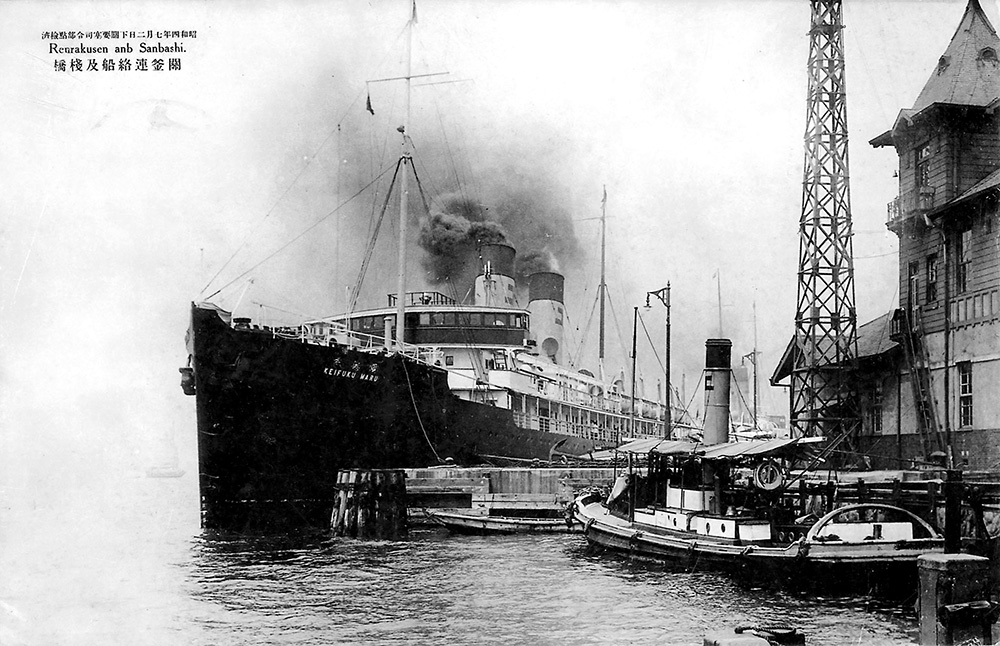

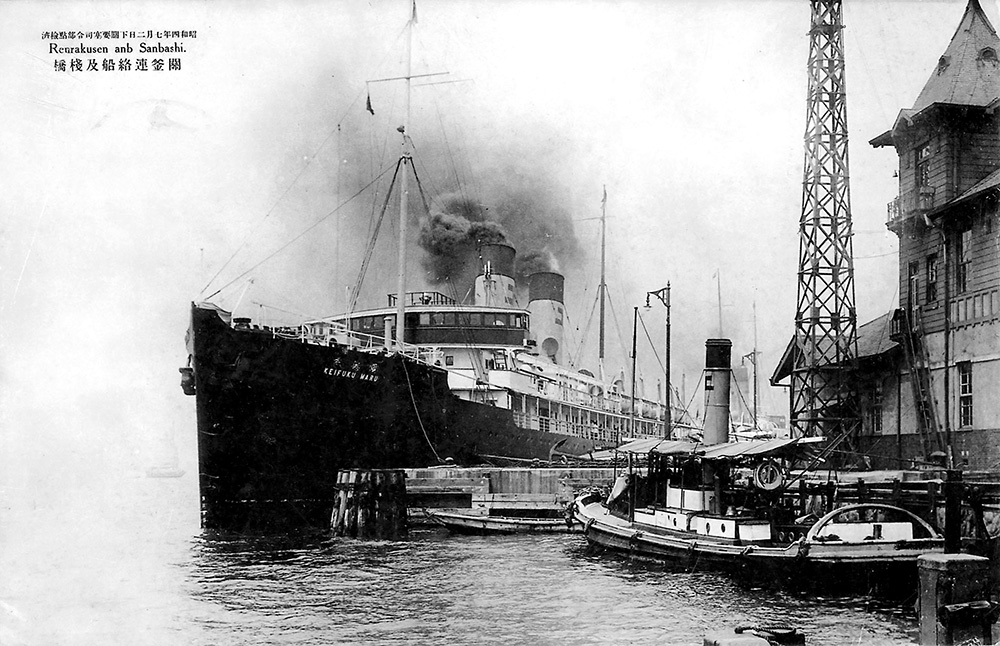

Since 1905, the port of Shimonoseki has been one of the main entry points for Koreans in search of a better life in the Archipelago./All Rights Reserved

To understand the reasons for the tensions, you need to be aware of the sometimes painful relations between the two countries.

During the 1980s and early 90s, many foreigners who came to Japan as tourists but wanted to stay longer than the three months granted to people without a proper visa resorted to the classic “Asian trip” trick: when their three-month period was about to expire they visited another Asian country for a few days then returned to Japan, thus getting an automatic three- month extension.

Many of them went to Shimonoseki, in Yamaguchi Prefecture, and from there took a ferry to Busan in South Korea. That route became so popular among expats and travellers that after a while the customs officers got wise to all that coming and going and started questioning people, even refusing them re-entry into Japan.

However, there was a time a century ago when the Busan-Shimonoseki ferry played a completely different role in the life of hundreds of thousands of people: it was one of the main routes taken by Korean immigrants to reach Japan.

Dating back to 1897, the Korean diaspora grew in volume after the country first became a protectorate, following the Japan-Korea Treaty of 1905. Later, in 1910, it was annexed to the Japanese Empire. The Busan-Shimonoseki ferry service started in 1905. It was always full and couldn’t keep up with the demand, leading the authorities to open additional routes to Osaka (1923) and Hakata (1943). From the late 1920s to the 1930s, between 80,000 and 150,000 Koreans came to Japan every year. The Busan maritime police were very strict and only people with enough money, able to speak Japanese, and with confirmation of employment were allowed to travel.

Even so, the number of Koreans entering Japan in 1930 reached 400,000. Many of those people left Korea as a direct result of intense economic exploitation, and the social and cultural dis- crimination to which they were subjected to in their own country. In 1910, for instance, there were 170,000 Japanese settlers in Korea (the largest single overseas-Japanese community at the time). The 1910 Land Ownership Survey promoted by the colonial authorities ended up favouring the settlers over local owners who had often only received traditional verbal agreements. As a result, the number of Japanese landowners soared (from 7% of all arable land in 1910 to 52.7% in 1932), whereas many Koreans lost their land overnight to become poor tenant farmers who had to pay over half their crop as rent. Then in 1918, a rice shortage in Japan prompted the government to issue the Plan for Increasing Rice Production, which in practical terms meant Korean land was used to provide rice for the Japanese, further worsening the local population’s living conditions.

Pachinko is a kind of vertical pinball game that the Japanese are crazy about. Its ball-making industry is predominately run by members of the Korean community in Japan.

However, on the other side of the Sea of Japan the economy was booming, and the factories that were mushrooming everywhere were hungry for cheap labour. Rumours spread in Korea about job opportunities and the promise of a better life, so people began their pilgrimage across the sea to Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya, Fukuoka, and all the way north to Hokkaido.

The Korean community in Japan was the object of constant discrimination in addition to being relegated to gruelling manual labour (levelling mountains, digging sewers, working in docks and shipyards) and dirty jobs the Japanese avoided like the plague (collecting rubbish, leatherwork, slaughterhouse work), while being paid less than their Japanese counterparts. In September 1923, things came to a head in the aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake when a few thousand of the 20,000 Koreans living in Tokyo and Yokohama were killed by mobs of vigilantes after falsely being accused of starting fires and poisoning wells. Their continued troubles notwithstanding, many Koreans moved to Japan all through the 1920s and 30s, having run out of ways to make a decent living in their home country. Still, leaving their families behind was far from easy. It’s not by coincidence that the top five songs among first-generation of Koreans in Japan in the 1930s were “Living Abroad”, “The Ferryboat Leaves”, “The Sorrow of the Wanderer”, “Tears of Mokpo” and “Sorrowful Serenade”.

In the meantime, things back home were going from bad to worse. Between 1936 and 1942, under Governor-General MINAMI Jiro, people in Korea were obliged to worship the Emperor and regularly attend Shinto shrine services. Even more importantly, they had to stop wearing traditional Korean clothes, use only the Japanese language and adopt Japanese-style names.

At the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, Japan established a comprehen sive mobilisation system that involved both the military and the economy. Forced labour – the issue that has mired relations between the two countries in recent months – began in the autumn of 1939 as so-called “company-directed recruitment” escalated through the Pacific War years, leading to 720,000 people being forcibly mobilised from Korea to Japan, South Sakhalin and the South Pacific, pushing the Korean community in Japan to over two million people.

About half of them worked in coal mines, and the rest in iron ore mines, on construction sites, in factories, ports and on farms. Anyone who protested was sent to prison camp, and in order to prevent people from deserting their work the companies paid the bulk of their wages into bank accounts that the workers could not access. Issues regarding unpaid wages, the abandonment of victims’ possessions as well as the separation of families in Sakhalin (when the island was invaded by the Soviet army and the Korean population was unable to return either to Korea or Japan) remain unresolved to this day, and they periodically contribute to an exacerbation of the already tense relations between the two governments. One of the main reasons why these issues have not been resolved once and for all is the different way the two countries view the past. South Korea, in particular, has always stated that the 1910 Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty, which marked the beginning of Japan’s colonial rule of Korea, was illegal from the start (some- thing the Japanese government has never acknowledged). This is both a basic tenet of their national ideology and the basis for the South Korean Supreme Court’s October 2018 ruling on forced labour.

Indeed, from the beginning of Japanese colonial rule, many Koreans opposed the political status quo, as confirmed by the Declaration of Korean Independence (8 February 1919) issued by 600 Korean students in Japan, and the March First Movement in the same year – an early uprising against Japan that was violently suppressed by the Japanese military. After the war, most Koreans hurried to get back home, but about 600,000 remained in Japan, again struggling against discrimination to come up with ways to survive and prosper. The game of pachinko (a sort of vertical pinball machine) was the start of a Korean niche business. It was first launched in Japan during the 1920s and reappeared soon after the end of the war. J-Koreans started joining the pachinko industry around 1947, and established a virtual monopoly of the popular gambling game until 1954, when the authorities banned automatic pachinko machines causing the number of parlours to dwindle from 50,000 to 9,000. Today, pachinko parlours may not be as popular as before but they are still ubiquitous, especially near railway stations, and they still represent the ceaseless efforts of Koreans in Japan to over- come social and economic adversities.

Currently around seven million Koreans are said to be living abroad, but the Korean community in Japan continues to have a special place in the country because of the historical circumstances that have shaped the lives of J- Koreans and the two countries during the last century.

J.D.

This article is based on a visit to the History Museum of J-Koreans in Tokyo. This museum was created in 2005 with the aim of collecting, organising and displaying materials and doc- uments relating to the history of Koreans living in Japan.

www.j-koreans.org (in Japanese and Korean)