An administrative decision means a product that’s been around for more than 400 years risks disappearing.

Hatcho miso is aged for two years in kegs covered with a pile of stones.

Hatcho miso is aged for two years in kegs covered with a pile of stones.

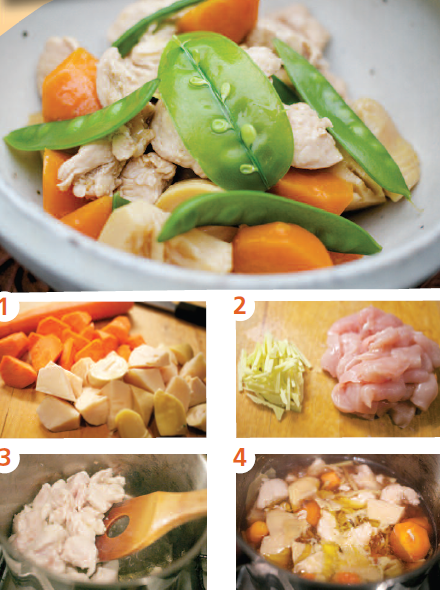

Like every region in Japan, which all have their own local miso, Aichi is renowned for its food seasoned with its own intensely flavoured red miso, notably Hatcho miso, which is famous for its particular method of production. Miso can be based on soya, salt and koji, a type of mushroom which encourages fermentation and is grown on a bed of rice or cooked wheat. But in the case of Hatcho miso, koji mushrooms are cultivated directly on soya beans, a technique that requires great skill and more time to ferment.

Maruya and Kakukyu are two small producers located a hatcho from one another (which equals 8 blocks or 870 metres and is where the name Hatcho miso is derived from). They are from Okazaki Castle, where the first Tokugawa shogun (military commander) was born and still follow the authentic method of producing Hatcho miso. The miso is allowed to age naturally for more than two years at an ambient temperature in cedar-wood kegs covered in stones in the form of a cone. This traditional method ensures that Hatcho miso is “the miso of kings”, and it’s all the more precious these days as some industrial manufacturers produce and place their miso on sale in just a matter of weeks. The mixture of umami, slight acidity, a touch of bitterness and low salt content adds a depth to dishes, which need not be confined to Japanese cuisine. It’s equally at home in many Western dishes; whether in stews or cakes, it adds a flavour similar to cocoa or salted butter caramel!

It’s become more than just a local product, and has been seized upon by Europeans who follow a macrobiotic diet and appreciate the traditional methods and organic ingredients used in its production. The miso made by these two producers can be found abroad, both in Europe and the united States, due to a contemporary phenomenon that allows local products to achieve international success thanks to their many aficionados.

But, at the moment, these products are going through a critical time: Japan’s Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries has taken them off the “GI” list (Geographical Indication system, equivalent to the AOC system for French wine), which protects distinctive regional brands. Aichi Prefecture’s miso cooperative, the largest in the region, has been designated in their place. Perhaps the government has done this because it wants to encourage mass exports of miso. However, this decision means that these two traditional makers of miso not only lose the right to use the name Hatcho for any of their new products but they also risk being unable to export their products to Europe, which could prove fatal for them. Shibata Kaori, an expert in the culture of cookery, emphasizes that there are similar cases in Europe, and proposes the adoption of his own system of two categories to protect local products, based on the strength of their connection with the region (PdO and PGI). For example, to distinguish balsamic vinegar made in the traditional way (PdO) from balsamic vinegar produced in the region (PGI).

The system that was originally brought in to protect the producers’ interests could, in the end, be used against them. This irony, characteristic of our modern times, must not be allowed to kill off a culinary tradition that has lasted for more than 400 years.

SEKIGUCHI RYÔKO

SOlIDARITY

MESSAGES OF SUPPORT, written in any language, can be addressed to the local producers online:

Maruya Hatchômiso : www.8miso.co.jp

Kakukyû : www.kakukyu.jp