An expert on Japanese theatre, William Andrews offers his analysis of how it changed at the end of the 1960s.

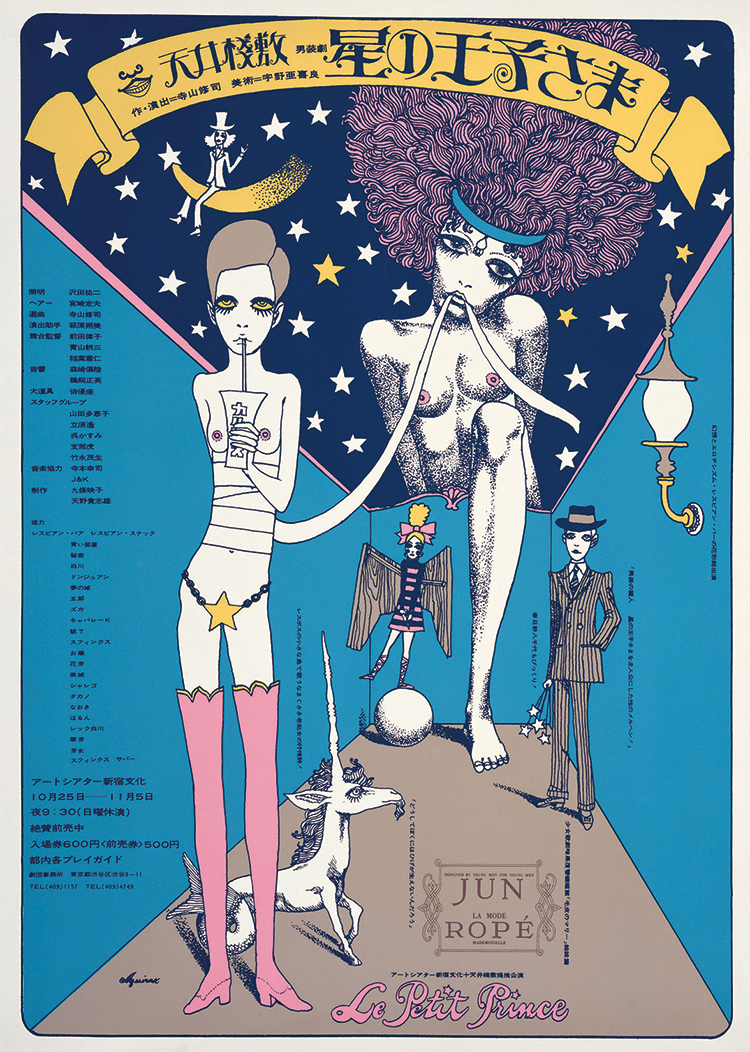

Poster of The Little Prince (Hoshi no Ojisama) played by Tenjo Sajiki troupe led by Terayama Shuji.

According to some observers and theatre insiders, Kyoto is the most exciting centre for contemporary theatre and the performing arts in Japan today. But there was a time, in the late 1960s, when Tokyo ruled the Japanese theatre world, and some of the most innovative, vibrant and challenging works were staged in Shinjuku.

I had a chance to talk about Japanese theatre’s past glory days with William Andrews, a Tokyo-based writer and translator who for several years has been a theatre insider in Japan. While Andrews doesn’t consider himself to be an expert, he has translated play scripts and other content for many leading contemporary Japanese artists. Besides providing information on contemporary Japanese theatre through his website (https://tokyostages.wordpress. com), he translates or writes for Festival/Tokyo and other Japanese performing arts events and art institutions. Andrews co-translated Tokyo Theatre Today: Conversations with Eight Emerging Theatre Artists (2011) with Iwaki Kyoko, and is currently working on a biography of film director and screenwriter Adachi Masao. His other areas of interest are social and political history, with a particular focus on Japanese radicalism, counterculture and protest movements (in 2016 he published the critically acclaimed Dissenting Japan: A History of Japanese Radicalism and Counterculture, from 1945 to Fukushima).

“The years between 1967 and 1969 were crucial for the development of underground and avantgarde Japanese theatre,” he says. “In 1968, for example, butoh’s prime mover Hijikata Tatsumi performed his solo dance Hijikata Tatsumi and Japanese People: Rebellion of the Body at Nihon Seinenkan which is in Shinjuku Ward, between Harajuku and Aoyama. This is one of the most important performances in butoh history. The title itself provides an extremely powerful image, especially considering what was going on at the time. Thousands of people were fighting in the streets, and here we have someone talking about the rebellion of the body. Does it mean ‘against the body’? or ‘with the body’? The title itself is rather ambiguous.”

A certain standard public image of butoh has become popular through the years (thin bald men with stark white bodies) as if it were a uniform movement. “In reality the butoh scene is quite diverse,” Andrews points out. “There are many women involved, to begin with, and there are a variety of styles. However, they all share this spiritual quality, and it all goes back to Hijikata and the postwar generation.” Much closer to Shinjuku Station, a strange Red Tent used to stand within the grounds of Hanazono Shrine. “That was where Kara Juro and his troupe, Situation Theatre, were performing,” Andrews says. “He had pitched the Red Tent one year before, in 1967, with the shrine’s permission. It was even featured in Oshima Nagisa’s Diary of a Shinjuku Thief.”

In the late 60s a visit to the Red Tent was a must for many theatre fans. A few years later they stopped performing for a while, after the shrine received complaints from the local retail association that didn’t like the kind of grotesque and “profane performances” (involving lots of nudity and sexuality), which were being performed inside what were supposed to be sacred grounds. “However, they resumed performing after a while,” Andrews says. “Now, I think they usually do it about once a year. I guess, eventually, even avant-garde culture becomes mainstream and is co-opted by the commercial system.” Kara and other underground playwrights liked to write stories about humble people, not historical heroes. Indeed, many of their characters are often of low or ambiguous social status. “Kara, in particular, liked historical rebels,” Andrews says, “but even Sato Makoto – who in the same period was performing elsewhere, inside his Black Tent – had a play about Nezumi Kozo, a famous Edo-period thief and folk hero. In other words, these playwrights tackled contemporary issues while looking back at the past for inspiration.

“It’s interesting to compare this period with the present situation because now everybody seems to be obsessed with ‘black boxes’ (cultural spaces, public halls, etc.). In the 1960s they would just travel around with a tent ,which, by the way, was a practice that went all the way back to the Edo period (1603- 1867). If you see Diary of a Shinjuku Thief you can appreciate Kara’s brand of street theatre.” Another charismatic figure in those years, Terayama Shuji, went beyond street theatre. In his more experimental works, he practised what was called shigaigeki or “city theatre” as his performances took over whole city districts. In 1970, for example, he used Shinjuku as his stage when he produced Solomon: The Human-Powered Airplane. The performance was conceived like a trip, and the audience had to buy an airline-style ticket (or, in certain cases, got one free). “You have to remember that in 1970 very few Japanese could afford to travel abroad,” Andrews says, “so Terayama was offering people a chance to “fly” and have an exotic experience.”

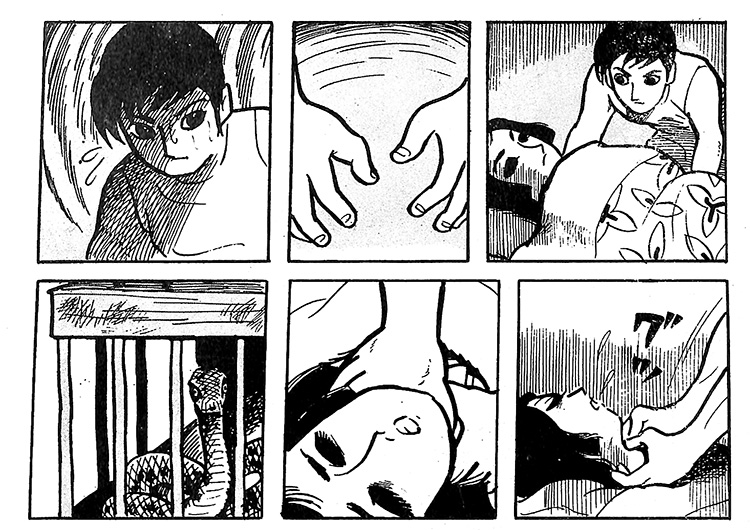

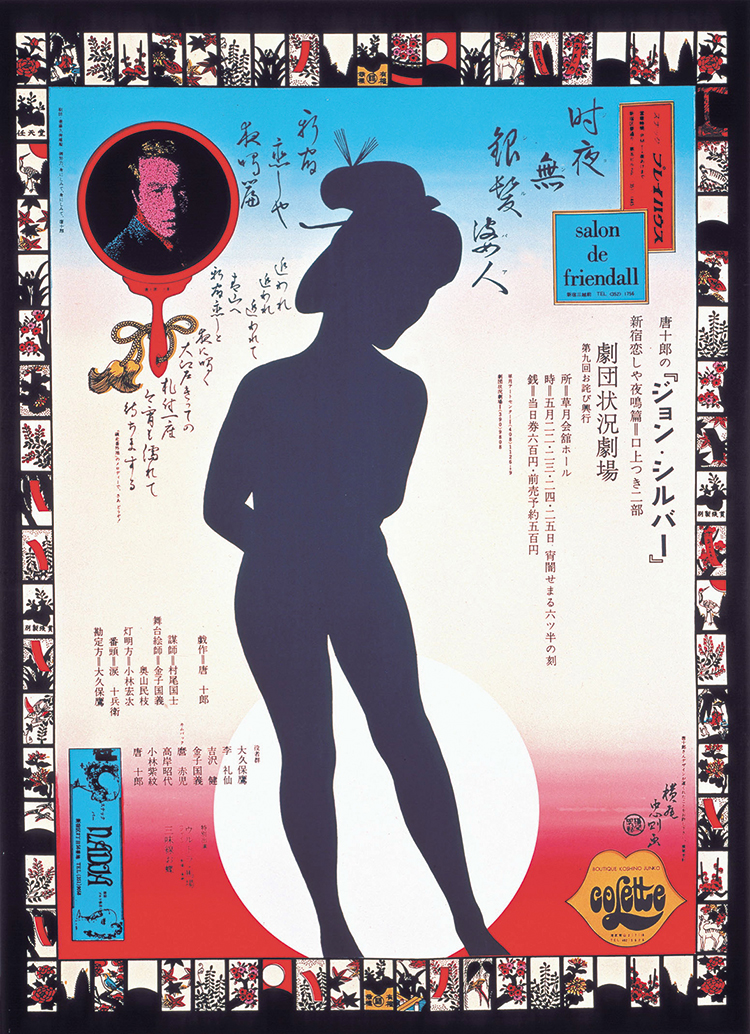

Poster of John Silver, play performed by The Situation Theatre led by Kara Juro. Designed by Yokoo Tadanori.

Andrews likes to point out Kara and Terayama’s different personalities and approaches to theatre. “There is a 2010 book by Steven C. Ridgely whose subtitle reads The Antiestablishment Art of Terayama Shuji. Obviously, Terayama was a central countercultural figure, but at the same time he was quite savvy in his dealing with the mainstream. On the one hand, you have Kara who in 1969 was arrested for doing a performance in West Shinjuku’s Central Park. Terayama, on the other hand, cleverly juggled underground and mainstream culture while cultivating this rebel image. His themes and practices were certainly avant-garde, but at the same time he needed some of the official institutions’ money and attention. After all, he later went on to have a rewarding relationship with Shibuya’s commercial Parco Theatre in the 1970s, at a time when he (like the other underground artists) had no support from the theatre establishment. You could say they fed off each other. He was even invited abroad by arty bourgeois festivals, while Kara visited refugee camps in the Middle East or went to Bangladesh, when these places were even more dangerous than now.”

Another important Shinjuku hotbed of activity was the Art Theatre Shinjuku Bunka, which was actually a cinema. “That’s true,” Andrews says, “but in the evenings, after the films were over, they started to organise theatrical performances as well.” The first stage performance in the Shinjuku Bunka was the Japanese premiere of Edward Albee’s The Zoo Story in 1963, followed by plays by Tennessee Williams, Samuel Becket, Harold Pinter, LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka), Jean Genet, etc. But the theatre also put on many plays by leading Japanese writers – not only Terayama and Kara but even Betsuyaku Minoru, Shimizu Kunio, and Mishima Yukio. Thus, despite its tiny stage, it quickly became one of Japan’s major venues for contemporary drama.

The 1970s saw a shift away from Shinjuku, and from Tokyo in general. This culminated in director Suzuki Tadashi moving his troupe, Waseda Shogekijo, from Tokyo toToga, a remote mountain village in Toyama Prefecture, in 1976. Suzuki went on to establish, in 1982, Japan’s first real international theatre festival.

G. S.