SUZUKI Shin’ichi was 31 years old at the time of the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games.

As a privileged witness to the Olympic frenzy 56 years ago, Suzuki Shin’ichi shares his memories.

Waiting for the Tokyo Olympics reached fever pitch at the start of 1964 and didn’t let up until the end of the Games. media frenzy, in particular, got everybody involved, from hardbitten newshounds to highbrow intellectuals.

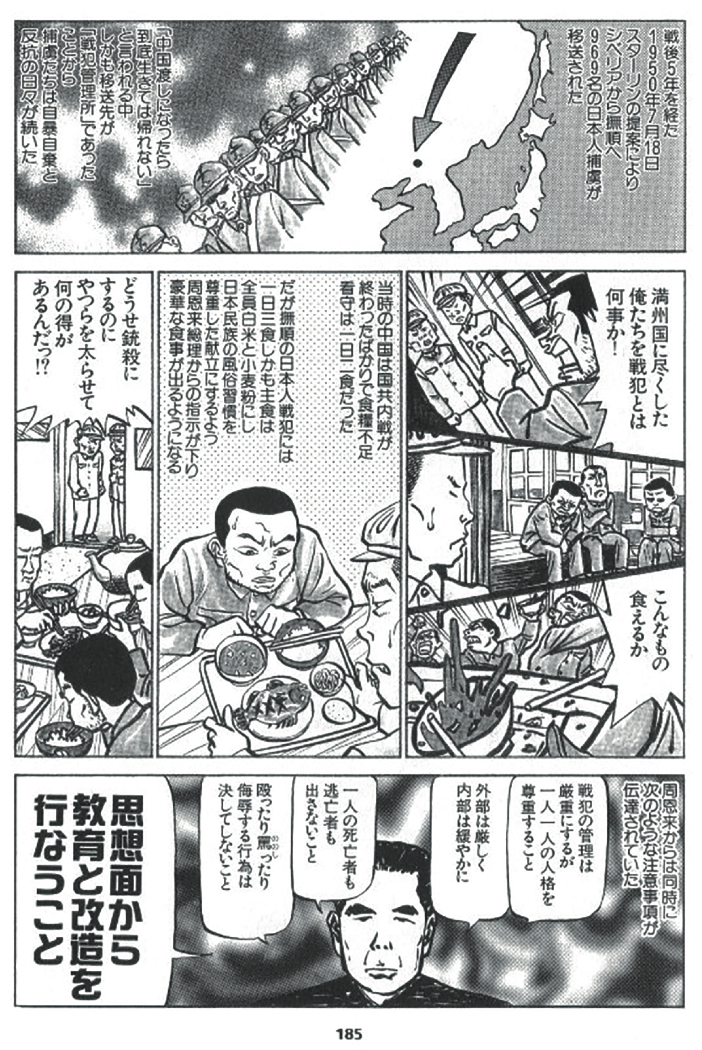

A number of famous authors such as MISHIMA yukio and Oe Kenzaburo for instance covered the event for national dailies and magazines. But not everybody saw the Games in a positive light. Indeed, several voices were quite critical of the Olympics, including ISHIKAWA Tatsuzo, the very first winner of the prestigious Akutagawa Prize. ISHIKAWA was famous for being independentminded and often contradicting State propaganda in his writings. In 1938, for example, Chuo Koron magazine sent ISHIKAWA to China to cover the war and the capture of Nanjing, and he produced such a brutally realistic novel Soldiers Alive [Ikiteiru Heitai, ed. University of Hawai’i Press) that his work was immediately banned by the authorities, and ISHIKAWAwas arrested together with his editor and three publishers for “causing disturbance to peace and order”.

Concerning the Olympiad, ISHIKAWA famously said: “These Games must have cost a fortune. I wonder why all the participating countries have endured such a financial sacrifice, just for the right to join a sporting event”. However ISHIKAWA’s opinion mellowed a little during the event. In the end he agreed that “war only leaves death and hatred in its wake, while sport has the power to inspire love and friendship even when you end up on the losing side”.

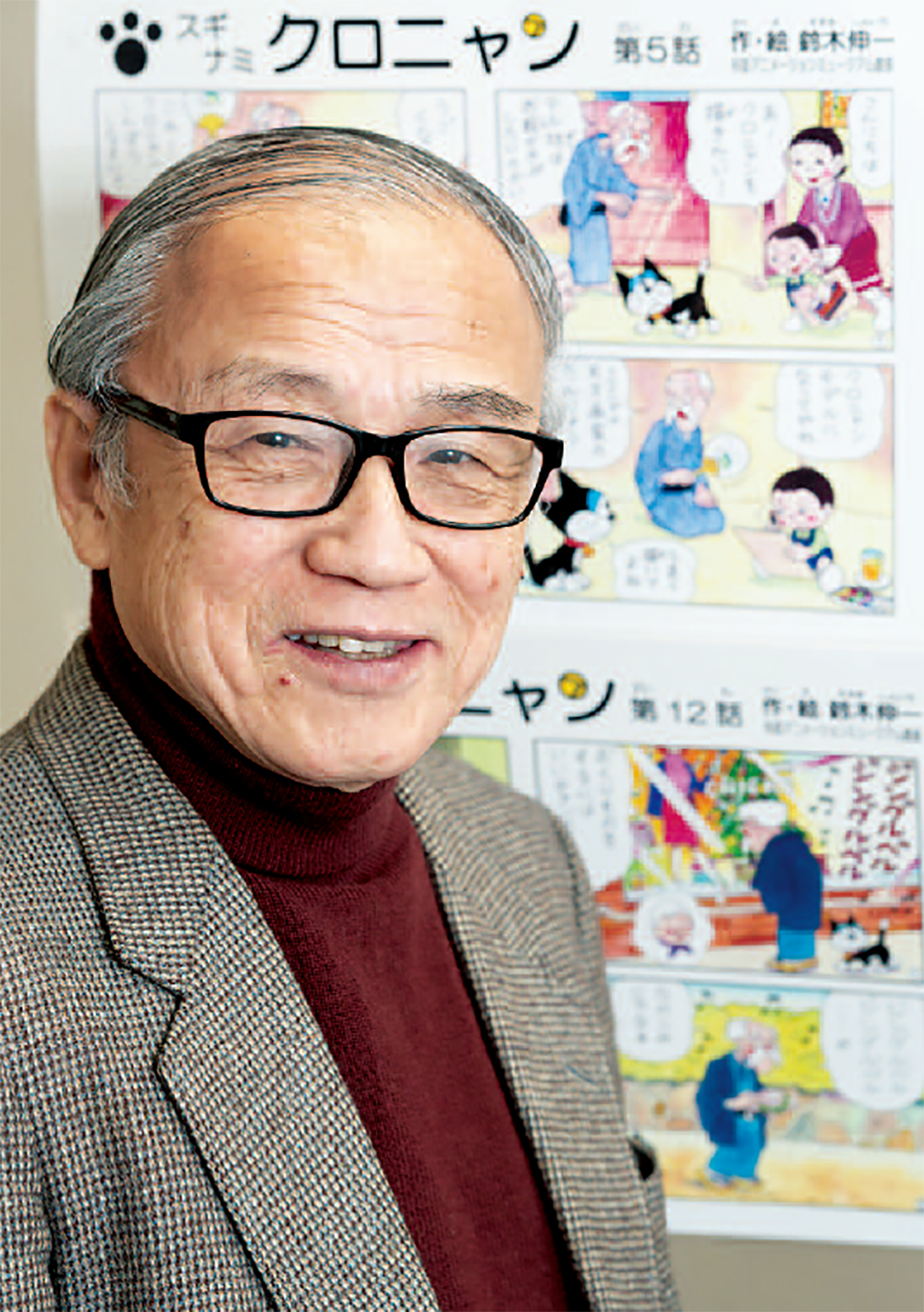

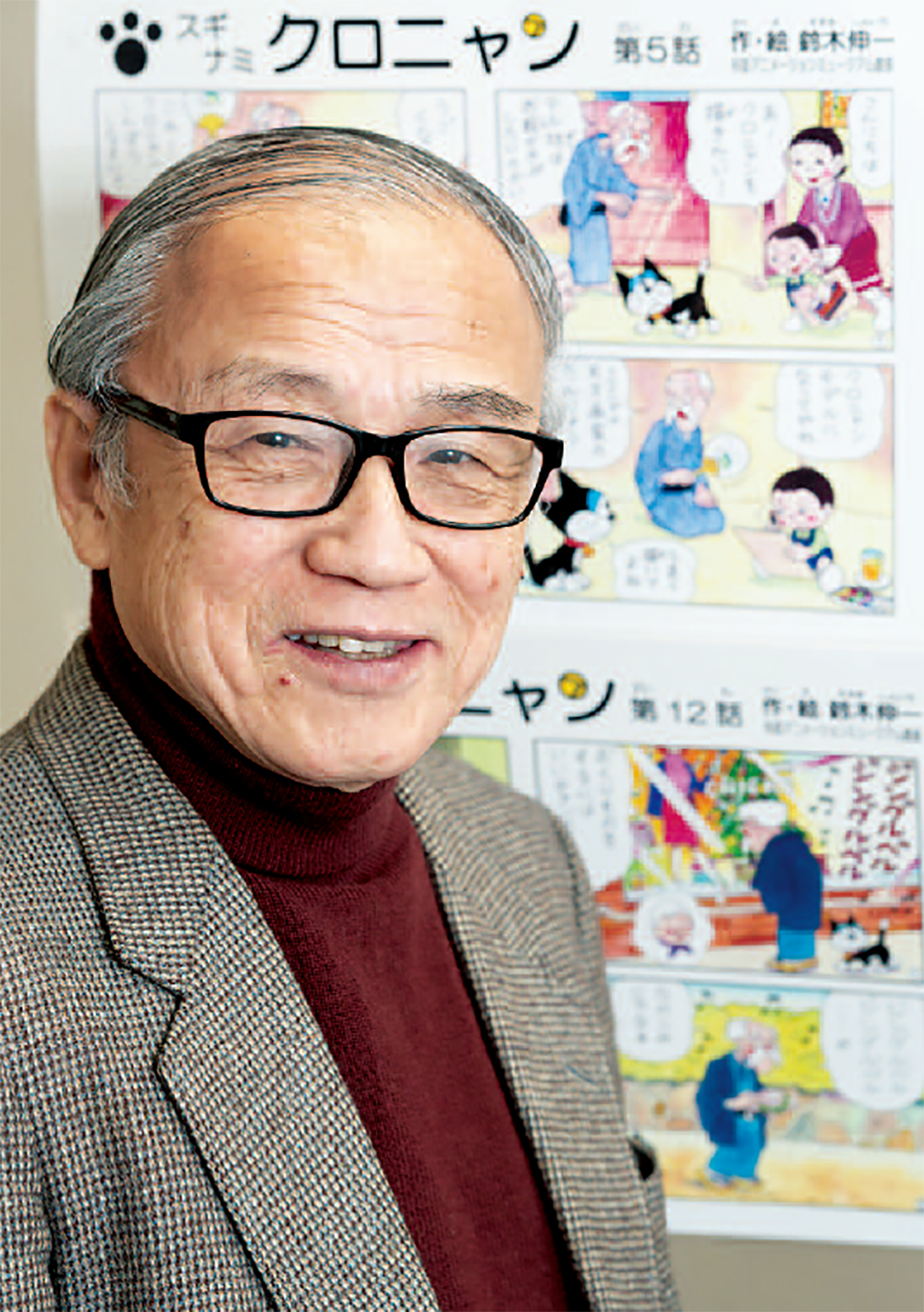

Even manga and anime creator SUZUKI Shin’ichi was swept along by the general enthusiasm. For the last 15 years, SUZUKI, 86, has been the director of the Suginami Animation museum in Tokyo (see Zoom Japan #77, December 2019), but in 1964 he was 31 and busy presiding over his small animation company, Studio Zero, and working for TeZUKAOsamu.

Born in Nagasaki in 1933, SUZUKI migrated with his family to manchuria when he was a child and only returned to Japan after the war, in 1946. “I became serious about drawing comics when I was in junior high school,” SUZUKI says. “editor KATOKen’ichi had started a new magazine called Manga Shonen, and people from all over Japan were invited to contribute. I sent many stories, and several of them were published. That’s when I started thinking that maybe I was good enough to become a professional comic artist.”

SUZUKI’s next step was moving to Tokyo in 1953. After spending three months with family friends, he got an invitation from TeRADAHiroo, a fellow Manga Shonen contributor, to move into Tokiwa-so, an apartment building where TeRADA was living with their childhood idol, TeZUKA Osamu, and two other young manga artists who signed their works as FUJIKO Fujio and would go on to become the world-famous creators of Doraemon.

SUZUKI kept making manga while working at a design studio, but when Manga Shonen went bankrupt, his main source of comic-related earnings dried up and he accepted an offer to join Otogi Productions, YOKOYAMA Ryuichi’s anime studio where he worked for about seven years before founding, together with FUJIKO Fujio and other manga artists, his own company, Studio Zero. “We didn’t make sports stories,” he says. “In order to make a successful supokon anime you need to be good at drawing muscles and other physical details. Our characters, in comparison, were much simpler. I was a big baseball fan though. I used to support the Nishitetsu Lions (today’s Seibu Lions) who won three Nippon Series in a row in the late 1950s.

Otogi Productions had a baseball team but we were so weak that we lost all the time. TeRADA Hiroo and FUJIKO Fujio sometimes joined us. ISHINOmORI didn’t have sports shoes so he wore geta (Japanese wooden clogs) (laughs). We were hopeless. Only TeRADA was good. He was quite big and had played at semi-professional level before becoming a manga artist. He even created a few baseball manga Sebango Zero [Uniform No. 0], Sportsman Kintarou well before the sports manga boom.”

In 1964 SUZUKI was living in Kamakura at a friend’s house, and would commute every day to Nakano where Studio Zero was located. “The Olympic torch relay passed near the studio building, along Ome Kaido, one of Tokyo’s main thoroughfares,” he says. “I saw both the Olympic torch runner and the jet planes when they flew over Tokyo and drew the Olympic rings in the sky on Opening Day.

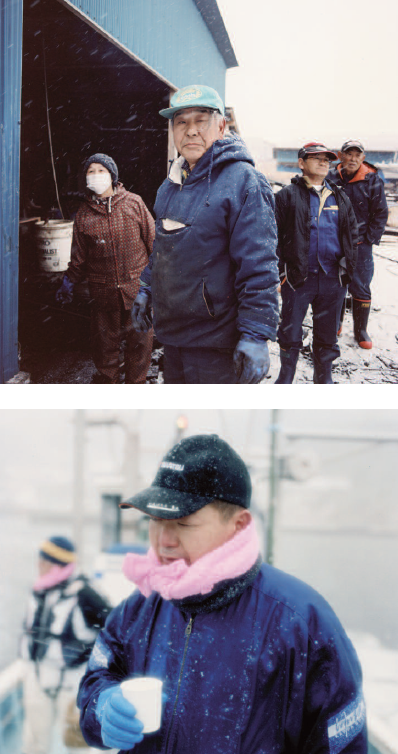

“Like most people, I was thrilled by the Olympic Games even though, except for baseball, I wasn’t a big sports fan. I think I only saw one live event – a volleyball game. more than sport itself, I was – well, everybody was – happy about the exciting times we were living in. Tokyo was changing day by day and was becoming the epitome of modernity. Not everything was good, of course. A lot of people were wearing masks, not because they had a cold or wanted to protect themselves from other people’s germs but because it was so dusty due to all the construction and public works going on around the city. The air was filthy, but at that time most people agreed that all those things were done for the greater good. We wanted progress.

After returning to Japan in 1946, and witnessing the destruction all around Nagasaki, I couldn’t be but hopeful about the future.”

During those days, most households bought a TV set in order to watch the Games. But the Games were featured everywhere. “I remember that many weekly and monthly magazines, like Manga O [manga King], included sport-related stories and children’s games devoted to the Olympics,” SUZUKI says. “One of the manga artists who featured the event best in their stories was HASeGAWA machiko. Her four-panel manga, Sazae-san, appeared daily in the Asahi newspaper, so she had more opportunity to include timely references to the news in her strips.

“There’s a story, for example, where Namihei, Sazae’s father, doesn’t feel well. The other family members make light of his problem, but become desperate when the TV set breaks down because they worry they’ll not be able to watch the Opening Ceremony. In this story, HASeGAWA echoes the opinions of those critics who thought that all the money spent on the Olympics could have been used for better purposes.

“In another strip, a drunk Namihei worries about the weather: as the constant rain may ruin tomorrow’s Opening Ceremony. Then he looks up into the night sky and sees lots of stars, but he’s disappointed when he realises it was only an American flag.”

Indeed, in HASeGAWA’s comic strips and other manga of that period there are oblique comments about the social conditions of the time, and how different people were affected and moved by the Games.

J. D.