you aren’t in a rush, it’s a beautiful walk. The path begins two kilometres from Kudoyama station and it will take you approximately 7 hours to walk to Danjo Garan.

To take advantage of the pilgrimage atmosphere you can spend a night in a monastery (shukubo). 52 of the 117 monasteries offer accommodation and vegetarian meals (shojin ryori). Originally, they provided housing for migrant monks. Nowadays, the rooms in many monasteries are comparable to the best hotels, with all the comfort you would expect. You can ask to join morning prayers around 6am and many tourists enjoy the experience, so we recommend you make a reservation (www.shukubo.net). Mount Koya is accessible in any season, however, the most impressive time is winter, when snow and mist give the area a mystical atmosphere that suits the monk Kukai’s Shingon Buddhism. There are also many small cafes to visit after this meditational walk. One of them, the Bon On Sha (0736 56 5535), right by the post office, is especially cosy. They serve delicious hot chocolate in warm gallery/ shop surroundings, filled with local handicrafts and photos of the region. Once you are reinvigorated, you can continue your trip to the many other sacred locations in the region.

Odaira Namihei

Photo: Jérémie Souteyrat